Round table: Another Europe, More Europe

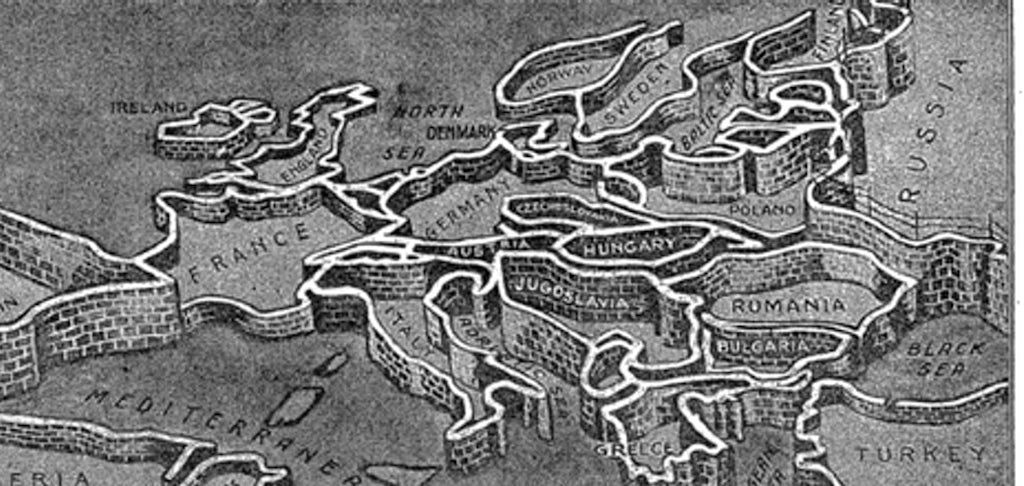

Imaginary walls in Europe (c) New York Times, 1926

Contributions by Flanders Arts Institute, European Culture Foundation, Bunker, Balkan Express & Budapest Observatory

Het eerste deel van dit artikel is enkel beschikbaar in het Engels. Onderaan kan je wel een kort verslag lezen in het Nederlands.

How can we collaborate differently within a changing Europe and from what set of values do you start out? What processes do you set up to understand one another’s context and to be open to artists and places that receive less attention internationally? From what vision on mutual solidarity? What financing mechanisms can support this approach? How can cultural diplomacy build bridges and stand under the sign of exchange?

Flanders Arts Institute organized a round-table discussion on 27th of February 2017 on artistic collaboration within Europe, tackling these different questions. About 70 participants attended the round table: artists, curators and programmers, organisations, cultural institutions and foundations and policy makers from Belgium, other European countries and the EU.

Another Europe: 15 years of European Culture Foundation-projects and bottom-up capacity building in the EU and its neighbouring countries

Philip Dietachmair (European Culture Foundation ECF) and Milica Ilic (ONDA) have a lot of experience with exchange projects that bet on prospection, capacity building, organisation development and intercultural collaboration. They edited together the book Another Europe (2015) which provides an overview of 15 years of ECF projects in Eastern Europe and the EU’s neighbouring countries. ECF looks beyond the EU borders, embracing the countries that touch the EU to the east and to the south, believing that our culture can be shared beyond the classical borders.

‘In the late 1990s we were pioneers’, Dietachmair explained, ‘but in the meantime, the EU has devoted some attention to culture in its foreign policy. You can see that as an effect of slow, bottom-up work by local initiatives in difficult circumstances’.

‘How did it happen? In the late 1990s a whole process was set up, although it wasn’t clear at the time what this process would look like. Via a call for projects, ECF traced a whole bundle of interesting initiatives in Europe’s neighbouring countries. When we saw the conditions in which people had to work, we focused heavily on capacity building via training programmes. The next step: you see that there are suddenly a lot of interesting initiatives in the region, which suddenly also start networking and working together. There was no cultural policy context, so then we focused on advocacy: these transnational networks of grass-roots initiatives have developed a lot of clout. Thanks to their reinforced position they can really weigh in on policy development.’

From the start, it has not been about the East learning from the West. It has been about developing a way of working that is really fully suited to the local circumstances.

Milica Illic

‘There is a red thread in all the projects that we supported’, says Milica Ilic. ‘To start with: they all come from the independent sector, not from public institutions. There is talk in the whole region of the ‘Great Divide’, the gap between the institutional scene (which is subsidised, and recognised by the state machinery) and the independent scene (very vulnerable, precarious, and without any long-term prospects of subsidisation). ECF-backed projects function fully independently. You then see a number of recurrent elements. To begin with there is the ambition to rethink “the system” and to develop radically new models to create and disseminate culture. There is also the freedom not to be limited in this by the existing practice in institutions, but to create new places to set up new institutions to give fundamental ideas a place. There is an interesting example in Zagreb, called Pogon. That is a place that allows you to step outside the binary thought of public versus private. In the book you can also read an interview with Marek Adamov on how they developed their work model, entirely suited to the needs and possibilities in a local environment. Adamov says that their work is less focused on developing artistic content themselves, but especially on creating a meeting space.’

‘That type of reflection can be very instructive for venues in the West. You not only reflect on what you programme, but especially on how you work. Your organisation must be in tune with the values you stand for. This is a red line in all the stories in the book. And it is also important for ECF. It is central to their capacity-building programmes. From the start, it has not been about the East learning from the West. It has been about developing a way of working that is really fully suited to the local circumstances, which can vary strongly. All projects in the book demand a deep understanding” of local situations.’

‘Another red thread in all stories is social engagement. It is important to be clear about how this works. It is not about lowering the bar artistically. In the West you often see a gap between artistic work and sociocultural work. In the South and East that distinction is a lot less clear. It is precisely in sociocultural environments that you find the work that is artistically most incisive. Artistic work is also heavily value-driven. That is why there is a lot of interest in connections with other value-bound sectors, such as environmentalism.’

‘Teo Celakoski, the intellectual force behind this process in Croatia, is someone who also inspired a lot of other initiatives in the Balkans. Marek Adamov is just as animated. His standpoint is that you can talk to everyone, conservative or progressive. There is always a shared interest, or a common idea as regards solutions. I agree with him that you need a dialogue with the institutional framework. At the same time I want to go further. The West should also engage in this dialogue, but no longer from a Eurocentric perspective, and with a more open spirit and greater appreciation for what is happening in the region.’

Debate

Chris Keulemans (CK): “The book Another Europe builds on the believe that art and culture are essential for democratic processes and intercultural dialogue in all European countries. The independent scene of artists and platforms have an impact on society being a change maker. This believe is highly contrasted with the Europe of today, in which these values are suddenly under pressure in all countries by populism and nationalism. What happened with fifteen years of capacity building in Eastern and Southern Europe?”

We proberen hier content te tonen van Vimeo.

Kunsten.be gebruikt minimale cookies. Om inhoud te zien die afkomstig is van een externe site, kan die site bijkomende cookies plaatsen. Door de inhoud te bekijken, aanvaard je deze externe cookies.

Lees meer over onze privacy policy.

Dessislava Dimova (DD): “The experience of the past 20 years has shown that it is difficult to function outside the existing institutions. It has become very difficult for the independent scene to continue working. It is good to see that there are initiatives that are being picked up and developed, but from our perspective it seems utopian. It would be interesting if you could reinforce the ties with the existing institutions. What is the experience in this regard?”

We proberen hier content te tonen van Vimeo.

Kunsten.be gebruikt minimale cookies. Om inhoud te zien die afkomstig is van een externe site, kan die site bijkomende cookies plaatsen. Door de inhoud te bekijken, aanvaard je deze externe cookies.

Lees meer over onze privacy policy.

Presentation of the independent art organization Bunker (Ljubljana, SLO)

Nevenka Koprivsek – artistic director of Bunker – presents the organization:

We proberen hier content te tonen van Vimeo.

Kunsten.be gebruikt minimale cookies. Om inhoud te zien die afkomstig is van een externe site, kan die site bijkomende cookies plaatsen. Door de inhoud te bekijken, aanvaard je deze externe cookies.

Lees meer over onze privacy policy.

Presentation of the Balkan Express Network

Balkan Express is a platform that connects people interested in collaboration in and with the Balkans involved in contemporary art and complementary socially engaged practices. Balkan Express is a platform for reflection on the new roles of contemporary art in a changing political and social environment. It builds new relations; encourages sharing and cooperation and contributes to the recognition of contemporary arts in the Balkans and wider.

Nevenka Koprivsek (NK): ‘What really boosted our development is the collaboration in the Balkans region. When we set up Balkan Express, we were already well aware of what was happening in Brussels or Paris. But we knew very little about what our neighbours in the region were doing. That is the reason why we set up the Balkan Express network. Balkan Express gathers partners from the region who want to collaborate transnationally around socially engaged artistic practices. By now it has grown into something really big, but it still works very informally. In June we are having a meeting in Ljubljana – to which, by the way, you are cordially invited.’

Milica Illic (MI): ‘In order to contextualise the origin of Balkan Express, you need to have a good grasp of the working conditions in the independent sector in the region. There is a lot of precariousness, and so people are constantly busy creating the conditions of possibility for a next project. You really dash from one to the next. It is precisely for this reason that the network has always tried to create the conditions (time and space) for a fundamental reflection about projects and work conditions. That’s the point: to establish moments to talk about common ground, and to create openings for something new.’

NK: ‘Today there is talk of exhaustion. The conditions have become really difficult. Our staff has decreased by a quarter, and we have to work harder. We really are on the edge of precariousness and exhaustion. We have some experience with this. But today the transfer of experience is important – “how to teach fighting”. We have to pass on to a new generation our competences and skills in terms of survival.’

MI: ‘There is a lack of understanding and knowledge about who does what. But even more so, there are a lot of deeply rooted prejudices with regard to the region. We really have to name them, because they stand in the way of genuine collaboration. The work is always too this, or not enough that: too exotic, or not exotic enough, or not contemporary enough. Nothing is ever good enough. There are a lot of prejudices from the centre of power.’

Philip Dietachmair (PD): ‘That’s right, but that centre of power is also changing. That is something we are learning through our experiences in the context of the Tandem programmes. Work conditions in the north of England are just as precarious as those in the Balkans. The collaboration today happens on a more equal footing. That is precisely why interest is growing in exchange about possible innovative work models.’

Debate

Felix De Clerck (Kunstenpunt/Flanders Arts Institute): ‘What is meaningful collaboration?’

We proberen hier content te tonen van Vimeo.

Kunsten.be gebruikt minimale cookies. Om inhoud te zien die afkomstig is van een externe site, kan die site bijkomende cookies plaatsen. Door de inhoud te bekijken, aanvaard je deze externe cookies.

Lees meer over onze privacy policy.

Question by Chris Keulemans on misunderstanding between programmers/curators in the West and artistic work which is produced in Balkans and Eastern Europe:

We proberen hier content te tonen van Vimeo.

Kunsten.be gebruikt minimale cookies. Om inhoud te zien die afkomstig is van een externe site, kan die site bijkomende cookies plaatsen. Door de inhoud te bekijken, aanvaard je deze externe cookies.

Lees meer over onze privacy policy.

Question on how to end prejudice and the role of intermediary organizations like ONDA:

We proberen hier content te tonen van Vimeo.

Kunsten.be gebruikt minimale cookies. Om inhoud te zien die afkomstig is van een externe site, kan die site bijkomende cookies plaatsen. Door de inhoud te bekijken, aanvaard je deze externe cookies.

Lees meer over onze privacy policy.

Presentation of The Budapest Observatory

Peter Inkei: ‘The Budapest Observatory was founded 18 years ago. We are an observatory, which is to say that we observe. We observe Eastern Europe. By that we mean the former communist countries. Is this sufficient as a communal identity? What do we have in common? What is our shared heritage? In the beginning, such a thing as an ‘independent artist’ was new to us. Besides: most of our countries are nation states which, when they left the Ottoman Empire, became embroiled in a complex process of nation-building. In one way or another, that undigested idea of nation-building is still relevant for our countries. Something else: lagging behind. There is this idea that we are less successful than the West, that we are lagging behind. Not only economically, but in general. Only a select elite, which was also somewhat isolated, the urban middle class, looked ahead. Their relation with the lower classes is then again typical. It is the opposite of what Dickens wrote about nineteenth-century England. When you read Dickens, you see great respect for the working class. They are called Mister or Miss. In our corner of the world, people look down on the working class. At the same time there is a sort of folk exoticism. It is a source of pride, but it is also a danger. You run the risk of conforming to a presupposed idea about tradition.’

What do we have in common? What is our shared heritage?

‘We have a project going at the Budapest Observatory called the Eurobarometer. It shows that Eastern European countries have an attitude to art and culture that is different from the West. For instance, people go to the cinema a lot less than in the West. If it is about what the EU means to you, then there are only a few people in the East who saw cultural diversity as the binding agent of the European project. How we should explain that is unclear. But what is clear is that attitudes differ in the East and the West of Europe.’

‘Perhaps it has to do with the different forms of idealism that were propagated in the East and the West after World War II. The values were different, but in both regions you can talk of hierarchical paternalism. Everywhere the leaders knew what was good for the people, and the population accepted that. Today things have changed completely. There are so many different lifestyles and subcultures, and there is the power of social media. As a result, that kind of top-down influencing is now outdated. You see what happens when a leader emerges that simply agrees with the people – the ‘deplorables’, in the words of Hillary Clinton – in their primary feelings. Certainly in the East there is a vast breeding ground for frustration, for jealousy. The idea that going back to a former national glory or to imaginary communities can be an answer to social challenges is the stuff of dreams or hopes.’

We have a project going at the Budapest Observatory called the Eurobarometer. It shows that Eastern European countries have an attitude to art and culture that is different from the West.

Another project of the Budapest Observatory is the Cultural Policy Barometer: ‘We collected 27 statements about art and culture, about what the most acute issues are at present, and asked cultural experts what they find important and what bothers them. There are significant differences between the answers from the East and the West. Colleagues from the West pay more attention to the social dimension of art and culture. In the West, the social meaning of art was evoked more often as an important challenge. Why was this acknowledged less in the East? Perhaps because work conditions are more precarious than in the West? Another issue where differences were more pronounced: for Western respondents, the decreasing local financing of culture was really a very big challenge. In the East this was felt less as a problem. The biggest problem of the Eastern European respondents was then again: the all too direct interference of policy-makers in subsidising. There was widespread agreement in one area: that there is not enough interest among policy-makers for art and culture.’

‘A lot of people see government spending on the arts as an important indicator of the flourishing of culture in a country. But that’s not true. In Hungary, a lot of money is still spent on culture. What matters is how that money is spent. The age-old dilemma – is the value of art intrinsic or instrumental? – has perhaps become obsolete. Art is always instrumental: it prepares us all to deal with the legacies from the past, to handle a changing world. We have to think about Europe as a metaphor, as a symbol. Not for institutions, but as a symbol for liberal democracy. We have to propagate that as a value, so that the partners in the cultural field can connect to that.’

A lot of people see government spending on the arts as an important indicator of the flourishing of culture in a country. But that’s not true. In Hungary, a lot of money is still spent on culture. What matters is how that money is spent.

About the contributors

Moderator Chris Keulemans

The debate is moderated by Chris Keulemans (Tunis, 1960) who was founder and artistic director of the Tolhuistuin until 2014. He grew up, among other places, in Baghdad, Iraq. In 1984, he founded the literary bookshop Perdu in Amsterdam. During the nineties, he worked at De Balie, Centre for Culture and Politics in Amsterdam, first as a curator, later as director.

Keulemans has published books, fiction and nonfiction, and has published numerous articles on art, social movements, migration, music, cinema and war for national newspapers. He traveled extensively to study art after crisis in cities such as Beirut, Jakarta, Algiers, Prishtina, Sarajevo, Tirana, New York, Sofia, New Orleans, Belgrade and Ramallah, where he visited many talented artists.

Philip Dietachmair

Philipp Dietachmair is Programme Manager with the European Cultural Foundation (ECF) in Amsterdam. Responsible for the foundation’s EU Neighbourhood Programme and Tandem Cultural Managers Exchange. He develops and manages long-term cultural policy- and capacity development initiatives for the cultural sector in Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Turkey, the South-East Mediterranean, Russia and the Western Balkans. From 1999 to 2001 he coordinated higher education development projects and organized cultural events in Sarajevo, Bosnia–Herzegovina for World University Service (WUS) Austria. Next to his work for ECF Philipp Dietachmair did PhD research studies in Cultural Entrepreneurship at the University of Utrecht.

Milica Ilic

Milica Ilic is part of the pool of in-house experts of the French office for contemporary performing arts circulation (ONDA). She is companying and advising French performing arts professionals in the circulation of contemporary performing arts work and encouraging the internationalisation of the French performing arts scene. She is developing and implementing Onda’s international projects and international partnership development. Milica Illic is author and co-author of several research studies in particular within the field of international cultural cooperation and arts and culture in South-East Europe and freelance coordinator of international and cross-cultural projects. She is collaborator to international cultural organisations and European networks managing subsidy applications, programme evaluations, strategic planning and project development. From 2006 till 2014, Milica Illic was head of communication and administration of IETM.

Nevenka Koprivsek

Nevenka Koprivsek was trained at Ecole Internationale de Theatre Jacques Lecoq. She started her professional career as actress than theatre director. She was artistic of Glej theatre 1989 until 1997, when she has established a new independent organization BUNKER and with it Mladi Levi International Festival and since then acted as the company’s artistic director. Since 2004 Bunker is also in charge of Stara elektrarna, an old power plant converted into performing arts center.

Nevenka was involved or co-founder of many international networks and exchange projects. Occasionally she is writing, lecturing and advising on different issues of programming and cultural policy. She is also certified practitioner and teacher of Feldenkrais method of awareness through movement.

In 2003, the City of Ljubljana gave Nevenka Koprivšek a major municipal award for special achievements in culture and in 2011 she has been honored by the Government of France as a Chevalier and in 2015 as Officier d’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

Footage shot by Pieter Deprez

Een verslag door Joris Janssen

Inleiding (Dirk De Wit, Kunstenpunt)

Als maatschappelijk en cultureel project zit Europa in een diepe crisis. Natiestaten plooien terug op zichzelf. De maatschappelijke meerwaarde van internationale solidariteit en samenwerking staat meer dan ooit ter discussie. Zeker voor de kunsten is de crisis urgent.

Het Europese cultuurbeleid, dat de laatste jaren vooral een economisch project leek, biedt voorlopig geen wervend alternatief voor het snel oprukkende cultuurpopulisme. Ook de integratie van nieuwe leden binnen de Europese Unie met andere geschiedenissen en sociaaleconomische realiteiten loopt minder vlot dan verwacht.

Hoe kunnen kunstenaars en organisaties uit Vlaanderen en Brussel zich in deze turbulente tijden verhouden tot deze crisis van de Europese gedachte? Kunstenaars en organisaties uit Vlaanderen en Brussel werken doorgaans niet zo frequent samen met spelers uit de Balkan of landen die grenzen aan de Unie. Onze marktlogica drijft ons naar andere regio’s en continenten. Nochtans is het in het veranderende tijdsklimaat meer dan ooit aan de orde om de connectie op te zoeken met het Zuiden en het Oosten. Niet alleen om de turbulente sociale, culturele en politieke ontwikkelingen binnen de Europese ruimte beter te leren begrijpen, maar ook omdat in het zeer actieve maatschappelijk betrokken artistieke landschap in deze regio’s de laatste vijftien jaar interessante en vernieuwende antwoorden in ontwikkeling zijn op vragen waar kunstenaars en organisaties in Vlaanderen en Brussel steeds meer mee te kampen hebben.

Hoe kunnen we anders samenwerken binnen een veranderend Europa? Vanuit welk waardenkader vertrek je, vanuit welke visie op onderlinge solidariteit? Welke processen installeer je om elkaars context te begrijpen en open te staan voor kunstenaars en plekken die internationaal minder worden gespot? Welke financieringsmechanismen kunnen deze demarche ondersteunen? Hoe kan culturele diplomatie bruggen bouwen en in het teken staan van uitwisseling (en niet alleen van promotie of nation branding)?

Another Europe: vijftien jaar bottom-up capacity building in de buurlanden van Europa

Philip Dietachmair (European Culture Foundation) en Milica Ilic (ONDA) lichten Another Europe toe, een boek met documentatie van 15-jarig proces bij European Culture Foundation, dat hiermee inzet op de ondersteuning van en advocacy omtrent grass-roots initiatieven in het Zuiden en Oosten van Europa. ‘Einde jaren 1990 waren we pioniers’, lichtte Dietachmair toe, ‘maar intussen is er aandacht bij EU voor cultuur in buitenlandbeleid. Dit kun je zien als een effect van langzaam, bottom-up werken door lokale initiatieven in moeilijke omstandigheden.’

‘Hoe is het gegaan? Einde jaren ’90 is een heel proces opgestart, zonder dat het toen al duidelijk was hoe dit proces er zou uitzien. Via een call for projects kwam ECF heel wat interessante initiatieven in de buurlanden van Europa op het spoor. Toen we zagen in welke omstandigheden de mensen moesten werken, zetten we sterk in op capacity building via trainingsprogramma’s. De volgende stap: je ziet dat er plots heel wat interessante initiatieven zijn in de regio, die plots ook beginnen te netwerken en samen te werken. Er is geen cultuurbeleidscontext, dus vervolgens zetten we in op advocacy: deze transnationale netwerken van grass-roots initiatieven zijn echt heel slagkrachtig geworden. Door hun versterkte positie kunnen ze echt gaan wegen op de ontwikkeling van het beleid.’

‘Er is een rode draad in alle projecten die we ondersteunden’, zegt Milica Ilic. ‘Om te beginnen: ze komen allemaal uit de independent sector, niet uit de publieke instituties. In de hele regio is er sprake van the “Great Divide” — de kloof tussen de institutionele scene (die gesubsidieerd is, en erkend door het staatsapparaat) en de onafhankelijke scene (heel kwetsbaar, precair, en zonder langetermijnperspectief op subsidiëring). De door ECF ondersteunde projecten functioneren volstrekt onafhankelijk. Je ziet dan een aantal elementen terugkeren. Om te beginnen is er een grote ambitie om ‘het systeem’ te herdenken en radicaal nieuwe modellen te ontwikkelen om cultuur te creëeren en te spreiden. Er is ook de vrijheid om zich daarbij niet te laten beperken door de bestaande praktijk in instellingen, maar om nieuwe plekken te creëeren om nieuwe instituties op te richten om fundementele ideeën een plek te geven. In Zagreb is er een interessant voorbeeld, Pogon. Dit is een plek die je toestaat om uit het binaire denken over het publieke versus het private te stappen. In het boek lees je ook een interview met Marek Adamov, over hoe ze hun werkmodel hebben ontwikkeld, helemaal aangepast aan de noden en mogelijkheden in een lokale omgeving. Adamov geeft aan dat hun werk daar er minder op gericht is om zelf artistieke inhoud te ontwikkelen, maar vooral om een ontmoetingsplek te creëren.’

‘Dit soort van reflecties kan heel leerrijk voor venues in het Westen. Je gaat niet alleen denken over wat je programmeert, maar vooral ook over hoe je werkt. Je organisatie moet in tune zijn met de waarden waarvoor je staat. Dit is een rode lijn in alle verhalen in het boek. En het is ook belangrijk voor ECF. Het staat centraal in al hun capacity building programma’s. Sinds het begin gaat het er niet om dat Oost moet leren van West. Het gaat er wel om een manier van werken te ontwikkelen die echt helemaal aangepast is aan de lokale omstandigheden, die sterk kunnen verschillen. Alle projecten in het boek vragen om een ‘deep understanding’ van lokale situaties.’

‘Nog een rode lijn in alle verhalen is sociaal engagement. Het is belangrijk om duidelijk te zijn omtrent hoe dit werkt. Het gaat er niet om de lat artistiek lager te leggen. In het Westen zie je vaak een kloof tussen artistiek werk en sociaal-cultureel werk. In het Zuiden en Oosten is dat onderscheid veel minder duidelijk. Precies in sociaal-culturele omgevingen vind je het artistiekst scherpste werk. Ook het artistieke werk is sterk waardegedreven. Om die reden vind je heel wat interesse in connecties met andere waardegewonden sectoren, bijvoorbeeld milieu-activisme.’

Chris Keulemans: ECF heeft echt een neus voor interessante initiatieven in de independent kunstensector, toen al. Kijken we naar de situatie in deze landen vandaag, dan zie je bijna zonder uitzondering dat er in deze landen rechtse, populistische, nationalistische regeringen zijn verkozen die vijandig zijn aan de kunsten en de waarden die de door ECF ondersteunde projecten hoog in het vaandel dragen. Hoe kijken jullie daarnaar?

PD: ‘In het boek wordt niet veel gesproken over vijandige regimes. Vooral ook omdat we er echt voor kiezen in dit soort van omstandigheden te werken en we het boek daar ook willen gebruiken. Maar het klopt: het perspectief is niet vrolijk. Tegelijk is het ook bemoedigend om te zien wat er bottom-up gebeurt, bijvoorbeeld in kleine dorpen in Wit-Rusland. Voor vele mensen is dit soort van projecten een venster op Europa. Vandaag moet je hopen dat dit soort van projecten in de underground, overleeft. Maar tegelijk is het nodig om op lange termijn te denken. Castells spreekt over netwerken van hoop. Het is belangrijk om daar ook vandaag op in te zetten.’

CK: Kunnen dit soort van initiatieven een inspiratie voor initiatieven hier, in snel veranderende omstandigheden ook bij ons?

Milica Ilic: ‘Je moet een beetje oppassen met veralgemeningen. Je hebt precariteit niet nodig om innovatief te zijn. Tegelijk ben ik wel optimistischer dan Philip. Je moet naar deze initiatieven kijken vanuit een globaal perspectief. Misschien gaat inderdaad alles overal de verkeerde kant op, ook in Westerse landen waar een grote culturele traditie bestaat. Als het daar fout gaat, kan het plots erg fout gaan. In die zin zijn de initiatieven in de buurlanden van Europa erg inspirerend. Niet enkel diegene in dit boek, maar ook andere netwerken en initiatieven. Als je nadenkt over radicale verandering, als je echt wil herdenken hoe we werken, ook de waardenkaders, dan denk ik dat die verandering zou kunnen komen van de marge.’

De ervaring van de laatste 20 jaar laat zien dat het moeilijk is om buiten de bestaande instellingen te functioneren. Het is erg moeilijk geworden voor de independent scene om verder te werken. Het is goed om te zien dat er initiatieven zijn die opgepikt en versterkt worden, maar vanuit onze context lijkt dit utopisch. Het zou wel interessant zijn mochten jullie de banden met de bestaande instellingen kunnen versterken. Wat is de ervaring op dit vlak?

PD: ‘Er is een beperkte ervaring terzake. Die komt in ons geval steeds voort uit de wens van onafhankelijke instellingen om te connecteren met bestaande publieke instellingen. Bivoorbeeld in Moldova hebben we de independent scene in contact gebracht met administraties op gemeentelijk en nationaal niveau. Dit is echter redelijk uitzonderlijk. Het zou meer moeten gebeuren. Maar er is zeker een interesse om te institutionaliseren. Het eerder vermelde Pogon is een interessant voorbeeld. Men heeft een bestuursmodel ontwikkeld dat een samenwerkingsverband is tussen de onafhankelijke sector en de stedelijke overheid.

We werken nu aan een boek dat precies dit proces van institutionalisering beschrijft. Het is allemaal begonnen met initiatieven in Zagreb die ontstonden vanuit een netwerk van mediakunstenaars, maar ze zijn daar nu bezig met de oprichting van een politieke partij. (Philip Dietachmair)

MI. ‘Teo Celakoski, de intellectuele kracht achter dit proces in Kroatië, is iemand die ook heel wat andere initiatieven in de Balkan inspireerde. Marek Adamov is even bevlogen. Zijn standpunt is dat je met iedereen kunt praten, conservatief of progressief. Er is altijd een gedeelde interesse, of een gezamenlijk idee wat oplossingen betreft. Ik ben het met hem eens dat je een dialoog nodig hebt met het institutionele kader. Tegelijk wil ik verder gaan. Het Westen zou ook in deze dialoog moeten stappen, maar niet meer vanuit een eurocentrisch perspectief, en met een meer open geest en waardering voor wat er in de regio gebeurt.’

De situatie in Polen

Marta Keil kon wegens ziekte niet aanwezig zijn, maar stuurde een boeiende tekst in die binnenkort online komt, na redactie. Ze spreekt over de situatie in Polen, waar censuur vandaag realiteit is en ook internationaal werken niet meer als een waarde wordt gezien. Maar hoe kijk je dan naar instellingen? Aan de ene kant is het in zo’n context belangrijk dat we kunstinstellingen beschermen. Tegelijk moet je ook kritisch kijken naar de manier waarop die instellingen functioneren. Je kunt wel instellingen willen die kritisch reflecteren over de condities van onze democratie. Maar tegelijkertijd passen ze die principes niet altijd toe in de manier waarop ze werken. Welke mogelijkheden creëer je als je nadenkt over onze kunstinstellingen als een politiek instrument?

Jarenlange eerstehandservaring in Slovenië

Nevenka Koprivsek sprak over Bunker, een intusse legendarische plek voor creatie, presentatie, residentie in Ljubljana. ‘Tussen Oost en West delen we een aantal besognes: de polarisering van onze samenleving, de toenemende ongelijkheid, oprukkend nationalisme… Misschien is Slovenië ook wel een plek tussenin verschillende regio’s in Europa, of tussen verschillende situaties die we beschrijven in Oost en West. We kunnen best jaloers zijn op de situatie in Vlaanderen. Maar vergeleken met pakweg Italie is de situatie bij ons rooskleurig. Het is dus maar waar je je positioneert.’

‘Toen ik Bunker opstartte, keek ik sterk naar het Vlaamse model. Toen ik de kans kreeg om artistiek directeur te worden van een theater, was dit interessant. Ik deed het acht jaar. Maar ik startte te begrijpen dat je om transnationaal te werken, vooral de juiste lokale omstandigheden moet creëeren. Precies om deze omstandigheden te creëeren, startte ik Bunker. Mladi Levi, ons internationale festival, is misschien het meest zichtbaar. Vandaag werken we in een elektriciteitscentrale die we ombouwden tot een theater.’

‘Het was destijds van in het begin de bedoeling om internationaal werk te tonen. We hadden geen presentatieplekken, dus we waren op zoek naar een eigen ruimte. In die tijden was er een vitale lokale scene. We lieten door de stad een studie bestellen omtrent plekken die eventueel omgebouwd konden worden tot artistieke presentatieplekken. Vandaag zijn er zeven van die plekken ontwikkeld en in gebruik. Dit was een heel langzaam proces op het vlak van lobbying. We werkten heel nauw samen met de stedelijke administratie. We schreven de teksten voor de calls waarop we vervolgens zelf intekenden. Het werk is succesvol, maar ook heel kwetsbaar. Het kan zo teruggedraaid geworden.’

‘Onze manier van werken veranderde drastisch. Voor een bepaald project deden we sterk onderzoek naar opvattingen binnen de lokale gemeenschap over kunst en cultuur. Dat deed ons anders nadenken over hoe je werkt met anderen. Nu zetten we heel veel projecten op met scholen, verenigingen… Hoe kunst en cultuur lokaal functioneren, is erg belangrijk. Bijvoorbeeld zijn er veel experimenten met cultuureducatie. Dat is echt tweerichtingsverkeer. Werken met adolescenten doet je anders kijken naar je eigen project. Ook dat is leren door cultuur. Openstaan voor impulsen uit de gemeenschap is belangrijk. Hoe je kunt openstaan voor verandering? Als we meer willen veranderen is het soms nodig om minder te doen. En meer tijd en ruimte te nemen om zonder agenda samen te komen en de zaak te herdenken. In het kader van ons festival vinden we het erg belangrijk om die ruimte te creëeren.’’

Balkan Express: tijd en ruimte voor fundamentele reflectie

NK. ‘Wat onze ontwikkeling echt voortgestuwd heeft, is het samenwerken in de Balkanregio. Toen we met Balkan Express startten, wisten we wel goed wat er gebeurde in Brussel of Parijs. Maar we wisten heel weinig over waar onze buren in de regio mee bezig waren. Om die reden startten we dus het Balkan Express netwerk op. Balkan Express verzamelt partners uit de regio die transnationaal willen samenwerken omtrent sociaal geëngageerde artistieke praktijken. Dat is intussen erg groot geworden, maar het werkt nog erg informeel. In juni hebben we samen met Kunstenpunt een meeting in Ljubljana, waarop u overigens van harte uitgenodigd bent.’

MI. ‘Om het ontstaan van Balkan Express te kaderen, is een goed begrip nodig over de werkcondities in de onafhankelijke sector in de regio. Er is een grote precariteit, waardoor mensen de hele tijd bezig zijn om de mogelijkheidsvoorwaarden te creëren voor een volgend project. Je holt er echt van project naar project. Precies om die reden heeft het netwerk steeds geprobeerd om de condities (tijd en ruimte) te scheppen voor een fundamentele reflectie over projecten en werkomstandigheden. Dat is het punt: momenten creëren om te spreken over gemeenschappelijke grond, en openingen te creëren voor iets nieuws.

NK. ‘Er is vandaag sprake van uitputting. De omstandigheden zijn erg moeilijk geworden. Onze staf is een kwart kleiner geworden, en we moeten harder werken. We zitten echt op het randje van precariteit en uitputting. Daar hebben we wel ervaring mee. Maar vandaag is de overdracht van ervaring belangrijk, ‘how to teach fighting’. We moeten onze competenties en skills op het vlak van overleven doorgeven aan een nieuwe generatie.’

MI. ‘Er is een gebrek aan begrip en kennis over wie wat doet. Maar nog sterker: er zijn heel sterke vooroordelen ten opzichte van de regio. Die moeten we echt benoemen en staat echte samenwerking in de weg. Het werk is altijd té, of anders niet genoeg. Het is té exotisch, of niet exotisch genoeg. Niet hedendaags genoeg… Het is ook nooit goed: er zijn veel vooroordelen vanuit “the place of power”.’

PD. ‘Dit klopt, maar de place of power is ook aan het veranderen. Dat leren we nu sterk met onze ervaringen in het kader van de Tandemprogramma’s. Precariteit van werkomstandigheden in Noord-Engeland zijn exact dezelfde als in de Balkanregio. De samenwerking is vandaag meer op gelijkte voet. Precies daardoor groeit de interesse in uitwisseling over mogelijke innovatieve werkmodellen.’

CK. Hoe kun je die vooroordelen doorbreken? Wat kan de rol zijn van ONDA?

MI. ‘We mogen niet veralgemenen. Er zijn ook plekken die echt open zijn, en op een heel integere manier connecties opzoeken. Daar kun je echt veel leren. Het gaat over respect, interesse, openheid, nieuwsgierigheid en solidariteit. En de situatie verandert fundamenteel. Kijk naar de ontwikkelingen op wereldschaal. De machtsrelaties veranderen. We gaan naar een situatie met heel veel, gelijkwaardige centra van culturele productie. Gelijkheid en interesse voor uitwisseling tussen die centra is cruciaal en gaat ons uiteindelijk redden.’

Enige reflecties uit het Boedapest Observatorium

Peter Inkei: ‘Budapest Observatory bestaat 18 jaar. We zijn een obervatorium, dus: we kijken. We kijken naar Oost-Europa. Daarmee bedoelen we de voormalige communistische landen. Is dit voldoende als gemeenschappelijke identiteit? Wat hebben we gemeen? Wat is onze gedeelte legacy? Om te beginnen was iets als een ‘onafhankelijke kunstenaar’ voor ons iets nieuws. Daarnaast: de meeste van onze landen zijn natiestaten die toen ze uit het Ottomaanse rijk kwamen in een complex proces van natievorming verzeild geraakten. Op een of andere manier is dat onverwerkte idee van natievorming nog steeds relevant voor onze landen. Nog iets anders: backwardness. Er is het idee dat we minder succesvol zijn dan het Westen, dat we achterna hinken. Niet alleen economisch, maar algemeen. Enkel een selecte elite, die ook wat geïsoleerd was, de urban middle class, keek vooruit. Hun relatie met de lagere klassen is dan weer typisch. Het is het tegendeel van wat Dickens schreef over het Engeland van de negentiende eeuw. Als je Dickens leest, zie je een groot respect voor de working class. Die werden mister of miss genoemd. In onze regio kijkt men neer op de werkende klasse. Tegelijk is er een soort van folkloristisch exotisme. Dit zorgt voor trots, maar is ook een risico. Je loopt de kans dat je gaat conformeren aan een vooropgesteld idee over traditie.’

‘We hebben bij Budapest Observatory een project, de Eurobarometer. Daarin zie je dat Oost-Europese landen andere attitude hebben ten opzichte van kunst en cultuur dan in het Westen. Mensen gaan bijvoorbeeld veel minder dan naar de film dan in het Westen. Als het gaat over wat de EU voor u betekent, dan zijn er in het Oosten slechts weinigen die culturele diversiteit als de lijm achter het Europese project zagen. Hoe we dit moeten verklaren, is niet duidelijk. Maar wel is duidelijk dat je in het Oosten en het Westen van Europa andere attitudes ziet.’

‘Misschien heeft het wel te maken door de verschillende vormen van idealisme die in het Oosten en Westen werden gepropageerd na de Tweede Wereldoorlog. De waarden waren anders, maar in beide zones kun je spreken over hiërarchisch paternalisme. Overal wisten de leiders wat goed was voor de mensen, en de bevolking accepteerde dat. Vandaag is dat wel helemaal veranderd. Er zijn zoveel verschillende leefstijlen, subculturen,… en er is de kracht van sociale media. Daardoor is dit soort van topdown beïnvloeding niet meer van deze tijd. Je ziet wat er dan gebeurt als er een leider opstaat die het volk — in de woorden van Hillary Clinton: de ‘deplorables’ — zomaar gelijk geeft in zijn primaire sentimenten. Zeker in het Oosten is er een grote voedingsbodem voor frustratie, voor jaloezie. Het doet dromen of hopen dat teruggrijpen naar voorbije nationale roem of imaginaire gemeenschappen een antwoord kan zijn voor maatschappelijke uitdagingen.’

Een ander project van Budapest Observatory is de Cultural Policy Barometer: ‘We verzamelden 27 statements over kunst en cultuur, over welke de meest acute issues zijn op dit moment, en vroegen naar wat cultuurexperts belangrijk vinden en waar ze zich aan sturen. Tussen de antwoorden uit Oost en West zijn er opnieuw betekenisvolle verschillen. De collega’s uit het Westen hechten meer belang aan de sociale dimensie van kunst en cultuur. In het Westen werd er meer verwezen naar de sociale betekenis van kunst, als een grote uitdaging. Waarom werd dit in het Oosten minder erkend? Misschien omdat men moet werken in meer precaire omstandigheden dan in het Westen? Een ander issue waar de verschillen groter waren: voor Westerse respondenten was de teruglopende lokale financiering van cultuur echt een hele grote uitdaging. In het Oosten werd dit minder als een probleem aangevoeld. Het grootste probleem van de Oost-Europese respondenten was dan weer: de al te directe interferentie van beleidsmakers in subsidiëring. Op een vlak was er grote overeenstemming: dat er te weinig interesse is voor kunst en cultuur onder beleidsmakers.’

‘Vele mensen zien government spending on the arts als een belangrijke indicator van het bloeien van cultuur in een land. Maar dat klopt niet. In Hongarije gaat er nog steeds veel geld naar cultuur. Het gaat erom hoe die middelen besteed worden. Het aloude dilemma — is de waarde van kunst intrinsiek of instrumenteel? — is misschien verouderd. Kunst is altijd instrumenteel: het sterkt ons allemaal om om te gaan met erfenissen uit het verleden, om om te gaan met een wereld in verandering. We moeten denken over Europa als een metafoor, als een symbool. Niet voor instellingen, maar wel als een symbool voor liberale democratie. Dat moeten we propageren als een waarde, zodanig dat de partners in het cultuurveld zich daaraan kunnen verbinden.’

Vele kunstenaars uit het Oosten zijn verhuisd naar het Westen en werken daar in precaire omstandigheden. Hoe kijk je daarnaar?

PI. ‘Hongarije is een redelijk uitgesproken voorbeeld van een land met een grote druk: de incentives om te vertrekken zijn er groter dan elders. Sowieso zijn de meeste lokale scenes ook heel sterk internationaal geworden. Kijk naar Stravinsky, Chagall… allemaal kunstenaars die naar artistieke centra getrokken zijn. Wat betekent dat? Ben je een exotische vertegenwoordiger van je land? Of kun je vanuit die positie ook iets doen om de situatie in je land te verbeteren?’

PD. ‘Ik moest nadenken over wat Peter zei over de middenklasse. We zijn opnieuw een besogne aan het bespreken van de stedelijke middenklasse. Uiteraard waren we blij, toen wij en vele anderen 15 jaar geleden naar het Oosten trokken en gelijkgestemde zielen ontmoetten. We vonden de Poolse avant-garde interessant en spannend. Maar vele mensen uit de landelijke middenklasse hebben andere interesses en besognes. Wat moeten we daarmee? We moeten hier toch eens even grondig over nadenken.’

PI. ‘Dat is de uitdaging. Mensen in Polen gaan minder naar musea met een minder ontwikkelde traditie van avant-garde in theater en beeldende kunst. Er is een isolatie van de massa. En het klopt dat je met de Erasmus-generatie een meer gedeeld kader krijgen. Maar er is een hele weg af te leggen.’