Taking Time, Making Place

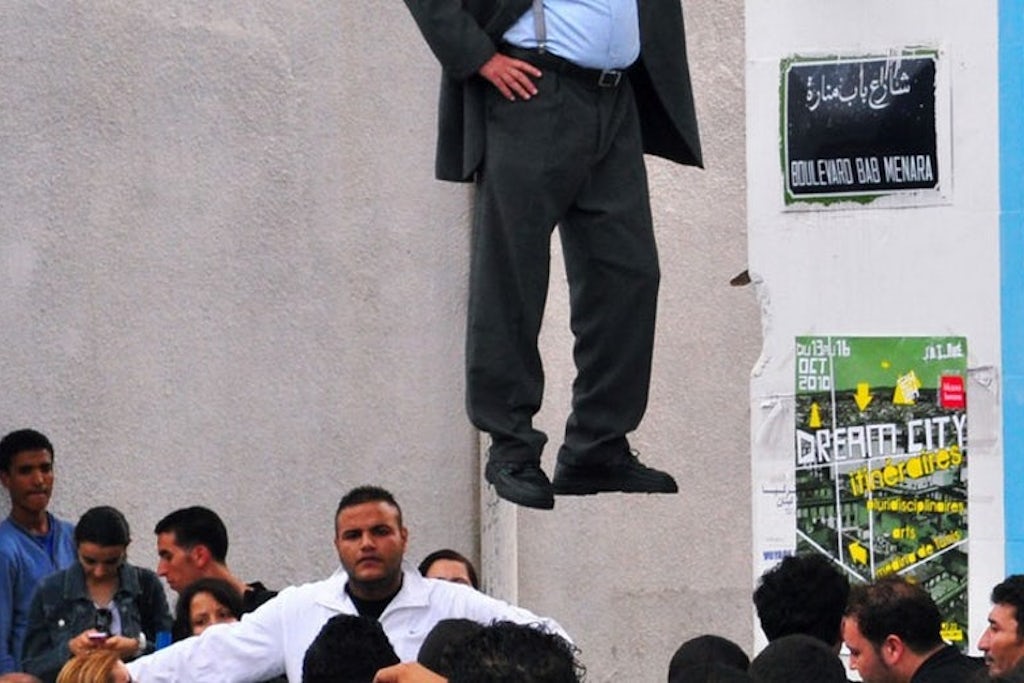

Johan Lorbeer, Tarzan/Standing Leg, Dream City 2010

As a brother and sister team, Tunisian choreographers and dancers Selma and Sofiane Ouissi (b. Tunis, 1975 and 1972, resp.) form a unique artist duo, integrally binding artistic and social engagement in every project. Their art investigates the conditions of living together. They want to ‘dream’ different communities, employing the wealth of the human body in order to see what powers are alive in our social relationships to create another sense of community. Ten years after they breathed a public life into their dream in the Medina in Tunis, in the form of Dream City, now a multidisciplinary, biennial festival for contemporary art, I spoke with them while passing by in Ghent, on a warm, late summer evening. They were openhearted, without reservations. Their voices melded together, assessing, testing, within the context of a shared vision, looking back and looking forward. ‘The question is: do you want to do something for the world you live in or not?’

Selma and Sofiane grew up in Tunis and trained as dancers there. Since they began creating works that were internationally widely performed, such as STOP….BOOM (2004) and Waçl (2007), they have been viewed from far and wide as figureheads of the contemporary Arabic dance scene. A choreography such as Here(s) (2011), which they created in real time via Skype, together with media artist Yacine Sebti, is no exception to that status. Nor is the success that they have enjoyed following a commission from the Tate Modern to create a work for a worldwide Internet audience, entitled Les Yeux d’Argos (2014). The traditional image of Arabic art, inevitably and endlessly reproduced for tourism, as a craft or inherited tradition, here makes way for a contemporary practice, one that seeks loopholes in everyday social environments in order to create previously unseen public connections. With Selma in Paris and Sofiane (back) in Tunis, that may as well be simple necessity. Although with them, the friction between creating art and living together stems from an integral artistic démarche.

In the intense collaboration that defined them from the start, they no longer approached ‘dance’ as an objective in its own right, in the classical sense, but as a method for engaging in dialogue with a context, and in this way to make public that which is invisible, inaudible or marginalized to that particular context. Taking the time, making a place for the other, making direct contact, and focussing attention on the human body are, for them, not just idle words, but real gestures in a post-disciplinary practice that always and everywhere relies on local encounters. It can therefore be perceived as both poetic and political. Laaroussa (2013) is characteristic in this connection. It is a choreographic performance based on age-old, ritual gestures of women potters in the Tunisian village of Sejnane, as well as the result of a group process that lasted several years, in which dance served to give back a worthy self-image to these women, as well as setting up the beginnings of self-organization for their community.

All of our projects take their meaning, their sense, even their direction from an immediate relationship with the local social context.

Their recent Le moindre geste (2017) is comparable, because of the importance of that group process. It evolved from a European collaboration between the Museum of Fine Arts (MSK) in Ghent, Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona and the FRAC Lorraine in Metz, with performances at Festival Passages in Metz and the Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Brussels, which has been following Selma and Sofiane for some time now. For this project, they engaged with very diverse local communities in Metz, Brussels and Ghent, in search of the revolutionary power of the small gesture to transcend social and linguistic barriers. Based on this, they created an installation with performance, illustration and video, which allowed a broad public to come eye-to-eye with the life stories of fellow citizens living in the margins. The content of each performance is different, because the deciding factor is always the specific local context. Selma and Sofiane moreover seek out precisely that feeling of empathy with what does not fit into the official narrative.

Concrete proximity is crucial here, with the body as a membrane between private and public. When I spoke with the Ouissis, they had just returned from an intense visit to the prison at Oudenaarde. By way of coaching from the Museum of Fine Arts, prisoners had worked with the protocol that they had made for Le moindre geste. But they also felt they needed to meet the Ouissis in person, to know just who they were. It was a highly emotional moment. ‘We do not work with a protocol like that in order to conceal ourselves as artists, but to become unseen, invisible,’ they explain. ‘It is a way of giving the space to the others, so they take it into their own hands. This way, we avoid any artistic discourse imposing itself on what is taking place. We can’t stand that. As artists, we impose no gestures that put us in the middle of the creation. In this case, those who were involved really wanted to speak to us in person, so that made the meeting very delicate.’

Their presence speaks volumes about their engagement – humanist, going into the breach for their contemporaries. For Selma and Sofiane Ouissi, however, all this is utterly self-evident. ‘All of our projects take their meaning, their sense, even their direction from an immediate relationship with the local social context.’ Nonetheless, the time that they take, or make, is remarkable, especially since at the very time of our meeting the next edition of Dream City in early October 2017 is in full and intense preparation. Dream City is an initiative of L’Art Rue, a collective that the Ouissis established in 2007 for the production and dissemination of contemporary arts in Tunisian public space. As a biennial festival it has been ensuring and honing interaction between the arts, the public and the city of Tunis since then. In a time of dictatorship (three years before the Arab Spring in 2010), the first edition gave expression to a desire to reinvent art on the spot, to ask ‘what people were looking at and who was allowed to look’, what freedom was permissible and what role the artist had regarding it. Ten years later, that desire still burns. Have the artistic questions of the Ouissis changed in the meantime?

S&S: Do artists and the arts they practice truly make up part of a societal project? This is the larger question that concerns us. We find it our duty to keep asking it, because we think that art should effectively serve as a part of the construction of a society, as a dreamed, or dreamed-of construct. What do you do for the place where you are? L’Art Rue collective is our answer to that question, not only in the form of Dream City, but also in its attention to art education, support for contemporary Tunisian creation, a magazine, the Laaroussa art factory in the Tunisian countryside, and so on. We clearly devote a lot of time to it, but it is our way of helping to build the structure of our country, as a dreamed society. We are not just doing it for ourselves. We also try to find working methods to support other artists in finding local anchorage for their projects, so that our work, as it were, is constantly doubled, and unfolds in a democratic space that is open to everyone. In that way we want to create dreamed-of spaces. And in doing so, the support and the assistance we give to others, the giving itself is essential.

Our work establishes a protocol, a framework, a project, a concept that can be shared by people who would otherwise not meet one another.

What do you exactly mean with the recurring theme of a ‘dreamed’, or ‘dreamed-of’ space or society (espace rêvé; société rêvée)?

S&S: We are talking about ‘dreamed’ in a utopian sense, but in a very concrete way. Take the prison that we have just come from. That is a dreamed society, because we meet people there whom you normally may not and cannot meet, people whom other people are constantly judging and with whom you spend no time, because the regular society has decided the way it has. Our work establishes a protocol, a framework, a project, a concept that can be shared by people who would otherwise not meet one another. As a result, the rules of the society are shifted a bit, and something becomes possible that would otherwise be unthinkable. That also explains our need to be physically present somewhere, and to work completely from an actual physical proximity.

Does the need for physical embedding in concrete situations explain why you are almost completely absent in the virtual sense? There is a real dearth of information about your work on the Internet.

S&S: It is true that promotional dissemination of our work does not concern us. We do not have a website of our own. That has nothing to do with any rejection of modern communications media. On the contrary, Skype is one of our artistic tools. But we prefer to remain in the margins, and to work from immediate physical contact. We have no interest in the economic system of an art market that revolves around marketing and consumerism. We first have to get to know people and the art centres they work in, in order to see whether we can really work with them. The distribution of our work is through stories told mouth-to-mouth, and even then it can happen that a theatre or a person who invites us does not appeal to us, for example, because they deal with time differently. We are not a product. We seek a dialogue that can carry on through time. That continuity is something we need. And that never happens straightaway. It is not easy to just instantly expose or reveal our practice on demand.

So time is the very matter that your work and your working method primarily require?

S&S: Absolutely. Moreover, as an artist, you have to be able to give yourself time as well. But that is not obvious in the contemporary art world. The institutions play a major role in this. They kill off the way of experiencing time that we stand for. Most museums are factories. They place orders and constantly want something new, something that has not yet been presented. But this creates a bulimia in the circuits of programmers and curators. Curators who invite you to take your time are rare. They want efficiency, because, of course, they have to account for themselves in the context of the numbers of tickets sold. The result is chronic, permanent stress. But is that really the way art is created? Is the size of an audience an indication of the quality of a project or process? We absolutely do not want to be efficient. The focus on results merely ensures that curators or artists no longer ask themselves why they are doing something or how they achieve something, when in fact, that is the only thing that matters if you want to appeal to an audience.

How do you mean?

S&S: What matters is not the result, but how you get there, the urgency with which you proceed. Showing that how and why offers people the space to become poetically and politically engaged. The question is therefore how you can create a process in which the generosity is already built in. For it is precisely in connection with this generosity that we find ourselves in crisis today.

Is your way of dealing with time an answer to that very crisis?

S&S: Yes. For Dream City, for example, we are inviting European artists to spend time immersing themselves in the city before they begin. All we are asking is that they take the time. It often confuses them, but in a good way. Jozef Wouters, for example, who is taking part in the 2017 edition, has completely changed his approach as a result. So taking the time is simply essential. You cannot expect an artist to just constantly produce all the time. It is unhealthy and even a violation. It means you create vicious circles. Sometimes a project takes several years. That is not something crazy – it is just normal.

Ten years have passed since the first edition of Dream City in 2007. Has the time that has passed since then also had its effect?

S&S: Yes, a lot has changed since then and now, but not in terms of our method. From the very beginning, we felt an urgency to involve unconventional, public places in Tunis and to work there in a collective way with other Tunisian artists. But it was certainly never our idea to begin a biennial project. It was originally about a one-time creation, a project in consultation with Frie Leysen of the Kunstenfestivaldesarts. It was at the request of the public that the initial artistic project grew into a biennial event.

An instance of being in the right place at the right time, shortly before the Arab Spring?

S&S: It was a real turning point, for the audiences as well as for us and other artists. It was an artistic coup d’état. It all began live, on radio, when we made a call for a peaceful march by all artists and art students, because we wanted to show the government how many of us there were, without anyone having a decent artistic statute. Yet, that was actually a bit naïve of us. In a dictatorship, you are not allowed to speak out certain things, actually say such things as ‘President of the Republic’, ‘government’, ‘march’, or ‘occupying public space’ out loud, and we had in fact spoken them all of them out loud. The result was that the broadcast was immediately intercepted, and the journalist who had invited us was removed for a long time. Everybody around us was really terrified, but we did not ourselves live in Tunis at that time, and that saved us.

But the story did not end there…

S&S: No, it didn’t. Direct confrontation with censorship made it just physically tangible how public space in fact did not belong to us. It was at best an instrument for the propaganda of the head of state and his government. You were also not allowed to come together in public space with more than three people at a time. In our creative work, however, we already had the habit of installing a laboratory for reflection, in which we could open up our artistic methods and materials to students who could make use of them for their own creations. So when we tried to think up a concept whereby people could peacefully and innocently walk through the city for art, we continued along that path. We began to carry on discussions in order to assess who was interested, and based on that, we wrote down the whole methodology and the concept.

What are they?

S&S: Methodologically speaking, we had the idea of surrounding ourselves with artists, philosophers, sociologists, art critics and journalists, and to support them in realizing their creations in situ, in unconventional and public places. We asked them to show how they dreamed of their city, in their own (artistic) medium. The title Dream City originally came from that theme. Moreover, as an extension of that dream, we decided to completely ignore all financial concerns. Every time we returned to Tunisia, our experience was that artists indeed had no place and no resources, but because of that, they were constantly complaining about everything. We wanted to turn that negative energy around, so we asked ourselves what we could think of together: how can we, together and without financial means, try to conceive of a work that establishes and maintains contacts with others? How can we forge a collective energy that is stronger than what you can do on your own, that makes things possible that you could not achieve on your own?

So the idea of a work of your own changed into a decision to work with and for others?

S&S: It seemed senseless to us to try to set up a work alone. That would never have had the same impact. We could not march for our own art ourselves, of course, the public had to do that. Moreover, that choice was also an answer to another crisis that we were experiencing.

What crisis was that?

S&S: At the time, we had already been working internationally for a while, but after our performances, we had come to notice that we were generally always performing for the same kind of audiences. We could easily grow old bowing to the same applause, we thought, as if we were performers for a royal court. But that is not art. That was simply not what we wanted! For us, that too seemed like a form of dictatorship. You are mostly busy protecting the amount of money you’re collecting. And sooner or later, you become politically recycled. We asked ourselves: is that what our work is for? Is that what we want to do every evening of our lives? Dancing for the bourgeoisie of Tunis? Doing that, we would never really succeed in creating freedom. We kept asking ourselves where the young people were, or the people who were not being admitted.

And that led to the idea of moving into the city and coming together at changing places?

S&S: Exactly. Although we also needed a tactical plan in order to do that. During the dictatorship, we did not have the right to do what we wanted. We had to move underground. We regularly met with about 20 artists in Sofiane’s small living room to discuss who wanted to realize what and where. We also needed to select an appropriate date, which eventually was the anniversary of the Ben Ali coup d’état in 1987, on 6 and 7 November.

Why was that an appropriate time?

S&S: Because all government agents would be at the presidential palace for the national festivities! Nobody knew anything about it. We were only able to give substance to our plan the day before, because we were not permitted to communicate. On the morning of the opening, Sofiane was even taken to a police station with 50 agents, whose boss was constantly yelling, ‘What do you mean, all those artists in public space?! Just where do you think you are going to go?’ That was heavy. But suddenly it turned out that there were masses of young people all out in public spaces, in the thousands. And 7,000 to 10,000 people in the streets – that even intimidated the police! Nobody had expected that, not even us. That is what is so incredible. You think, and you work, but you actually don’t know that there are so many people interested in this aesthetic, artistic project. But they are. Those huge numbers of people were our salvation. The lesson was that the people were already there.

And they asked you to come back?

S&S: Yes. It was on public demand that Dream City went from being a one-shot thing to a biennial. There were also many artists who were pushing to continue. We took them out of their theatres and galleries to place them eyeball to eyeball with the community. And that in turn opened them up as well. That caused their practices to shift in ways that they also found very interesting. But the mass interest also had a downside. During the second edition, which was again open to local artists, it seemed as if we were having to carry the entire artistic community. That was too heavy a burden; it became a ghetto. So we were thinking that we couldn’t do it anymore. This was not our mission. From that point forward, we invited Jan Goossens to come help us out.

What did his arrival bring with it?

S&S: In the first place, Jan saw to it that there was a buffer between us and the other Tunisian artists. It was too big a burden for us to have to choose between artists to whom we were so close! And at the same time, you have to be able to objectively say that somebody must be left out. Jan also insured the necessary opening to the international circuit. That is one of the most important differences from the first editions, and it still keeps on stimulating us today.

If you remain together as members of the same culture, you cannot keep learning. At the same time, that opening up to the international art world has also helped us realize that we needed to anchor our work much more solidly.

In what sense did that international dimension alter the process?

S&S: Someone from the outside who looks in at your society causes you to take ten steps forward, compared to someone who is completely in the middle of it and has no overview of the whole. The confrontation between those two perspectives is interesting. You learn a lot about people and about the world. If you remain together as members of the same culture, you cannot keep learning. At the same time, that opening up to the international art world has also helped us realize that we needed to anchor our work much more solidly. And that we had to incorporate more time. That can take place through working with other groups of people or it can entail exploring and trying to understand the places where those people live more closely.

Is your project with the women of Sejnane for Laaroussa an example of that?

S&S: Yes, in a certain sense it is, but Laaroussa came about entirely separately from Dream City. In October of 2010, just before the revolution, we were in a beautiful country region. We were extremely interested in the way the women behaved and the ancestral, gestural character of their gorgeous pottery culture. They lived isolated from each other in unsightly hamlets, not in a community, so we decided to go from door to door in order to tell them that we would like to do a project, as well as assess what the women themselves would like. We had nothing more to offer than our art, so what was it that they themselves needed in order to get started? What they answered every time was ‘time’ itself. Those women needed time for their work, because it was not acknowledged or recognized anywhere, by anyone, as anything even vaguely artistic, and they moreover combined it with caring for their children and maintaining their households in poverty-ridden conditions.

So next to their craft, they all actually shared a basic need for time?

S&S: Exactly. So with that in mind, we returned to Tunis to write out a project that would ultimately last for three years. In the first year, we invited lots of diverse artists who could, together with those 60 women and their children, create a kind of dream horizontal society. Each of us chose a role that he or she wanted to do every day for that community. We based it on the local reality. The children had to be cared for, so there were artists who decided to open up a kindergarten and work there. The region has very little water, and people always had to fetch it from far away, so some did that, while others cooked. The landscape is vast, and the mobility of the women is limited, so we also organized minibuses to pick them up every morning and take them to a place where they could get to know each other and learn to work together. That had never happened before. The horizontal structure helped clarify what could be achieved with the division of labour and by working together.

Was that the ultimate goal of the whole organization that you set up?

S&S: Our first idea was that ultimately, at the end of the first year, everyone would offer something to that community. We chose to make a choreographed video of their gestures and to archive it all in that way: not by interpreting those gestures, but by reflecting them, and giving them back to them. The gestures that you make every day are gestures that you no longer see, but if someone sublimates them and mirrors them back to you, you notice them again, and they can suddenly have a great affect on you. The women wept when they saw the video. It was also a gift especially for them – not something to be distributed elsewhere. The fact of giving itself was central to the project. The factory that we established as a result lived on for three years. After the project had finished, UNESCO recognized their expertise as immaterial patrimony, which was huge news for everyone. The only thing that we think is a shame is that we were unable to continue on with the factory. We searched, we tried. The structure was there, but we could not find the right people or means. But in the meantime, the women themselves had learned to work together, and they are still doing that. That remains.

We don’t have references. We are not ‘inspired’, so to speak. Or to put it differently, our inspiration comes from where we go. It is visceral. Our work starts out form the encounters, and within them, we experiment and fabricate, but we have no words to place above them.

In artistic circles, did people think it odd that the makers of an urban contemporary art festival would work so intensely with a rural craft culture?

S&S: No. Right after the revolution, there were dozens of artists interested in regions like that. Moreover, Dream City generated other projects in those rural regions. For example, we had an edition that took place at the same time in both Tunis and Sfax. But that was too complicated. We wouldn’t do that again. You cannot go out in search of being anchored locally at the same time in both Tunis and somewhere else. But that is also not necessary. For the 2017 edition, we have invited artists from different regions to get to know our construct and our method, and then they can do whatever they want to do with it. We cannot do everything ourselves.

Did the question of ‘how to share an artistic practice’ that arises in Le moindre geste evolve from that? With the idea of a shareable, freely applicable protocol as an answer?

S&S: Partly. FRAC Lorraine had asked us to redo Laaroussa in Metz, but that seemed impossible to us because of the local anchoring, so we developed Le moindre geste instead. ‘What is the connection to the city in this particular case? What is the need that Metz itself has?’, we asked. In Laaroussa, it was clear that the women involved all shared an expertise, but what is shared in Europe? That was already rather more complicated.

How did you go about then?

S&S: We never work from a preconceived idea. The idea always evolves from a meeting with others and through the friction that we seek with the area in which we work, so we began to speak with local organizations and associations in order to gain some fuel. On the one hand, they pointed out people in the city who were marginalized, all those people nobody hears. On the other hand, they spoke about the presence of foreigners, people who are categorized according to stereotypical questionnaires into bureaucratic indexes, and idiotically enough, about whom the most important thing seems to be that they learn to speak the language, become integrated and culturally recognizable.

So what idea did you develop out of these local conversations?

S&S: Our idea was in any case not to get in between the many population groups that we met and point fingers or stigmatize them. We wanted to create an open space. We asked ourselves how we could help repair the conversation between people and groups. How can we create a space in order to speak? How do you take the time to really look at and listen to one another? What can bring together and re-establish bonds amongst people who have nothing to do with each other, in a way that means that they are all engaged with the project? We felt that we had to start out from something that all people share in common. So we came to a protocol of five interview questions around the life stories of the participants. Who is the other? What do I share with him or her? Well, the answer is precisely that individual life story. Our protocol functioned as a kind of musical score for sharing widely diverse life stories. And consequently, the participants themselves were able to determine the directions that they took.

Do these performances still bear your signature?

S&S: We don’t want any signature! We always start out from the unknown, without an idea, in search of a concrete necessity, the need that we feel in a concrete place. It is because of the degree to which we dig deeper in a place that the idea slowly presents itself. What interests us is that investigation, always putting ourselves at risk, again and again. We throw ourselves into the middle of a situation that we are not familiar with and know absolutely nothing about.

Are there any fixed anchor points, or recurring references, that inspire you in doing so?

S&S: No, we don’t have references either. We are not ‘inspired’, so to speak. Or to put it differently, our inspiration comes from where we go. It is visceral. Our work starts out from the encounters, and within them, we experiment and fabricate, but we have no words to place above them. In the meantime, we know how it works for us, but there have also been other times. We have often been confronted with programmers, primarily French, who constantly wanted to put us in a specific framework. They felt that as artists, you had to have references. But it bothered us to have to pretend that we knew something, that we had already found our way, as it were. For we may be standing here today, but tomorrow we are somewhere else. Perhaps that works because there are two of us. That is a strength. In that sense, our own life trajectories are our only reference.

I see, but doesn’t every life have particular influences?

S&S: Certainly. Perhaps our family is one of those influences – a family of opponents. Among our grandparents’ family, where we spent a lot of time, there was an aunt who was an artist, and was involved in Sufism. She was always bringing in other people. She opened the door to everyone: all the artists in the neighbourhood regularly came together, and even the gentleman who held open the door to the building was welcome. Those moments of exchange, that intellectual breeding place, with all those people who went to theatres and to concerts, to the cinema – all that certainly influenced us. It is ultimately perhaps even true that it is this atmosphere that we are always trying to rediscover. But in the world of dance, for example, in which we were trained, if you speak about influences, then what they are talking about are influences from a specifically aesthetic handwriting. And we have always rejected that idea of an aesthetic signature.

Why?

S&S: Again, that has to do with the anchoring. We feel the need to ensure that every gesture is grounded: that it is justified, or justifiable, and useful to society. We need to have a relationship with real life. In that sense, we have an aversion to all aesthetic discourse. There are artists who can do that, but for us, wanting to be at the centre of one’s own discourse feels like a hindrance. We do not believe that you can impose a discourse like that on the world, unless it is grounded in a deeply lived experience of things. It is because things touch you or move you that you feel the need to find words for them, not the other way around. In dance, it works the same way. With every creation, we always start out from the body, seeking to find the necessary attitude towards the issues that the body confronts. Going into the studio consequently means asking ourselves on which body and with which approach we are going to work. It is precisely this that requires so much time for thought. Because, if you do not record or fix the handwriting, you do not know whether what you’re doing is right. You work and you think more by feeling, by testing it out. Little by little, however, we actually stopped dancing altogether.

Because that was never the objective in itself, having no focus on an aesthetic signature?

S&S: Indeed. Moreover, we also wanted to make a radical break with tradition. People need traditions because they are frames of references for how to do things. But what if that means that all you’re doing is repeating the same references? At one point, we said to each other that we were going to stop going to the studio and maintaining our bodies the way we had always learned to do. We wanted to be able to get closer to the everyday, ordinary body, instead of striving for sublime perfection. That was a very clear break, a break with a certain idealism.

Did you really finish with ‘the dance’? Or did you begin approaching dance differently?

S&S: Well of course, we certainly have a great deal to thank dance for. It awakens a mystical, spiritual dimension in you, while at the same time allowing you to feel and touch one’s body from very close by. It brings you in contact with the respiration of life itself. But dancing is more than a technique. For us, what dancing is about now is a total charging of energy that displaces itself within a certain experience of time, in relation to the other, with a sensibility of the senses for looking, touching… As soon as we saw that, life itself suddenly became a dance. The most unguarded gesture of life is for us a true gesture, with a real time and a real musical handwriting to it. Reading a body is therefore also such a passionate thing – it tells much more than what words can say. It is the aesthetics of dance that we are pushing as far away as possible, to the point where a transformation takes place, a radical physical and visual experience of transcendence, silent and intense. From there, we then ask ourselves what that means for the posture of someone who receives that experience, who gets insight into the process that has taken place.

What do you eventually consider to be the source of the desire for human encounters that so animates your work?

S&S: That’s hard to say. There is a very instinctive, animal side to physically feeling the other. To immerse yourself into another, to be in someone else, engenders a transformation of yourself. So we are very seduced by the other. And this also has something to do with love, a deep faith in people and in mankind. Time and time again, we want to discover a new way of existing for and with others, others who are different. Precisely because of that difference, these others touch us, confuse us, make us breakable. You realize yourself through the other. So it is that concrete look of the other that we are searching for, not the look of the audience in a darkened hall. In order to feel that we are alive, we really need that singular, individual look. It can sometimes be utterly invasive and intense, but it makes us question ourselves.

Are you two also that singular look for each other?

S&S: We have been very close to each other since we were children, more than with other family members. Perhaps that explains why we are always looking for an encounter with that look. We constructed ourselves that way. So yes, it is not without significance. We have made and shaped ourselves by way of the look from the one to the other.