Subjectivity and locality in a transnational sphere

We live in an age of superdiversity under the influence of migration and global transactions on an economic and cultural level.

Cultural diversity is complex because, in these days of digital media and mobility, migrants remain in close contact with their homeland. ‘Here’ and ‘there’ are closely interrelated and identity is something plural. Those relations are loaded with colonial histories and feelings of superiority. For the places that welcome migrants too, this represents a challenge: who are ‘we’, and what is the relation with the nation state we belong to? Instead of talking about globalisation, it is more appropriate to talk about negotiations between different places, each with their own complexities and histories, which in turn relate to complex forms of subjectivity. That negotiation takes place pre-eminently in culture. Artists and art mediators like programmers or curators also migrate and introduce a piece of their culture into that other culture, while at the same time staying in contact with their homeland, where they sometimes play an active role in the arts sector. They act as citizens who, not restricted only to their passport and nationality, are affected transnationally by certain political issues. They bridge the different economic, social and political contexts in which art is made in different parts of the world and bring local complexities into dialogue with one another.

Hicham Khalidi – born in Morocco, raised in the Netherlands, living in Brussels, working in Paris and Rabat as well as in other places in the world – reflects on his role as a curator in this complex environment. Dirk De Wit (Kunstenpunt/Flanders Arts Institute) proceeds from that transnational reality to raise questions about the role of intermediaries and about the international cultural policy.

Where are we now? To whom do we ascribe ‘Moroccanness’?

By Hicham Khalidi

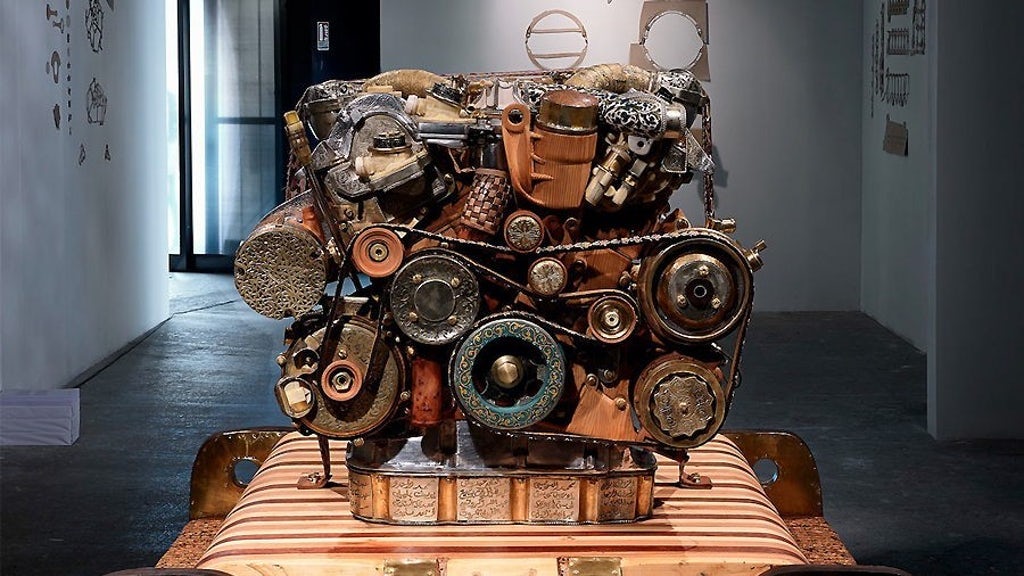

Let me begin with an anecdote. As curator of the 5th edition of the Marrakech Biennale in 2014, I commissioned a performance by Jelili Atiku entitled I Will Not Stroll with Thami El Glaoui. For this work, the artist rode to Jamaa El Fna in a horse-drawn carriage followed by a flock of fifty sheep. Hundreds of people gathered to watch the procession. In the distance, I saw people flouting the rules and standing on the roof of the Biennale’s main exhibition venue, the historic Bank el Maghreb. Because we’d decided not to charge an entrance fee, the building was teeming with locals. One of the highlights of the exhibition was V12 Laraki by Eric van Hove: a complete replica of a Mercedes V12 engine that had been made by local craftsmen. In awe of what Moroccan artists and craftsmen could achieve, some of the visitors even started touching the works or adjusting them on the walls. With great pride, they would say: “This one is ours”. Families with children visited the Bank el Maghreb and mothers would make their babies kiss the beautifully crafted works that had emerged from Van Hove’s studio. Given that the Marrakech Biennale was on a mission to make the event more accessible to local people, this was truly a moment of which Vanessa Branson, its founder, could be proud. All of this took place to the great astonishment of the hundred or so international journalists who had gathered for the opening speeches. Meanwhile, I was on the telephone to the management of the Biennale begging for cash. Once Jelili’s performance ended, I knew that the shepherds would request immediate payment. And to my utmost bewilderment, there was no money.

“Can you please add more Moroccan artists to the list? Twelve or so would do.”

HICHAM KHALIDI

These were the circumstances in which we worked for two years. We were exploring new subjects that we never previously addressed whilst also grappling with a host of practical challenges and learning curves. Two years earlier, when I’d won the pitch to curate the Biennale, Vanessa Branson had asked me: “Can you please add more Moroccan artists to the list? Twelve or so would do.” I was surprised by the question. What did she mean by ‘Moroccan’ artists? Were they living and working in the country, or the diaspora, or did she have other ideas? Would the Belgian artist Eric van Hove, who has been living and working in Morocco for the past five years, qualify as a Moroccan artist? Did she mean contemporary artists? Because, after all, this is the trade in which we are dealing. We deal in subjectivities, I thought, and everyone’s opinion matters. But how could this help us define contemporary Moroccan art?

Looking at myself, a Dutch-Moroccan, and my assistant-curator Natasha Hoare, English and born in London, this was bound to be a contested territory. We decided to problematize the question. This led, thanks to the Biennale’s artistic director, Alya Sebti, to a fundamental question and the event’s title: Where are we now? Before we could understand our curatorial position in relation to the context in which we were working, we first had to test our own interpretative stance against the ideas of others. We didn’t have much time and needed to work quickly. I wasn’t particularly worried about the handful of Moroccan artists that I already knew, or the hundreds of others that would soon cross my path. No, it was the thousands of aspiring artists that could not (yet) gain access to the Moroccan art market, let alone the global one, who concerned me the most. What if, due to a lack of momentum and opportunities, the demand for contemporary Moroccan art couldn’t be met? International organisations often ask me to advise them about developments in this field and it is an issue that I worry about constantly.

And then there was the problem of identity. To whom do we ascribe ‘Moroccanness’?

HICHAM KHALIDI

The request to work with Moroccan artists also raised a number of issues that transcended the scope of a Biennale. It was, in fact, a political question. My response to Vanessa Branson was: “Change the system. If you would like more Moroccan artists in the show, you will need to make it political and find a way to confront politicians with the chronic lack of education in the country.” Our introductory sessions at public universities in Marrakech made one thing perfectly clear: the Moroccan education system is in dire straits.

And then there was the problem of identity. To whom do we ascribe ‘Moroccanness’? A similar problem arose when the contemporary artist Richard Bell restaged a version of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy (1972). The original encampment was established outside the Canberra Parliament by activists who were fighting for the rights of Aboriginal Australians. Bell’s version was shown at Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane in the context of an exhibition of works by so-called ‘indigenous artists’, with the presentations falling under the umbrella title of ‘contemporary indigenous art’. The participating artists were following the supposed ‘traditions’ to create a contemporary indigenous art, thereby challenging the definition of Australian art. When discussing the issue with Bell at a later date, the artist launched into a tirade against all forms of calling art ‘Australian’ or ‘indigenous’. His question was: why would a restaging of a political act be placed in relationship to the fraudulent production of what Australia could or might have been? This was guilt restaged: the white man’s guilt at having washed away the culture and livelihood of its First Nation peoples. And in a museum no less. Take another example. According to the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rabat, Moroccan art begins in 1914 with the work of the self-taught artist Mohammed Ben Ali Rbati. How national identities were constructed in the past, and the way they are formed today, always needs to be taken into consideration when operating within another context. Moroccan art did not start in 1914, of course, and it’s hard to imagine the adjectives ‘contemporary’ and ‘indigenous’ being used in the same sentence.

What if we looked at Morocco itself as a work of art? Would it be possible to view national identity as something plural and multiple, something that can be experienced and altered by the ‘other’?

HICHAM KHALIDI

When attempting to bridge the gap between the self and the other (as in another human being), one should be prepared to avoid, or at least postpone, judgment. How an artwork is perceived – as something plural, ambiguous or subjective – is largely dependent upon the on-going renegotiation of our personal experiences. This gave me an idea: what if we looked at Morocco itself as a work of art? Would it be possible to view national identity as something plural and multiple, something that can be experienced and altered by the ‘other’? Would I be able penetrate the sedimentary layers of the country’s history in the limited time available? After all, a biennale comes around every two years, with each subsequent curator free to make his or her own statement. This is why curating a biennale is so exciting: the time frame is so concentrated, and the experience so intense, that you merge with your subject matter. But above all else, I was searching for a way to translate the subjective and ambiguous characteristics of an artwork to a territory. Could we learn from the processes of making an artwork and project our findings onto the politics of a country? What can we learn from the fact that everyone views things differently? Can this be the basis of our politics? I struggled with these questions and, even though I knew there was something in them, it still felt as though I was comparing apples and oranges.

Furthermore, how could subjectivity help us to improve the educational system? How could it lead to a better sense of mutual understanding? How could it enhance our economy? For me, the answer lay in what Morocco already is: an accumulation of histories, emotions and perspectives. All of which is written large in the geography of Marrakech and its environs. In my mind’s eye, I sketched a geographical timeline. I saw people descend from the Atlas Mountains and follow the water flow, entering into the maze of Marrakech’s medina via one of the seven city gates, and exiting along one of the perfectly straight highways laid out by the architect Henri Prost and General Marshal Lyautey. The architect took account of the panorama when cutting his road: the majestic Atlas Mountains are visible on one side and, on the other, the routes to the sea. More often than not, the streets in the medina lead nowhere. This imbued our walks with a sense of suspense and adventure, not to mention surprise.

My timeline begins 10,000 years ago on the Yagour plain and ends in the industrial outskirts of the city. Now desolate, this was where olive oil refineries once flourished. The timeline includes the countless wars in which new religions, royalty, politics and positions battled for supremacy. After all, Morocco’s belief system is rooted in animist, Jewish, Christian and Muslim religions and the country has been inhabited, at various times, by Phoenicians, Amazigh, Europeans and Arabs. Like all lands, it is an amalgam of things and a construction of different beliefs, norms and cruelties. At the site in Marrakech where the Alaouite rulers built over the graveyards of their Saadian predecessors, for example, the conflicts of the past remain visible. This is Morocco: a sequence of events and a struggle between winners and losers. But, as my mental timeline evolved, it also came to stand for the feelings, wishes, perspectives and projections of the people themselves. It wasn’t only an historical timeline, but one that took account of the future. It was geography and time merged; it stood for the country itself. But above all else, there were no losers. Morocco belongs to everyone and is open to all those who want to be part of her.

A New Vision on Cultural Diplomacy

By Dirk De Wit

Culture is so much more than the global marketplace of supply and demand to which it is sometimes reduced in today’s global atmosphere. Culture is also the breeding ground for those complex identities and for negotiations between different places. A marketplace too can possess that quality of negotiation.

Like Hicham Khalidi, we ask ourselves what it means to be a ‘Flemish’ or an ‘Iranian’ artist? What is the role of art in Iran? How do people work in Iran and in Flanders? How can organisations work together? And why do we invite foreigners or accept invitations from abroad?

DIRK DE WIT (KUNSTENPUNT)

Intermediaries – such as Kunstenpunt/Flanders Arts Institute – and export offices that facilitate international relations generally realise them by establishing connections with the most important artistic hotspots or arts events worldwide, and by searching for new places and regions on diffrent continents where there are opportunities for development, (co-)production and presentation. Visitor programmes (inbound) or prospecting journeys (outbound) often take the shape of a trade mission. Supply and demand are matched on the basis of artistic affinities and the potential public interest. Participants are generally agents, programmers and curators who meet organisations and artists over the course of several days. A group of artists from Flanders travels to Lebanon for a working visit. A group of art professionals from Iran visits the Netherlands and Flanders.

Like Hicham Khalidi, we ask ourselves what it means to be a ‘Flemish’ or an ‘Iranian’ artist? What is the role of art in Iran? How do people work in Iran and in Flanders? How can organisations work together? And why do we invite foreigners or accept invitations from abroad? Aware of this market-oriented logic and of these divisions in terms of country and role in the production chain, Flanders Arts Institute has for some years been inviting artists in its international programmes, working with other foundations and agencies from Europe on visits to third countries through which national perspectives are broadened, and more attention is paid to the different contexts in which we work. Besides discovering production and performance opportunities, the parties learn much from one another.

The visitor programme Morocco Intersections organised by Lissa Kinnaer of Flanders Arts Institute in 2017 with curator Hicham Khalidi and Léa Morin of L’Atelier de l’Observatoire in Casablanca, is a good example. Sixteen art professionals from Belgium with different roles (artists, curators, writers, intermediaries) and from different cultural backgrounds took part in a six-day trip to Marrakech, Rabat and Casablanca. The first days felt quite strange: ‘we’ were visiting ‘them’. They explained their activities to us and we asked questions and tried to understand. During the third and fourth day, the group from Belgium called with the participants at the Madrassa workshop that was taking place in Casablanca, with curators from Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria and Palestine. Participants visited Casablanca in small groups, having been given a short research assignment to get to know the city’s hidden histories through discussions and recordings. The ‘we’ and ‘they’ dichotomy was cracked wide open: the curator’s observational gaze on art in another society made way for a sense of belonging to the city. Most participants wrote down their experiences in consistent essays from which it appears that the visit yielded more than just a list of artists and organisations with which one would one day like to undertake something.

Diplomatic delegations and cultural institutes base abroad could mean more if they turned their attention to the place where they find themselves, its needs and opportunities, and what the homeland can contribute in that regard.

Besides the market-oriented approach during visitor programmes, fairs and showcase festivals, intermediaries also need to develop other formats: focus on context and learning through longer stays (at least two weeks), working temporarily in an organisation, creating opportunities for artists to create on the spot with local artists, mixed groups and reciprocity on all levels.

Secondly, we ask ourselves the question how policy can support the role of culture in this transnational public space?

There is need in this space for a cultural policy that can go beyond the frames of the nation states or regions which support initiatives taken by their own inhabitants or organisations. There is also a need to broaden the frames of Europe which are mainly focused on internal European collaboration. Not only as an answer to artists who are becoming increasingly mobile and are increasingly difficult to categorise in a single country or region, but also to make use to the fullest of the potential of culture as a negotiation between various places and citizens.

Some countries and regions adapt their policy instruments to these new realities, within the frames of the nation state, it is true. As such, support for the national and international work of artists and organisations, which is increasingly interwoven in societies that are increasingly diverse, is better integrated. They are open to applicants who live and/or work there, regardless of their nationality. Other countries fold back in on themselves and celebrate the national culture as a protection against foreign influences.

Moreover, many countries and regions also have at their disposal instruments abroad in the form of cultural departments within diplomatic delegations or cultural institutes. They ensure the promotion of their country/region and facilitate collaboration between countries on a bilateral basis. These delegations could mean more if they turned their attention to the place where they find themselves, its needs and opportunities, and what the homeland can contribute in that regard. Such a new approach to cultural diplomacy offers points of contact for more collaboration among those delegations in a particular country, about how culture can assume its role as a developer of civil society at that well-determined place.

This supposes that, besides defending the interests of the country that one represents, one also believes in a higher interest, namely the role of culture in a civil society that we can describe as a transnational civil space. For instance, MORE EUROPE – External cultural relations is a public-private composed of British Council, Institut français, Goethe Institut, European Cultural Foundation and Stiftung Mercator, whose objective is to highlight and reinforce the role of culture in the European Union’s external relations. The Institut français and the Goethe Institut share the same building in Ramallah. The British Council, Institut français, Goethe Institut and other cultural institutes work closely together in Turkey, Tunisia and Morocco, setting up joint programmes that they develop alongside their own programmes. That collaboration has encouraged Europe to launch specific programmes for specific countries, like Tfanen for Tunisia. These partnerships and visions on cultural diplomacy form pilots that inspire countries and regions in their own policy vision. Eunic Global, the network of European cultural institutes, advocates this vision of cultural diplomacy and encourages collaboration among its members. Europe’s cultural policy can also be opened up to include the promotion of democracy and civil society through cultural collaboration, both within Europe and in its foreign policy towards third countries. In 2016 a start was made for a new strategy.

New forms of cultural diplomacy, based on civil society values and on collaboration between member states are in full development and have potential for the further development of civil society through culture.