Beirut Intersections #1. Report on the Lebanese capital’s arts scene

Deze tekst is enkel beschikbaar in het Engels.

To the waterfront. Grasping the resilience in Beirut’s art scene

Privatisation of the coastline is currently a hot issue in Beirut. Many development projects (hotels, resorts, and towers) are being planned as we speak. From ‘the inside’, there almost seems to be no coastline anymore. The feeling you get, as you try, in vain, to catch a glimpse of the sea, is a combination of despair and dismay. As the Beirut Report founder and editor in chief, Habib Battah noted in The Guardian in 2015: “All along Beirut’s coastline it is the same – a development frenzy that has changed the face of the city, wiping out much of the craggy natural shore and replacing it with concreted yacht marinas and upscale resorts.”

While The Beirut Madinati political collective and the Civil Campaign to Protect Dalieh have launched many protests, opposing an existing legal framework that was tailored to benefit landowners, politicians and real estate interests, the plans for a new waterfront business district (Zaitunay Bay) lay bare not so much the false promise of new public access, but the problematic interweaving of large developers (like Solidere) and a certain caste of politicians.(2)

There’s an unspoken vulnerability that assists you as you try to process in a few precious days the recent history of this city’s art movements.

Though we didn’t come to visit Beirut for its waterfront, this state of being cut off indirectly confirmed again what has often been reported about the contemporary city of Beirut: that it ‘is’ a city of disorientation (3), a precarious city also, where a recent history of occupations and violence, sectarian disunity, a garbage and refugee crisis, all combine to the overall perception of a city (and a country) suspended between the weight of uncertainty and the rhetoric of survival in the neo-Darwinian competition of global capitalism (4). Our visit of only five days, for sure, doesn’t justify any thorough analysis or the use of such pretentious container concepts. A city is apart from this, never to be pinpointed, as many different narratives constitute its ‘identity’ at the same time. After a day or two, you ‘know’ that this is also a ‘vibrant’ city, in spite of the trauma’s that still haunt many daily lives. As you attend the IETM conference on the ‘freedom of expression’ in the mornings, and visit Beirut’s many art spaces in the lengthy afternoons, you get the feeling that your personal(ly growing) map of the city shakes with your movements (5). There’s an unspoken vulnerability that assists you as you try to process in a few precious days the recent history of this city’s art movements.

Talking about art, deserves a certain intertextual and historical transition: the artistic strategies of a postwar generation (after the 1990s) have been quite persistent in intervening in representations of the city. What’s more, this city’s artistic productivity has also added to its cosmopolitan attractiveness. Artists like Rabih Mroué, Walid Raad (the Atlas Group), Walid Sadek, Paula Yacoub, Tony Chakar, Ayman Baalbaki and many more have developed internationally acclaimed (mixed-media) practices that circle around the thematic clusters of the loss of identity, mourning, decolonial interventions, phantoms and other representations. History certainly becomes something ‘blurry’ (6) when one has lived through a civil war; it surely explains the somewhat predominant influence of ‘archival aesthetics’, not only in this, but also the younger, upcoming generation (7).

Destruction (also architectural ruins) can be creative indeed (8). That many artistic engagements tap into Beirut’s structural fragility should not divert us too long in this small report concerning my visit of this city that according to some other reports has a thriving and fast-expanding art scene (9). We would rather bring to the fore the ways the rise of new musea, biennales, auction houses, institutions and off spaces have created the conditions for a series of new artistic voicing (10). There is something in the air here: ‘Westerners’ come to Beirut and Dubai because there are new, growing possibilities for its ‘Arabic’ artists. New maps and geographies of connections are being drawn. Too early to tell where this all leads to. Walking the art line in Beirut, it is hard to sidestep the diversity of the most powerful engines like Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Sursock Museum, Arab Image Foundation, Beirut Art Centre, Ashkal Alwan – the latter two situated only several blocks from each other. Actually, we headed each morning for that ‘artsy’ neighbourhood because this year’s satellite meeting of the IETM conference had its base over there (11).

There is something in the air here: ‘Westerners’ come to Beirut and Dubai because there are new, growing possibilities for its ‘Arabic’ artists. New maps and geographies of connections are being drawn.

It was the first time that Flanders Art Institute had asked visual arts curators, working for Flemish institutions, to join its officer of international relations, Lissa Kinnaer, in the participation of a conference that was normally solely meant for artists and cultural workers in the field of the performative arts. In the next five years the Institute would focus more on the (possible) relations with the art scene of the Middle East and Northern Africa. And as the traditional boundaries between visual and performance art became more and more fluid, one considered the possibility of opening up the field in this sense.

There we were, only visiting Ashkal Alwan after that we went to talk to Zeina Arida (Director) and Nora Razian (Head of Programs and Exhibitions) of the ‘resplendent’ Sursock Museum, set in a more residential area of the city. Quite a contrast, as we would reflect on these different settings in hindsight. This museum only reopened in October 2015, and the ‘shock of the new’ is omnipresent. We met with Arida and Razian in the impressive ‘reading room’ of the museum – filled with books of all the usual and less usual suspects of critical thinking, who have become protagonists in the contemporary art world as well. We’ve just visited its running, not so easy to digest temporary group exhibition on matters of ecology. There are also a couple of smaller collections, also of mainly Lebanese artists (painters from the late 1800s to the early 2000s). While being a modern and contemporary art museum, its website states: “Through our collection, archives, exhibitions, and public programs, we aim to produce knowledge on art practices in the region and explore work that reflects on our contemporary moment.” As we sit down and start to introduce ourselves, an impregnating peacefulness fills the whole room. One cannot but be impressed by this new building and its infrastructure. But what strikes us as well, is the elaborate side programme that comes with the exhibition. Razian, who left London’s Tate Modern (as curator of Public Programmes) for this specific assignment in her home country, explains how programmes like these come about. Arida, surely a woman who knows her way around, appears at first a little ‘severe’ but reveals quite a strong and open personality as soon as we start talking about her connections with Brussels. She is clearly occupied with making sure that the museum’s programming has a persistent, continuous future. Though this 19th mansion has been renovated through ‘powerful’ investments by the Sursock Foundation, from what she tells us we can derive it is not an easy job to guarantee this in the long term. Cultural and pragmatic diplomacy in mediating between the Foundation, the state (though there are subventions, she testifies), private sponsorships, the board and her own team, seems to be her daily task. When we leave this mansion, we enter the museum’s adjacent book shop. But my thoughts are elsewhere. I wonder what this museum will be mean in the long term for the young artist. Also, what would it be able to give ‘back’ to the more general public, outside the art world, that seems very tense and dense here in Beirut, where everyone knows each other well.

I wonder what this museum will (…) be able to give ‘back’ to the more general public, outside the art world, that seems very tense and dense here in Beirut, where everyone knows each other well.

Nothing hinted at the presence of something like Ashkal Alwan in that industrial section of East Beirut. This unconventional art school, founded in 1994 by Christine Tohmé (14), resembles the Higher Institute for Fine Arts (HISK) in our own art world in Flanders (Ghent) (15)– although Ashkal Alwan probably has more acclaim when it comes to setting up a paradigm for critique and political discussion that resonates outside Lebanon as well. Its Home Workspace Program (HWP) accepts roughly 15 ‘students’ a year who explore a curriculum and a series of themes developed by its resident professors. The programme supports artists through studio provision, tuition from international and local practitioners, theorists and curators, and the production of locally focused projects. The programme is a real encounter of, in terms of these older epithets, ‘east’ and ‘west’: local Lebanese participants and those from elsewhere in the Middle East form a diverse bunch of artists together with people from Europe, Japan, Canada or even Mexico. A programme like that immediately delivers an insight into the multidisciplinary nature of artistic work today (16).

Wandering through this open airy industrial space where the several studios and offices are literally interconnected and feeding into one another, one imagines this to be a kind of ideal refuge for the visiting artists and others. It s(t)imulates a forgetfulness and critical position towards the art scene of your own origin. As we listen to Mohammed Abdallah’s careful clarifications of the history and mission of this enrapturing place, we can sense the openness and fluidity that Tohmé intended it to have. This space for new relationships does what the ‘real’ political world is incapable of: creating friendships and collaborations in a context where the global meets the local.

Just around the corner, we have an appointment with Marie Muracciole, director of the even more – at least from the outside – ‘uninviting’ (or, ‘invisible’), Beirut Art Center (BAC). Here, an intricate solo exhibition on the ground floor of the Egyptian ‘dreamer’ and ‘musician’ Hassan Khan is a thankful introduction to the function of this center. Muracciole is a convincing signboard for this non-profit exhibition space that employs a small group of young interns – quite an international crowd, where the English language is the lingua franca. Muracciole herself, who is well-versed in the work van Allan Sekula and Yto Barrada, is originally from France (Paris) and is still getting accustomed to the rules of conduct in – at least to her perception – the small art scene of Beirut. When she takes us upstairs to see the small group exhibition concerning two centuries of embroidery art, we come to understand that BAC is planning to continue in pursuing what it is generally perceived to be good at: to pull an international group of contemporary artists to Beirut. Muracciole is clearly fed up with local art practices still being obsessed with the ‘archive’ (she sees its predominance in these epigenous practices of the young student artists). One of her next projects, thus she confides us with some caution, will be a collaboration with the Belgian internationally acclaimed artist Francis Alÿs. The merging noises of the constant presence of traffic jams and construction building, encircle us again on the inspiring rooftop terrace where water clears our throats and minds.

The complex intercultural encounters and political urgencies aside, we come to wonder about the ‘audiences’ of art in Beirut as we have a hard time in really locating its most important private gallery, Sfeir-Semler. We become trapped in the impossible or inexistent pathways at the waterfront again. When we do reach our destination, we step into an elevator that shoots us to the upper floor of a building that from the outside could be a warehouse for any goods except art. As soon as one steps into the gallery itself, one cannot help thinking about the neoliberal homogenising force in the art world. We are in Beirut, but this place could be anywhere. It is larger than, and neater, than life itself. This must be a private space. The windows are whitened. The outside world is, well, just outside. The feel of the whitewashing (of the real diversity in each nation) clashes with the artistic practice that it currently houses. The ‘local’ Lebanese artist Haig Aivazian surprises in ‘the black box’ where his video installation ‘Hastayim Yasiyorum (I am Sick but I am Alive)’, through the historical intertwinement of the region’s musical traditions, “reflects on the sheer violence exerted by borders on the one hand, and their perpetual incapacity to curb waves of sound and human migrancy”. Specific information, faces, and architectural settings crowd this video while migratory (Armenian) musical patterns constitute the appealing leitmotif, bringing together the many (voices) and the one (an Turkish-Armenian Oud master, Kenkulian).

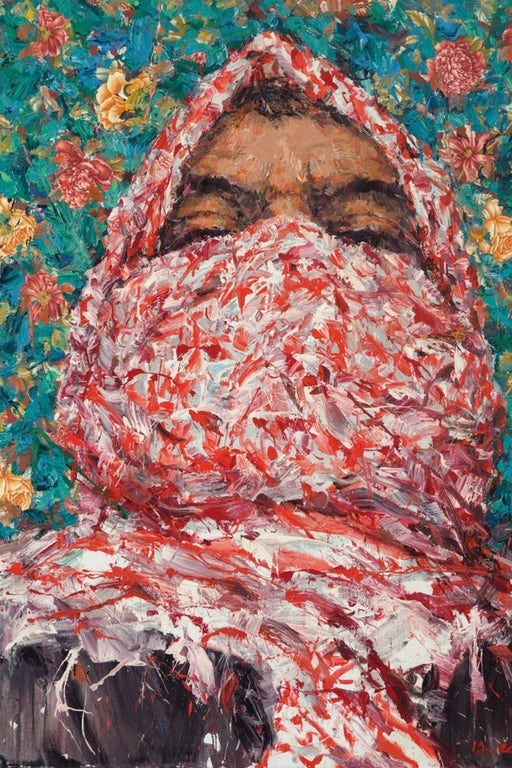

These rooftops, facing the sky, become ‘faces’ in themselves. I peer into their eyes as if looking into one of Leibniz’ monads and hoping to see a whole world come to life in one painting: Beirut’s art scene.

Back at home, I ponder over rooftops. I don’t know why. In the film ‘Je veux voir’ (2008), main character Rabih Mroué tells Catherine Deneuve that he thinks the high-rise Murr tower should stay, as a reminder of Israel’s war on Lebanon in 2006. In his own play ‘How Nancy Wished that Everything Was Just an April Fool’s Joke’ (2008) the top of this tower becomes the setting for a meeting between four old fighters. The artistic reappropriation and reimagination of post-civil war Beirut is also what happens in the paintings of the Senegalese artist Claude Moufarege who is currently, so I notice through my new friendship on Facebook with Art Space Hamra, exhibiting in Hamra street. We must have crossed the street, but we haven’t visited this gallery. Now, I look at Moufarege’s rooftops with a combination of lingering nostalgia and powerful reverb. These rooftops, facing the sky, become ‘faces’ in themselves. I peer into their eyes as if looking into one of Leibniz’ monads and hoping to see a whole world come to life in one painting: Beirut’s art scene.

Beirut and Cairo have both become important independent art hubs in the world, now that the biennales in the Middle East have become more important. Both ‘art cities’ try very hard not to simply ‘mirror’ the (Western?) developments elsewhere. Our brief exploration of what is happening on this side of the waterfront, lays bare this ‘fact’ (17): In between the logics of the private galleries and the ‘semi-semi’ musea, there exist many hybrid spaces that see it as their mission to take care of the local (educational) structure while addressing the whole art world. If anything constitutes a promise of a resurrection, it is this resilience of the ‘local’ art world and its different players (and funders). As Judith Naeff stated powerfully: “The resurrection of tradition – and with it identity – through art promises a renaissance, the reconstitution of Beirut as a city with a conventional cultural tradition that gives meaning to its present identity.” (18)

Notes & sources

- I want to thank Flanders Art Institute for the opportunity of exploring of Beirut’s (visual) art scene, together with Lissa Kinnaer and Mieke Mels.

- Ironically, the painting “Le Port de Beyrouth” (1954) by Mahmoud Saïd is one of the most expensive works by any Egyptian artist.

- ‘A letter from Beirut: Disoriented Libanon’

- To better understand Beirut’s ‘suspended now’, I refer to J.A. Naeff’s recent PhD thesis with the same title: Beirut’s suspended now: Imaginaries of a precarious city, 2016 (Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis).

- I make reference to Mona Hatoum’s “Map (clear)” (1999), which is an arrangement of clear glass marbles in the shape of a world map on the floor that moves and shakes with the viewer’s movements, and creates a hostile surface to walk on.

- On the impossibility of a linear timeline of Beirut, see the work of Lamia Joreige. Her ‘Autopsy of a city’ (2010) questions the validity of a comprehensive, complete history.

- It’s telling in that regard, that Randa Mirza’s photographic series, ‘Beirutopia’ (2011), was projected in 2014 on the blank walls of Berlin’s Archive Kabinett.

- Naeff ‘reads’ Rayyane Tabet’s Peeping Tom’s Digest (2012) in that way in her article on ‘Disposable architecture – reinterpreting ruins in the age of globalization. The case of Beirut’, chapter 14 of the already mentioned PhD thesis.

- artsy.net

- See also Nat Muller’s ‘Who’s afraid of representation? Vijftien jaar kunst uit en over het Midden-Oosten in het Westen’ in Metropolis M, okt-nov nr. 5, 2016.

- What’s more: According to Fatenn Mostafa Kanafani in Rawi (Egypt’s Heritage Review), issue 68, a landmark new museum is planned for Beirut as the Lebanese-Palestinian art collector Ramzi Dalloul has ambitious plans to expand the global reach of modern and contemporary Arab art.

- Let’s Talk About the Weather: Art and Ecology in a Time of Crisis, curated by Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez and Nora Razian.

- Interesting to contrast this with the other more underground mansion that we visited the next days. Originally an, as so many ‘ruins’ in Beirut, abandoned place, this ‘multi-purpose collective space’ is a hub for experimenting in living and working together in the arts in Beirut. All the important players have a connection to this place with a lot of ‘street credibility’.

- Who has recently been appointed curator of the 2017 Sharjah Biennial

- Interestingly, Rachel Dedman (see the next footnote also) makes an important distinction here: “(…) and yet they arise in response to quite different problems. Not intended to highlight and resist the pernicious reduction of education to demands of a market, or use the Internet for global connection, these non-western initiatives counter an absence or insufficiency in their society, and use the internet to broaden their artists’ horizons. They are characterized, therefore, alongside the excellent work they do, by an embeddedness in their local context.”

- Rachel Dedman’s ‘Knowledge Bound. Reflections on Ashkal Alwan’s Home Workspace Program, 2013-2014’, which recounts the formation of this kind of network and what it can lead to, within the modalities of the programme, is quite an exceptional, ‘productive’ trip

- Though that doesn’t imply that Beirut’s art scene is a very collaborative art scene. Not sure what ‘working together’ could mean in this context. All the mentioned players see a different role for themselves, but this self-perception seems quite unrelated to the role of the other in the whole scene. Just an association that needs more research.

- ‘Absence in the mirror: Beirut’s Urban Identity in the Aftermath of Civil War’, Contemporary French and Francophone Studies, 2014, p. 556.