Round table: Another Europe, More Europe

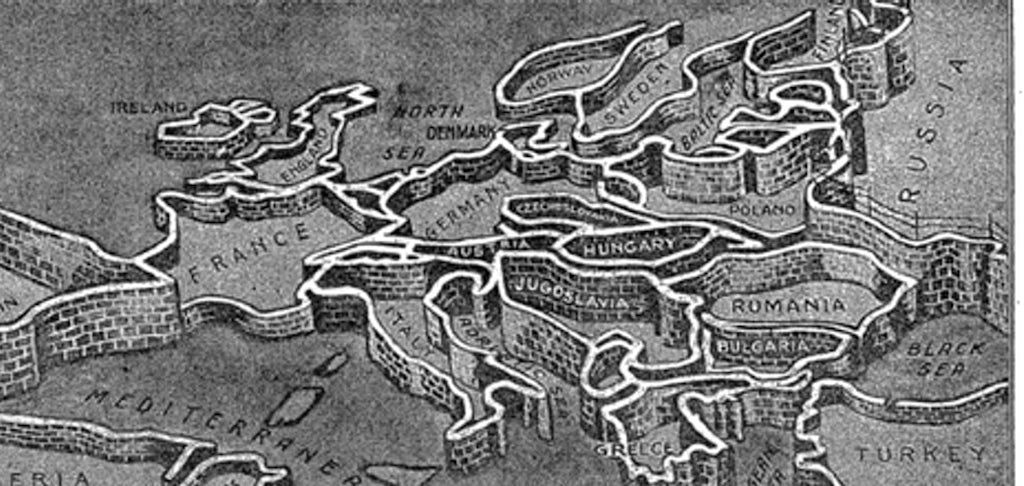

Imaginary walls in Europe (c) New York Times, 1926

Contributions by Flanders Arts Institute, European Culture Foundation, Bunker, Balkan Express & Budapest Observatory

How can we collaborate differently within a changing Europe and from what set of values do you start out? What processes do you set up to understand one another’s context and to be open to artists and places that receive less attention internationally? From what vision on mutual solidarity? What financing mechanisms can support this approach? How can cultural diplomacy build bridges and stand under the sign of exchange?

Flanders Arts Institute organized a round-table discussion on 27th of February 2017 on artistic collaboration within Europe, tackling these different questions. About 70 participants attended the round table: artists, curators and programmers, organisations, cultural institutions and foundations and policy makers from Belgium, other European countries and the EU.

Another Europe: 15 years of European Culture Foundation-projects and bottom-up capacity building in the EU and its neighbouring countries

Philip Dietachmair (European Culture Foundation ECF) and Milica Ilic (ONDA) have a lot of experience with exchange projects that bet on prospection, capacity building, organisation development and intercultural collaboration. They edited together the book Another Europe (2015) which provides an overview of 15 years of ECF projects in Eastern Europe and the EU’s neighbouring countries. ECF looks beyond the EU borders, embracing the countries that touch the EU to the east and to the south, believing that our culture can be shared beyond the classical borders.

‘In the late 1990s we were pioneers’, Dietachmair explained, ‘but in the meantime, the EU has devoted some attention to culture in its foreign policy. You can see that as an effect of slow, bottom-up work by local initiatives in difficult circumstances’.

‘How did it happen? In the late 1990s a whole process was set up, although it wasn’t clear at the time what this process would look like. Via a call for projects, ECF traced a whole bundle of interesting initiatives in Europe’s neighbouring countries. When we saw the conditions in which people had to work, we focused heavily on capacity building via training programmes. The next step: you see that there are suddenly a lot of interesting initiatives in the region, which suddenly also start networking and working together. There was no cultural policy context, so then we focused on advocacy: these transnational networks of grass-roots initiatives have developed a lot of clout. Thanks to their reinforced position they can really weigh in on policy development.’

From the start, it has not been about the East learning from the West. It has been about developing a way of working that is really fully suited to the local circumstances.

Milica Illic

‘There is a red thread in all the projects that we supported’, says Milica Ilic. ‘To start with: they all come from the independent sector, not from public institutions. There is talk in the whole region of the ‘Great Divide’, the gap between the institutional scene (which is subsidised, and recognised by the state machinery) and the independent scene (very vulnerable, precarious, and without any long-term prospects of subsidisation). ECF-backed projects function fully independently. You then see a number of recurrent elements. To begin with there is the ambition to rethink “the system” and to develop radically new models to create and disseminate culture. There is also the freedom not to be limited in this by the existing practice in institutions, but to create new places to set up new institutions to give fundamental ideas a place. There is an interesting example in Zagreb, called Pogon. That is a place that allows you to step outside the binary thought of public versus private. In the book you can also read an interview with Marek Adamov on how they developed their work model, entirely suited to the needs and possibilities in a local environment. Adamov says that their work is less focused on developing artistic content themselves, but especially on creating a meeting space.’

‘That type of reflection can be very instructive for venues in the West. You not only reflect on what you programme, but especially on how you work. Your organisation must be in tune with the values you stand for. This is a red line in all the stories in the book. And it is also important for ECF. It is central to their capacity-building programmes. From the start, it has not been about the East learning from the West. It has been about developing a way of working that is really fully suited to the local circumstances, which can vary strongly. All projects in the book demand a deep understanding” of local situations.’

‘Another red thread in all stories is social engagement. It is important to be clear about how this works. It is not about lowering the bar artistically. In the West you often see a gap between artistic work and sociocultural work. In the South and East that distinction is a lot less clear. It is precisely in sociocultural environments that you find the work that is artistically most incisive. Artistic work is also heavily value-driven. That is why there is a lot of interest in connections with other value-bound sectors, such as environmentalism.’

‘Teo Celakoski, the intellectual force behind this process in Croatia, is someone who also inspired a lot of other initiatives in the Balkans. Marek Adamov is just as animated. His standpoint is that you can talk to everyone, conservative or progressive. There is always a shared interest, or a common idea as regards solutions. I agree with him that you need a dialogue with the institutional framework. At the same time I want to go further. The West should also engage in this dialogue, but no longer from a Eurocentric perspective, and with a more open spirit and greater appreciation for what is happening in the region.’

Debate

Chris Keulemans (CK): “The book Another Europe builds on the believe that art and culture are essential for democratic processes and intercultural dialogue in all European countries. The independent scene of artists and platforms have an impact on society being a change maker. This believe is highly contrasted with the Europe of today, in which these values are suddenly under pressure in all countries by populism and nationalism. What happened with fifteen years of capacity building in Eastern and Southern Europe?”

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Dessislava Dimova (DD): “The experience of the past 20 years has shown that it is difficult to function outside the existing institutions. It has become very difficult for the independent scene to continue working. It is good to see that there are initiatives that are being picked up and developed, but from our perspective it seems utopian. It would be interesting if you could reinforce the ties with the existing institutions. What is the experience in this regard?”

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Presentation of the independent art organization Bunker (Ljubljana, SLO)

Nevenka Koprivsek – artistic director of Bunker – presents the organization:

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Presentation of the Balkan Express Network

Balkan Express is a platform that connects people interested in collaboration in and with the Balkans involved in contemporary art and complementary socially engaged practices. Balkan Express is a platform for reflection on the new roles of contemporary art in a changing political and social environment. It builds new relations; encourages sharing and cooperation and contributes to the recognition of contemporary arts in the Balkans and wider.

Nevenka Koprivsek (NK): ‘What really boosted our development is the collaboration in the Balkans region. When we set up Balkan Express, we were already well aware of what was happening in Brussels or Paris. But we knew very little about what our neighbours in the region were doing. That is the reason why we set up the Balkan Express network. Balkan Express gathers partners from the region who want to collaborate transnationally around socially engaged artistic practices. By now it has grown into something really big, but it still works very informally. In June we are having a meeting in Ljubljana – to which, by the way, you are cordially invited.’

Milica Illic (MI): ‘In order to contextualise the origin of Balkan Express, you need to have a good grasp of the working conditions in the independent sector in the region. There is a lot of precariousness, and so people are constantly busy creating the conditions of possibility for a next project. You really dash from one to the next. It is precisely for this reason that the network has always tried to create the conditions (time and space) for a fundamental reflection about projects and work conditions. That’s the point: to establish moments to talk about common ground, and to create openings for something new.’

NK: ‘Today there is talk of exhaustion. The conditions have become really difficult. Our staff has decreased by a quarter, and we have to work harder. We really are on the edge of precariousness and exhaustion. We have some experience with this. But today the transfer of experience is important – “how to teach fighting”. We have to pass on to a new generation our competences and skills in terms of survival.’

MI: ‘There is a lack of understanding and knowledge about who does what. But even more so, there are a lot of deeply rooted prejudices with regard to the region. We really have to name them, because they stand in the way of genuine collaboration. The work is always too this, or not enough that: too exotic, or not exotic enough, or not contemporary enough. Nothing is ever good enough. There are a lot of prejudices from the centre of power.’

Philip Dietachmair (PD): ‘That’s right, but that centre of power is also changing. That is something we are learning through our experiences in the context of the Tandem programmes. Work conditions in the north of England are just as precarious as those in the Balkans. The collaboration today happens on a more equal footing. That is precisely why interest is growing in exchange about possible innovative work models.’

Debate

Felix De Clerck (Kunstenpunt/Flanders Arts Institute): ‘What is meaningful collaboration?’

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Question by Chris Keulemans on misunderstanding between programmers/curators in the West and artistic work which is produced in Balkans and Eastern Europe:

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Question on how to end prejudice and the role of intermediary organizations like ONDA:

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Presentation of The Budapest Observatory

Peter Inkei: ‘The Budapest Observatory was founded 18 years ago. We are an observatory, which is to say that we observe. We observe Eastern Europe. By that we mean the former communist countries. Is this sufficient as a communal identity? What do we have in common? What is our shared heritage? In the beginning, such a thing as an ‘independent artist’ was new to us. Besides: most of our countries are nation states which, when they left the Ottoman Empire, became embroiled in a complex process of nation-building. In one way or another, that undigested idea of nation-building is still relevant for our countries. Something else: lagging behind. There is this idea that we are less successful than the West, that we are lagging behind. Not only economically, but in general. Only a select elite, which was also somewhat isolated, the urban middle class, looked ahead. Their relation with the lower classes is then again typical. It is the opposite of what Dickens wrote about nineteenth-century England. When you read Dickens, you see great respect for the working class. They are called Mister or Miss. In our corner of the world, people look down on the working class. At the same time there is a sort of folk exoticism. It is a source of pride, but it is also a danger. You run the risk of conforming to a presupposed idea about tradition.’

What do we have in common? What is our shared heritage?

‘We have a project going at the Budapest Observatory called the Eurobarometer. It shows that Eastern European countries have an attitude to art and culture that is different from the West. For instance, people go to the cinema a lot less than in the West. If it is about what the EU means to you, then there are only a few people in the East who saw cultural diversity as the binding agent of the European project. How we should explain that is unclear. But what is clear is that attitudes differ in the East and the West of Europe.’

‘Perhaps it has to do with the different forms of idealism that were propagated in the East and the West after World War II. The values were different, but in both regions you can talk of hierarchical paternalism. Everywhere the leaders knew what was good for the people, and the population accepted that. Today things have changed completely. There are so many different lifestyles and subcultures, and there is the power of social media. As a result, that kind of top-down influencing is now outdated. You see what happens when a leader emerges that simply agrees with the people – the ‘deplorables’, in the words of Hillary Clinton – in their primary feelings. Certainly in the East there is a vast breeding ground for frustration, for jealousy. The idea that going back to a former national glory or to imaginary communities can be an answer to social challenges is the stuff of dreams or hopes.’

We have a project going at the Budapest Observatory called the Eurobarometer. It shows that Eastern European countries have an attitude to art and culture that is different from the West.

Another project of the Budapest Observatory is the Cultural Policy Barometer: ‘We collected 27 statements about art and culture, about what the most acute issues are at present, and asked cultural experts what they find important and what bothers them. There are significant differences between the answers from the East and the West. Colleagues from the West pay more attention to the social dimension of art and culture. In the West, the social meaning of art was evoked more often as an important challenge. Why was this acknowledged less in the East? Perhaps because work conditions are more precarious than in the West? Another issue where differences were more pronounced: for Western respondents, the decreasing local financing of culture was really a very big challenge. In the East this was felt less as a problem. The biggest problem of the Eastern European respondents was then again: the all too direct interference of policy-makers in subsidising. There was widespread agreement in one area: that there is not enough interest among policy-makers for art and culture.’

‘A lot of people see government spending on the arts as an important indicator of the flourishing of culture in a country. But that’s not true. In Hungary, a lot of money is still spent on culture. What matters is how that money is spent. The age-old dilemma – is the value of art intrinsic or instrumental? – has perhaps become obsolete. Art is always instrumental: it prepares us all to deal with the legacies from the past, to handle a changing world. We have to think about Europe as a metaphor, as a symbol. Not for institutions, but as a symbol for liberal democracy. We have to propagate that as a value, so that the partners in the cultural field can connect to that.’

A lot of people see government spending on the arts as an important indicator of the flourishing of culture in a country. But that’s not true. In Hungary, a lot of money is still spent on culture. What matters is how that money is spent.

About the contributors

Moderator Chris Keulemans

The debate is moderated by Chris Keulemans (Tunis, 1960) who was founder and artistic director of the Tolhuistuin until 2014. He grew up, among other places, in Baghdad, Iraq. In 1984, he founded the literary bookshop Perdu in Amsterdam. During the nineties, he worked at De Balie, Centre for Culture and Politics in Amsterdam, first as a curator, later as director.

Keulemans has published books, fiction and nonfiction, and has published numerous articles on art, social movements, migration, music, cinema and war for national newspapers. He traveled extensively to study art after crisis in cities such as Beirut, Jakarta, Algiers, Prishtina, Sarajevo, Tirana, New York, Sofia, New Orleans, Belgrade and Ramallah, where he visited many talented artists.

Philip Dietachmair

Philipp Dietachmair is Programme Manager with the European Cultural Foundation (ECF) in Amsterdam. Responsible for the foundation’s EU Neighbourhood Programme and Tandem Cultural Managers Exchange. He develops and manages long-term cultural policy- and capacity development initiatives for the cultural sector in Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Turkey, the South-East Mediterranean, Russia and the Western Balkans. From 1999 to 2001 he coordinated higher education development projects and organized cultural events in Sarajevo, Bosnia–Herzegovina for World University Service (WUS) Austria. Next to his work for ECF Philipp Dietachmair did PhD research studies in Cultural Entrepreneurship at the University of Utrecht.

Milica Ilic

Milica Ilic is part of the pool of in-house experts of the French office for contemporary performing arts circulation (ONDA). She is companying and advising French performing arts professionals in the circulation of contemporary performing arts work and encouraging the internationalisation of the French performing arts scene. She is developing and implementing Onda’s international projects and international partnership development. Milica Illic is author and co-author of several research studies in particular within the field of international cultural cooperation and arts and culture in South-East Europe and freelance coordinator of international and cross-cultural projects. She is collaborator to international cultural organisations and European networks managing subsidy applications, programme evaluations, strategic planning and project development. From 2006 till 2014, Milica Illic was head of communication and administration of IETM.

Nevenka Koprivsek

Nevenka Koprivsek was trained at Ecole Internationale de Theatre Jacques Lecoq. She started her professional career as actress than theatre director. She was artistic of Glej theatre 1989 until 1997, when she has established a new independent organization BUNKER and with it Mladi Levi International Festival and since then acted as the company’s artistic director. Since 2004 Bunker is also in charge of Stara elektrarna, an old power plant converted into performing arts center.

Nevenka was involved or co-founder of many international networks and exchange projects. Occasionally she is writing, lecturing and advising on different issues of programming and cultural policy. She is also certified practitioner and teacher of Feldenkrais method of awareness through movement.

In 2003, the City of Ljubljana gave Nevenka Koprivšek a major municipal award for special achievements in culture and in 2011 she has been honored by the Government of France as a Chevalier and in 2015 as Officier d’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

Footage shot by Pieter Deprez