Reflections on Masculinity

About a year ago, Hugo Mega, a circus artist, coach and Imagery Therapist, reached out to Engagement Arts to talk about organising a space where men* could gather around the topic of masculinity. He spoke about a project dedicated to supporting men in getting more in touch with their masculinity and understanding what it means to be connected as men in a patriachal society from a therapeutic, transformative and feminist perspective.

Engagement, an artist-led movement tackling sexual harassment, sexism and abuse of power in the Belgian arts field, was immediately interested in the proposal. Kevin Fay, a performing artist researching how language operates in and on the body in terms of gender identity and expression, joined the conversation.

Engagement believes that feminism is about, for and happens with people of all genders, including men. Or, as bell hooks writes in The Will to Change – Men, Masculinity and Love : ‘Failure to examine the victimization of men keeps us from understanding maleness, from uncovering the space of connection that might lead more men to seek feminist transformation.’ Inspired by hooks’ thinking, Engagement started to exchange ideas with Hugo and Kevin.

By now, more than 30 Circles on Masculine Identities have been organised in RoSa, Kunsthal Gent and Beursschouwburg. During periods of Covid 19-restrictions, the circles have continued online. In the fall, Kevin received a grant by the Flemish Government to offer online performative reading circles that focus on feminist literature and the subject of masculinity. Time for Ilse Ghekiere – coordinator of Engagement – to sit down with Hugo and Kevin and take a moment to reflect.

* We are aware that ‘men’ is a binary term and might exclude a wide rage of gender identities. However, we hope that anyone feels welcome to converse about a world that is still dominated by binary logics.

Can you tell us a little more about how your projects started?

Hugo: “After spending a long time “working on” and coming to terms with my feminine side (or what I considered my feminine energy, aspects and qualities), I realised that being a man was something I’ve always been expected to be. Born a cisgender male, I did not know or understand what my masculine side was or what it could become. At some point, it became clear to me that I wanted to work with other men on the topic of masculinity. But this revelation was terrifying as I didn’t feel comfortable around other men.”

“Two years later, during a yoga festival in Bali, I had the opportunity to participate in an amazing men’s circle with about 40 men of all ages and backgrounds. By then, I had done a lot of healing work on my own masculine energy, and I was feeling at peace with the man I was. In that circle, I was able to witness, listen, and understand men in a way that was new to me. Regardless of their experience, circumstance or sexual orientation, these men yearned for deeper connection to themselves, to other men, to their fathers, and to be different men within a patriarchal society.”

“Well, this blew my mind and confirmed what I suspected. This was a decisive experience, and when I returned to Belgium, less than a month later, Male Identities was born, and I was hosting my first men’s circle with the support of Engagement Arts.”

Kevin: “In a way, work on my project began when I arrived in Belgium in 2016. I moved in August that year, and with the election of Donald Trump as president that November, I was devastated, sad, terrified, confused. Other people I know felt these ways, too, and now, despite glimmers of hope, we are in a volatile time.”

“Elections aside, however, because I grew up near Washington, D.C. as a white man in a certain economic class, at private, elite schools, I know how men are bred to be in the United States, and as a person who cannot identify with the patriarchal powers that be, I recognized in a profound, personal way in 2016 that I have to figure out how I became who I am and how I relate to others now.”

“Thankfully, while I was thinking this way, I met you (Ilse Ghekiere, coordinator of Engagement) about some editing work. Because of her, I followed some meetings with Engagement, and I started on the work of deconstructing patriarchy in me personally.”

“Then, with the confirmation hearings for Brett Kavanaugh in 2018, things came to a head for me personally because Brett Kavanaugh went to an elite, private high school in Maryland that I know very well. I mean, I almost went there myself! Regardless, in following his confirmation hearings and learning about the violence he had wrought, I felt, somehow, like my understanding of the place I’d been raised exploded.

“When he was confirmed as a Supreme Court judge in spite of Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony, I was mortified. I still am. I’m ashamed of how toxic, manipulative, dangerous men like him hold positions of unbelievable power in the government of my home country. It’s a lot, and it still is – especially right now.”

“Anyway, with all of this going on, I connected with Hugo about his ideas for Male Identities, and at the same time, my best female friend from high school assumed a role in counseling at the all boys’ Catholic school I attended in Washington, D.C. It seemed serendipitous because, all at once, I was connected with people who care about men and masculinity in ways that I do, too, and, in a special way, it’s because of these people that I’m doing what I’m doing right now.”

“I mean, it took planning, preparation, and reflection on my part, but with support from people who care and recommendations from people who know, I am on a path to research the intersections of feminism, masculinity, language, and the body. I was fortunate to receive a scholarship for this work from The Flemish Government, too.”

“Having that and support from RoSa vzw now, I’ve started offering online reading sessions called, ‘conversing with masculinity’. In sessions, we read excerpts from feminist texts and findings of masculinity researchers, and we use ideas I am developing to create poetry, lullabies, interviews, and drawings in an ongoing, collective effort to produce new kinds of knowing.”

“I always thought that feminism was a women’s fight (for equality). Becoming educated about it, I understood that feminism is much more complex and broad than I expected. I learned that as a man, there is a place for me in feminism.”

Hugo Mega.

What made it a necesity for you to focus on the topic masculinity from a feminist perspective?

Hugo: “It is important to understand that the patriarchal system is a system that encloses and imprisons men too. Understanding that I was not alone in my frustration and revulsion towards the “invisible”, normalized consequences of patriarchy was a really important shift in my perception, in my life.”

“I always thought that feminism was a women’s fight (for equality). Becoming educated about it, I understood that feminism is much more complex and broad than I expected. I learned that as a man, there is a place for me in feminism, and that I can contribute, even if in small ways (e.g. changing my perspective and my behaviours in oppressive systems), to the fight for everyone’s justice. It is this system that feminists are fighting.”

“When I understood this, I felt like I had been asleep, unconscious of what was conditioning me. I remember thinking, ‘Oh, wow! We all need to wake up to this reality!’. If this awakening had such a positive impact on me and my personal healing journey, on my masculinity, my relationship to my father and other men, then I couldn’t contain my desire to support others in the same process – thereby spreading this awareness and the hope that if more men do this work, how different can our future be?”

Kevin: “Honestly, I found myself talking about how I was feeling while I was working on a piece with Eleanor Bauer in Bochum, and a colleague named Emily Gale recommended readings and a film to me. She’s Canadian, but she said Michael Kimmel, Jackson Katz, and bell hooks would be good places for me to start looking for information about what was going on for me as a white, American man traumatized by the devolution of politics in his country.”

“Then, reading bell hooks’ The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, I was enthralled. I’d never read any of her work before, and I want to read everything I can find now. Her concision and clarity inspire me, and after finding her work, I knew I should look for more from feminist writers and thinkers – especially because bell hooks points to intersectional issues that stem from colonialist, capitalist, ableist, heterosexist, white supremacist patriarchy.”

“We are each embedded in systems that are so many things at once, and that made me feel like there’s a lot for me to (re)learn. From there, it’s been uplifting to discover perspectives I agree with even though I see more and more that things exist on a spectrum, and the work of change and justice takes time. Seeing that, I connect with the necessity of doing this work for the rest of my life.”

Why is it important to try and understand ‘masculinity’ in a different way, politically as well as socially?

Hugo: “In men and in masculinity, there seems to be a duality, which casts sensitivity or vulnerability in men as something to be hidden or kept private. At the same time, humans are more and more fragmented, divided, and compartmentalized by complex capitalist constructions and unattainable, idealized lifestyles glorified – even normalized – by social media now.”

“To give an example, in many heteronormative couples (regardless of sexual orientations in the couple), there can be a sense that ‘In my relationship, I can be my sensitive, vulnerable, goofy self, but when with friends, I have to portray this other more traditional, socially acceptable persona’. This duality generates a behavioural separation: ‘At home, I act one way, and in public, I act a different way.’ If we’re able to really bring everything into one reality, like ‘I can fully express my sense of humor and my vulnerabilities on a daily basis’, then that makes a different man – a different and whole person.”

“As humans, we are constructed by intricate patterns, which all root somewhere in our childhood. As we grow, we can transform and eventually dissolve these patterns through self-awareness and inquiry. This is one of the main missions of the circles – holding space for this work.”

“There are many adult men out there who struggle with their masculinity by refusing to mature. I’ve recently started exploring this through the Jungian perspective on boy psychology and man psychology. In the conversation about mature masculinity, there is an urgent need for men to do the work of understanding in what ways we’re triggered into immature behaviour patterns like the performative locker room talk of objectifying others or the choice to depend on unemployment fully and not look for a job or the ignorance of flaws you bring to your own intimate relations. Self-sabotaging, irresponsible talk or choices without any sense of accountability is usually how I categorize immature behaviour patterns.”

“More than anything, understanding one’s relation, as a man, to masculinity and to one’s own masculinity is to put in question the patriarchal system itself. To question in what ways am I repressing myself or aspects of me and in what ways am I oppressed or oppressing others is to understand personal behaviour patterns. I wonder how understanding one’s personal patriarchal construction would humanise or bring wholeness to our politicians and improve current political systems.”

“We are in the crises we face because too many men didn’t care to invest in strategies that prioritize the natural world, the historically oppressed, the colonized, and too many other people in our world who are not white, male, or privileged”.

Kevin Fay

Kevin: “We are in a moment of crisis worldwide. We arrived here, I think, because of how destructive, arrogant, ambitious, and violent men can be when they’re seeking power or advantage promised to them by patriarchal systems.”

“We are in the crises we face because too many men didn’t care to invest in or consider strategies or systems that prioritize or respect the natural world, the historically oppressed, the colonized, and too many other people in our world who are not white, male, or privileged by structures that uphold what bell hooks calls ‘white supremacist capitalist patriarchy’.”

“The areas of our lives affected by ‘masculinity’ as it is conventionally understood is overwhelming, but I think it’s also empowering. In “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House”, Audre Lorde writes about the significance of defining and empowering, and for me, naming and defining are necessary parts of the work – even if defining can present problems.”

“Perhaps in addressing problems with defining, we can discover strategies and tools for communicating better about the issues we face.”

Why linger around the status quo when much of the feminist and queer discourse attempts to go exactly beyond these gender binaries?

Kevin: “This is a great question. More and more, I’m angry about the status quo, but because there are so many people in the world who abide by it (and maybe don’t have the time, energy, and privilege required to question and attack it), I feel responsible for engaging with it.”

“That way, with language from the status quo as part of the conversation in feminist and queer discourse, the work I do can be inclusive in lots of directions. After all, as we see very well right now, none of us exist in a vacuum. We live together, and right now, we live together on a damaged planet that needs our attention.”

“We exist here, in a damaged place, in relation to one another and to nonhuman others, and while binaries are constructs that exclude people from the status quo, if we want to change the status quo and build worlds where diversity, justice, and inclusion hold their rightful places, then we have to understand our relationship to the status quo and engage with it in our work (i.e. fighting).”

Hugo, your work and interest seem to often have a ground in psychology. How do you perceive the correlation between activism and psychotherapy?

Hugo: “I often speak of ‘spiritual activism’. For me, choosing to heal ourselves is already an activist action. By healing ourselves, we generate more healing. When starting our own journey, we might notice that family and friends around us change, as if we’re shifting the perspective of the whole environment around us.”

“Healing of the self will also lead to more awareness in the activism we do. If we are unaware of the deep patterns that dictate how we act and react, then we are allowing our subconsciousness to take the lead. In other words, our baggage and the ‘wounded self’ leads our activist fight.”

“Maybe this explains why there is often so much violence within activist movements. If we haven’t dealt with our anger, then often we end up using our anger to react instead of respond to the need for change. But once we deal with our anger, we can seek change without needing to use anger as the motor, without falling back on defense mechanisms. Effective change is perhaps the change that comes from deep within, from our true, conscious self.”

You both work with and in the arts? Can you tell us something about your experiences in your respective art fields with regards to ‘masculinity’ and the expectations of being a man?

Kevin: “Well, my first job after school was in a ballet company, and there were a lot of expectations for me as a man there. First and foremost, attention to the way I looked was obscene. All company members were expected (but not required) to have gym memberships, and we were all taunted or teased about going to the gym if it ever looked like we didn’t”.

“As a man, expectations from the artistic staff were that I be hulking, burly, or even boxy (e.g. with broad, square shoulders). I couldn’t believe it. It was totally weird and arbitrary to me, and I simply did not comply. I mean, I worked hard when I was in the studio, and I went to the gym to do things that I enjoy doing there (e.g. stretching), but I wanted to be the way I already was, and I wanted to dance. Period.”

“I didn’t want to change the way my body looked, so I could appear a better (i.e. masculine or macho) partner or a more believable (i.e. hero) character on stage. It was crazy, and I’m sad to say my choices affected my casting. When I wasn’t everyone’s understudy, for instance, I was Mother Ginger in The Nutcracker.”

“If you don’t know, in that role, a man is sometimes cast to perform onstage in drag as a kind of “comedic relief”. I had fun because of who I am (and because I didn’t want to get fired), but it hurt because in playing that role, I perpetuated a shallow, flamboyant stereotype, and I didn’t need the technique I’d gained in school to do that.”

“I have to also say that when I was there, I was one of two gay men in a company of 20, and the heterosexual men in the company were all either dating or married to heterosexual women in the company. So, even if people were nice, and the job was good in terms of its social security and pay, it felt archaic, oppressive, and incestuous, somehow. Fortunately, the other gay man there became a great friend of mine.”

“Past that, there was a clear preference for men who excelled in ‘men’s steps’ (e.g. pirouettes a la seconde, multiples pirouettes, tours en l’air, beats, tricks, etc.), and even though that expectation for men to excel in men’s steps is pretty much in ballet everywhere, I never got into all that. So, after a year, I left to pursue work in contemporary dance.”

“In contemporary dance, all I can say is that I was aware of how being a male dancer in New York City meant I had easier access to job opportunities. I mean, there aren’t a lot of paying jobs there in the first place, and the competition to get them is fierce, but if you’re a man, then there is, sometimes, a demand because there are fewer of you available for work in the first place.”

“That said, my experience in New York was actually more that the same people got all of the jobs all of the time, and finding work is impossibly difficult there for all but maybe 10 people total.”

Hugo: “I started my artistic journey early on as a child in classical dance. Looking back now, I can understand how this was an experience of patriarchal and virile conditioning – both within the dance system I was studying and in my society, where choosing to pursue a dance career ‘dooms’ you to being among those who do not conform to the masculine standards typical of my Portuguese upbringing.”

“To be considered normal or socially acceptable, we must separate themselves, how they behave and look, from who they are and how they feel. I can’t help but wonder how different my experience in artistisc educational systems would have been if feminist education and awareness were parts of the curriculum.”

Hugo Mesa

“Ironically, what shocks me today is how binary classical dance can be: If you’re a man, then it’s ok to be sensitive and effeminate as long as you dance ‘like a man’. When moving from dance to study the circus arts, where artistic expression can be explored through different apparatuses and specialities, I was confronted again by the binary of masculine – feminine.”

“I ended up choosing to study everything that’s suspended in the air, which I learned quickly was, by some invisible norm, perceived as lyrical and therefore feminine, and that meant it was for women to explore. Having a strong dance background, it was in these specialities that I felt comfortable. It was literally like dancing in the air.”

“Having survived ballet’s conditioning and wanting to push on boundaries, I decided to move forward by specialising in aerial silks, something deemed a feminine speciality. It was an obvious choice for me – especially when I understood that in circus, you can earn respect and permission to exploit the apparatus of your choice when you can perform tricks or master a certain level of technique that proves not only your talent, but your expertise, courage, and strength.”

“This led me to push myself and my body beyond my limits. I consented to this to earn respect from and power or hierarchy over others, and the cost was separating myself from my body. I see this now as a clear consequence of virile constructions upheld by systems or traditions of comparison and competition. I see how my situation is only a variation on an old theme shown worldwide across artistic and other social and professional fields.”

“Men are split from their bodies at a very early age, perhaps from pre-teen ages, when we start to understand that to be considered normal or socially acceptable, we must separate ourselves, how I behave and how I look, from who I am and how I feel. I can’t help but wonder how different my experience in artistisc educational systems would have been if feminist education and awareness were parts of the curriculum at my schools.”

Practically and concretely, what makes a circle a circle? And how is the online reading group organised?

Hugo: “On a practical level, we are actually sitting in a circle, so that we can look at each other’s faces and eyes. Eye contact is important. What makes it a circle is also our ‘invisible contract’ of vulnerability: We all know that we’re together to talk about something that relates to ourselves and our private experiences.”

“People come to the circles because they’re seeking change, wanting to be heard and to connect. The circles should be a space where people feel safe to approach and address change. That’s what makes a circle a circle.”

“I facilitate the circles, but it’s really a group exchange. When the circles had to be organised online to comply with lockdown measures in the spring, they rapidly shifted in energy. I decided quickly to drop theory and tool-sharing, and I chose to engage with therapeutic imagery, instead.”

“So, each circle started with an imagery exercise and then focused on reactions to the exercise. (An imagery exercise is a short meditation on one’s interaction with subconscious images.) As a result of a relaxed, organic kind of structure, we began collectively giving each other tools since insights emerged naturally from sharing, from exchanging personal perspectives.”

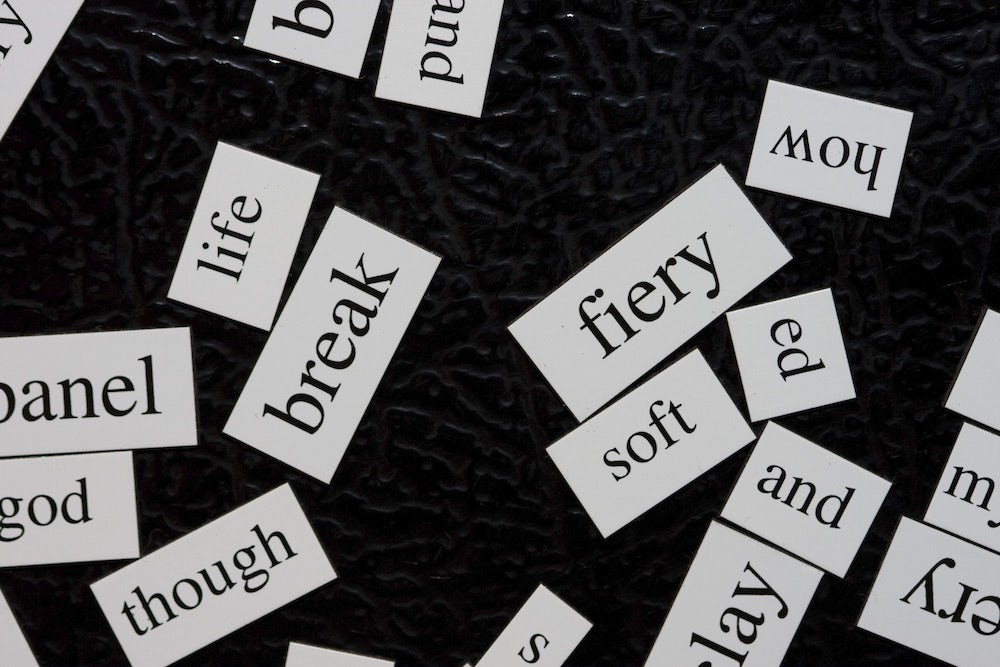

Kevin: “Officially speaking, I’ve only had one reading circle so far, and that was right before lockdown in March. While I hope that in person, group activities will take place again safely in the future, since the beginning of October, I’ve organized online reading sessions that follow pretty much the same structure: We join, we introduce ourselves, and then, we read and write.”

“While we’re reading, we write down words and phrases that evoke something immediately. We pay attention to our own first impressions, and the rule is just that you write something surprising, something strange, something violent, something beautiful, something hopeful, something confusing. It can be anything in the word list, really, but what you have in your word list has to come directly from the reading. There’s no personal notes or interpretations as part of the experience (though those are, of course, welcome and wonderful).”

After an hour or so of at least three different excerpts, we stop reading, and we play games with our word lists. Personally, I’m interested in distance and proximity in relation to words that relate to the body, so at this point, the games mostly have to do with going from a place of vastness, overwhelm, or overload and moving towards something concentrated, concise, or short in a way that invites gentle attention (e.g. haiku, drawing, lullaby, etc.).”

“There’s space for personal thoughts or feelings on the subjects broached in each of the sessions, but the focus for me is on looking for new kinds of knowledge between, behind, or through words we (learn to) use to articulate ideas like feminism, masculinity, and the patriarchy.”

As with all identities, masculinity can find itself on an intersectional axis. How would you take on, for example, a focus group on gay masculinity? What kind of work can there be done with masculinity within the gay male community?

Hugo: “As human beings, we all have a wound that needs to be healed. We just need to understand how to heal it. But it’s not like ‘We’re broken. We need fixing’. No. We are wounded, so we need time, attention and growth to heal.”

“There’s this book called The Velvet Rage by Alan Downs. In his book, Downs examines gay masculinity by defining three stages of dealing with shame. I feel really inspired by this book to look at masculinity and gay male identity in particular.”

“Downs goes really in depth on behavioural patterns: He has an extensive checklist that can easily be used as material for a circle. The author even suggests at the end of the book how to form and hold circles. When I read the book, I was really like ‘Yep, I know this guy, and I have been that guy.’. It was very easy for me to recognise gay masculinity.”

“To me, gay masculinity is in crisis. If masculinity on its own (regardless of included genders and sexual orientations) is in crisis, then in the gay male case, add to it the oppresion experienced by anyone internalizing shame towards homosexuality and hierarchical dynamics between men.”

“In her book, Le mythe de la virilité, Olivia Gazalé expands on the idea of hierarchies in patriarchy – starting from the misconception of man above woman and moving to be among men – with man being above anyone “less than” a man.”

“Basically, the closer to the feminine anyone is, the lower in hierarchy they will be seen by virile men (and the women who consent to virile, patriarchal constructions). In gay culture, I find more and more a parallel where virile, unattainable man is idolised – leading us as gay men to perpetuate the hierarchal system within gay realms and create destructive power dynamics based on limiting, archetypal labels like passive and active or top and bottom and ultimately placing gay men into groups that range from socially acceptable, “macho” standards to flamboyant, effeminate men who are not always welcome.”

“Personally, I am very excited about tackling this and learning from it because that’s the journey. I learn so much from circles on masculinity by being in them myself; together, with the participants. They keep on teaching me about masculinity and how to deal with it.”

Kevin: “Yes. It’s true. Masculinity finds itself on an intersectional axis, and I think right now about how me conducting reading circles in English in Belgium is a challenge. I mean, the English language is a colonizing force that’s relied on in international communications, and for me, there’s something masculine about that.”

“Obviously, I recognize the need for people in a globalized economy (i.e. world) to communicate in ways that allow for understanding, but when I think about how America came to be and how America behaves in international politics now, I have to acknowledge the arrogance in assuming people will speak English because, somehow, everyone should know and understand English.”

“For what it’s worth, I don’t ascribe to the logics that make English an official language for international communications, but as a student and not a fluent speaker of both Spanish and French, I know I’m a victim of the bias holding English in its place in our world.”

“Anyway, yes. Masculinity is on an intersectional axis, and removing it from that position to address the concerns of a specific group or category of people like ‘gay men’ is complicated. I don’t actually know if it’s possible. Is it? Maybe it is.”

“Research projects aside, language can be very gendered, and it can be wildly insufficient for communicating what we’re feeling and expressing as human beings. (Thank goodness we have art.)”

Kevin Fay

“I guess with reading circles, it depends on what’s triggered by the readings presented to a given group. Regardless, the interest for me in the work that I’m doing is in the spaces between what’s felt and what’s chosen. Indeed, in the movement between feeling and expressing, words are themselves predefined containers or constructions contaminated by binaries, and the idea for experimenting in the reading circles involves inviting people to deal with limited, predetermined options for language about bodies. Put concretely, I choose readings that determine the words we use in our games, and our collective whittling colors the conversations that we have.”

“Research projects aside, language can be very gendered, and it can be wildly insufficient for communicating what we’re feeling and expressing as human beings. (Thank goodness we have art.) Nevertheless, in my attempt to connect with feeling and expression in academic or intellectual exchanges that involve words from Audre Lorde, bell hooks, adrienne maree brown, Monique Wittig, Sara Ahmed, and others, I find it interesting and important to remember that we rely on words to communicate from the inside out even though words arrive in us from the outside.”

“And the outside, where we’re raised, plays a very big role in what language we use for what feelings. So, to answer your question, I would probably present any specific group or category of people interested in a reading circle with a selection of texts that purportedly apply to their demographic and see what comes up. After all, we are all always each in charge of how we use our words. Past that, if I’ve learned anything in this work so far, it is that we are all unique, and any work to be done in communities starts with individuals who care enough to interrogate their positions and relations.”

And for you, Kevin: How do you think about intersectionality in the research you’re doing?

Kevin: “Intersectionality excites me, too, but I have to say, I’m very aware of being a white, American man who received a scholarship from the Flemish government to study the topics that I’m studying, and I think of that as a privilege to acknowledge in and ofitself.”

“Would I be doing this work without financial support? Yes, but it would probably take a different rhythm and form. Either way, as I do what I’m doing, I find it very necessary to be in conversation with as many different people as possible. I won’t do research like this alone, and I don’t think I should (because an isolated, intellectual man invested in his own research of masculinity is perpetuating a stereotype and missing out on what feminism offers, isn’t he? I think so.).”

“I’m actually starting to think that the reading circle should become a network of conversation partners who offer one another empathy and space to question how language functions in and on bodies in conversations about gender identity and expression.”

“After all, I’m a sensitive person, and I think of what I’m doing as something sensitive, and that something could be powerful for others – especially when it’s happening one-on-one. I mean, questioning language in relation to me and my person in front of other people in a group who may be strangers while maybe also feeling self-conscious about my English language skills or my understanding of feminist theory and sociological research?”

“I think that’s a lot. I mean, for me, that’s a lot, and I’m doing it on purpose: Propose a variety of feminist voices in relation to voices of masculinity researchers, and use only fragments of excerpts from those voices to compose haiku, lullabies, drawings, or anonymous, one-on-one interviews quickly and perhaps imperfectly.”

“It’s an attempt to distill the essence of what’s going on for people when they’re listening to stimulating or provocative readings, but at the end of the day, intersectionality is huge, and while it’s necessary to keep that in mind, I’m going one step at a time, and I’m focusing my learning, my care, and my attention on the individuals in front of me and the words that move between us.”

More information

Circles on Male Identities by Hugo Mega:

- Website: maleidentities.com

- Instagram: @maleidentities

- Beursschouwburg: beursschouwburg.be/

Reading Circles Conversing with Masculinity by Kevin Fay:

- Facebook: fb.me/e/1HP836ZW8

- RoSa: rosavzw.be