Inherently social: interview with theatre company Ontroerend Goed on their international career and their platform ‘Big In Belgium’

The Ghent-based company Ontroerend Goed is celebrating its 15th anniversary this season. On this occasion, Filip Tielens and Flanders Arts Institute’s staff member Delphine Hesters have a conversation with artistic director Alexander Devriendt and core members Angelo Tijssens and Charlotte De Bruyne.

A compatible collective

Ontroerend Goed has travelled a long and exciting road since 2001. Are you still as close as you were then? How do you retain the same drive as back then?

Alexander Devriendt: We started out as a group of friends who organised festivals in Ghent. It’s difficult to give a name to what we were exactly, but a poets’ collective is probably what comes closest. David Bauwens, who is now the business manager and in charge of sales, used to be on stage with us at the time. Fifteen years ago, financial director Wim Smet and actor Joeri Smet were also up there with us. We’ve become a lot more professional since 2001, but I think we’re still the same group of friends as back then.

Over the years a number of members have gone their separate ways, but fortunately always on the best of terms. A few years ago Angelo Tijssens, Karolien De Bleser and Charlotte de Bruyne joined the artistic core.

Working with friends has the advantage that you can be a lot more critical towards one another. After all, you no longer have to doubt that friendship. If you work collectively, you can keep each other alert and so stay sharp.

Do you define Ontroerend Goed as a collective?

Devriendt: Certainly, but not one like those from the generation of Tg STAN or Maatschappij Discordia, where everything gets decided together. Ontroerend Goed is really a compatible collective, in which all core members reflect on the artistic decisions, but where the responsibility ultimately lies with me as director. But we will always put Ontroerend Goed forward as a collective rather than me as a director – even though that’s not always easy everywhere. In England, for instance, they’re mainly interested in the director or the writer of a play, while with Ontroerend Goed we want to avoid that cult of personality precisely. What we make is inherently social.

De Bruyne: In that regard, the riddle of individual longings is very important. Who has what ambitions? And what issues do we want to turn into theatre?

Devriendt: Working with friends has the advantage that you can be a lot more critical towards one another. After all, you no longer have to doubt that friendship. If you work collectively, you can keep each other alert and so stay sharp.

I think that on an artistic level we haven’t yet lost the drive of our early years. Ontroerend Goed developed out of youthful daring and rebellion against the system. We lost it for a while en route, but I think that we later recovered that spirit rapidly.

We hung the poster of that show crookedly up on the wall in our office as a warning for the future.

At what point did things go wrong then?

Devriendt: When, after five years of work, we first received a two-year structural subsidy, we made ‘Soap’, a theatre serial in several episodes. Before that we had done the ‘Porror Trilogy’, a bizarre mix of poetry, porn and horror. Weird stuff – we ourselves didn’t really know what it was. When in 2003 we were among the winners at Theater Aan Zee, it felt like a confirmation that what we had been doing was ‘theatre’. With the subsidies I suddenly also felt a greater sense of responsibility. With ‘Soap’ I tried too hard to make ‘real’ theatre and to conform to what people expected from me – or at least to what I thought people expected from a ‘theatre company’. While the strength of Ontroerend Goed lies precisely in the fact it always comes out of left field. ‘Soap’ was ultimately a big debacle. We hung the poster of that show crookedly up on the wall in our office as a warning for the future. (laughs)

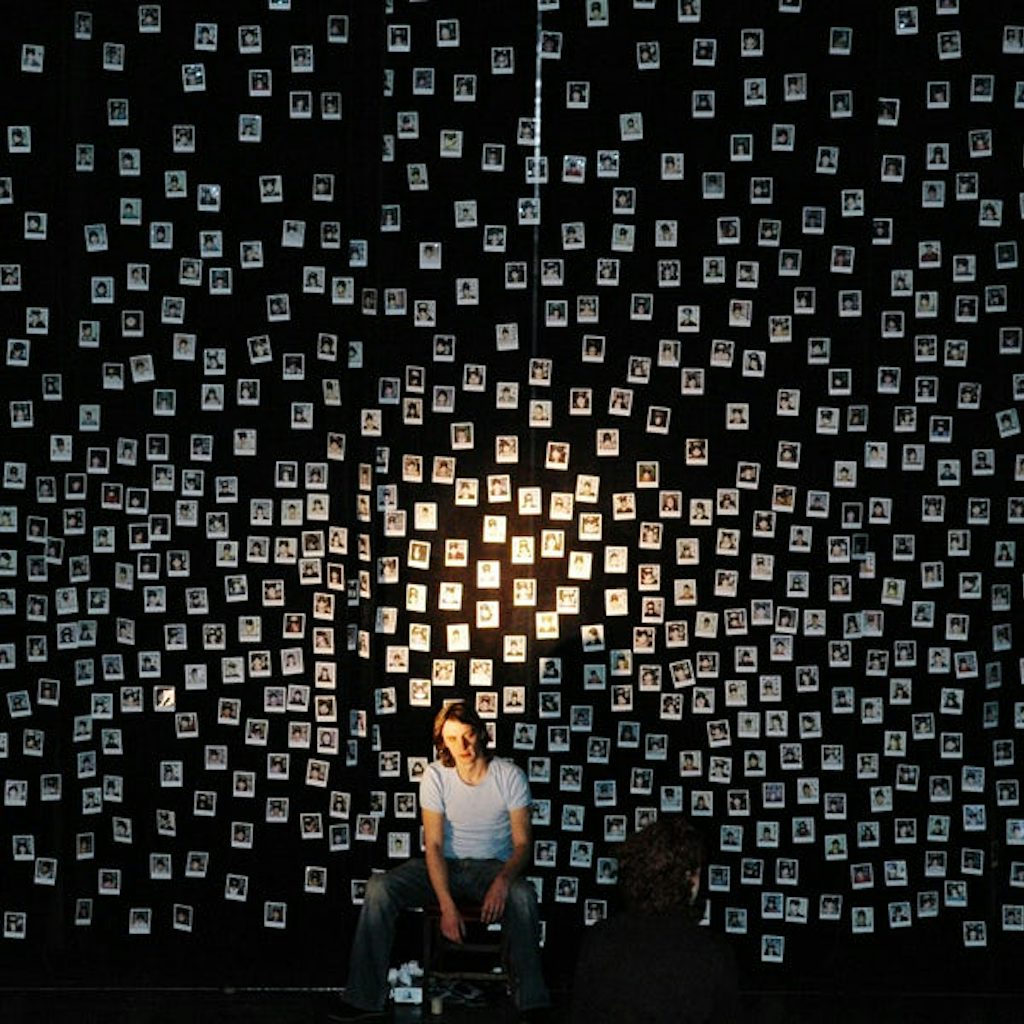

Fortunately at the time we were also experimenting with ‘The Smile Off Your Face’, a side project in which we took the audience on an individual tour in a wheelchair. You could say that after ‘Soap’ we fled abroad and that the success of ‘The Smile Off Your Face’ was kind of our salvation.

Flying high

There are programmers who really just want to book the hit show, but there are also those who are interested in you as a company. Some venues, like the Royal Theatre in Plymouth, were more interested in our subsequent show at the time than in ‘Once and For All’. That felt like a liberation.

Devriendt: After we had performed virtually everywhere in Flanders with ‘The Smile Off Your Face’, David had this crazy idea of taking the show to the Edinburgh Fringe. On the first day we played for two people. On the second day, for five people. And then after that there was this mad rush. We got one five-star review after another and were always sold out. We didn’t know what was happening to us! The following year we went to Edinburgh with ‘Once and For All’ . And again it was a huge hit with the public. Youth theatre for adults is hardly known, so in that respect it was as innovative as the individual theatre of ‘The Smile Off Your Face’. It led to a huge tour: we played 180 shows around the world over a two-year period. That was really crazy.

There are programmers who really just want to book the hit show, but there are also those who are interested in you as a company. Some venues, like the Royal Theatre in Plymouth, were more interested in our subsequent show at the time than in ‘Once and For All’. That felt like a liberation.

Tijssens: The Edinburgh Fringe proved to be our gateway to the rest of the world. It is thanks to this festival that we later also travelled to Canada, Australia and Hong Kong. In recent years we’ve also performed at the Off Festival in Avignon, which mainly serves as a gateway to the rest of France. Last summer we performed ‘Fight Night’ there and that has led to a solid tour across France over the coming years.

Wim Smet: Budgets in England and Australia are currently under considerable pressure. What’s more, Brexit is having an undesired side effect: the fall of the pound sterling means that payments we are waiting to receive are suddenly worth tens of thousands of euros less. For the time being, the budgets in France are still holding fast. That country is filling an increasingly important share in our tour schedule.

Repertoire

By touring so much internationally, your market is really big. That often results in very long runs per show. Your plays often remain on the repertoire for years.

De Bruyne: That can also help a show mature. At the premiere in Ghent, our show ‘Sirens’ really divided the audience. There were those who loved it and those who hated it. The press too was harsh. We weren’t ready for that back then. But at the same time you’re already aware that after this you’re going to be playing in Edinburgh and in Plymouth, and always before a new audience without any prior knowledge. So you know that there are other markets for your show and that you’re not only performing for a Flemish audience. ‘Sirens’ was acclaimed in the British press, with full-page analyses of the feminism in the show.

Every show will find its audience, especially since we have a large market internationally too. That awareness releases the pressure during the creation of a show.

Tijssens: With shows like ‘Fight Night’ and ‘A History of Everything’, you know that they can catch on worldwide. Democracy and politics are universal themes that everyone has to deal with. That means that people everywhere recognise themselves in ‘Fight Night’. In Hong Kong, for instance, they projected the Umbrella Movement onto our play, and elsewhere it was the Occupy movement. I often get asked how much of the text gets adapted from one venue to the next, while in fact I use the same text word for word, whether in Aalter, Sydney or Toronto. (laughs)

Devriendt: Other projects – such as ‘Sirens’ and ‘All That Is Wrong’ – are perhaps less suited to a large audience, but they also have fans in all the countries. Even if a play only catches on in a specific niche, you can still generate a large audience if you add up all those niches in all the different cities. Every show will find its audience, especially since we have a large market internationally too. That awareness releases the pressure during the creation of a show. Also, by having a lot of shows available, in discussions with programmers we can adapt our proposals to ensure that the right show finds the right slot. We don’t have to rely so much on the latest show.

All our actors are freelancers. There are 40 people who can perform ‘A Game of You’, in four languages. Per run we can then see what actors are available.

How do you choose the pieces that remain in the repertoire and those that don’t?

Devriendt: With a show like ‘Internal’, for instance, we felt that, in terms of one-on-one theatre, we created a stronger show with ‘A Game of You’, and so we decided to perform it less, even though several programmers preferred having the controversy of ‘Internal’ on their programmes. I wasn’t too happy with ‘Under The Influence’ either, a party performance that was a big hit in the Netherlands. And so we took those shows out of circulation. Another reason for stopping a show is the age of the players. Koba Ryckewaert had finished with ‘All That Is Wrong’ after a while. And you can’t keep ‘Once and For All’ in the repertoire forever because the adolescents will otherwise be in their twenties.

Tijssens: Other shows can tour for longer because we work with replacements. All our actors are freelancers, which means that we also respect the fact that they can have contracts for other projects. There are 40 people who can perform ‘A Game of You’, in four languages. Per run we can then see what actors are available. That’s the advantage of making rather conceptual plays: it isn’t so much about the personality of the performer. Actors who really want to have their own name stand out are not at the right address with Ontroerend Goed.

For our new show too, ‘£¥€$’, we are already taking this into account during the creative process. We are rehearsing the play with 14 actors, while only half of them perform in an evening. In addition, we’re making both a long and a short, cheaper version of the play, so that we can take the market into account early on already.

Devriendt: While other productions are tailor-made precisely for the actors. I couldn’t have done ‘All That Is Wrong’ with anyone but Koba. And when I was asked to make a remake of ‘Once and For All’ in London in the space of a month, I refused. I spent nine months working on the original play and that time was really necessary to discover the specific characteristics of the young people. In ‘World Without Us’ I was afraid that the agenda of actor Valentijn Dhaenens would be too full to be able to make it with him alone. But fortunately in terms of contents here too it made sense to invite a second actor to join. I couldn’t only tell a play about the end of the world from a male perspective, I thought. And so Karolien De Bleser alternates with Valentijn.

Tijssens: For our new show too, ‘£¥€$’, we are already taking this into account during the creative process. We are rehearsing the play with 14 actors, while only half of them perform in an evening. In addition, we’re making both a long and a short, cheaper version of the play, so that we can take the market into account early on already. By having so many shows in our repertoire and by anticipating during the creative process already, we can allow ourselves to release a new play only once a year, for which we have then reckoned in a long preparation time. While we tour with the actors in the most remote countries, Alexander can spend months in his room reading difficult books on a new subject. (laughs)

It may sound naive, but I don’t really believe in intellectual property. With the book we want to give readers tools so that they themselves can set to work with our plays. Compare it with the theatrical repertoire that is published. In our case, they are rather conceptual scripts.

Sharing is caring

For the past four years you have been sharing your international know-how with other companies via Big in Belgium, a curated part of the Edinburgh Fringe. How did that initiative come about? What does it bring you?

Devriendt: When Valentijn Dhaenens played there with his solo ‘Bigmouth’ soon after our first runs, he relied on the contacts of David Bauwens to lure the press and programmers to his show. It worked really well and that’s how we got the idea of doing that for other companies too. We share our whole address book which we built up over seven years. Even though some think we’re shooting ourselves in the foot in doing so. But everyone wins in the long run, I think.

Over the years David has become better at knowing what shows will go down well in Edinburgh and can tour abroad. In doing so he certainly doesn’t choose the most obvious plays. There is no formula by which to score quickly abroad. It remains a process of trial and error, but nevertheless David has developed quite an instinct for that kind of thing.

Tijssens: Neither does being selected for Big in Belgium mean that you’re guaranteed to launch internationally. It is at best the start of a conversation. But at the same time it has grown in those four years into a quality label, a hallmark. In 2016 three of the six shows of Big in Belgium were among the winners of the Total Theatre Awards. Out of a total of 3,000 productions at the Fringe, that’s an impressive number.

With ‘All Work and No Plays’, you released a book featuring blueprints of some shows, so that everyone can restage them. Besides that, in Hong Kong and Turkey you created new versions of ‘Fight Night’ and in Russia you made a remake of ‘A Game of You’ with a local cast. Why do you do that? Do you really attach so little importance to the intellectual property of your plays?

Devriendt: It may sound naive, but I don’t really believe in intellectual property. With the book we want to give readers tools so that they themselves can set to work with our plays. Compare it with the theatrical repertoire that is published. In our case, they are rather conceptual scripts. I always want to make theatre for as many people as possible. If this means that you’d better give up control over your own creations, then I find that rather exciting precisely.

Sometimes it’s also best to make a local remake rather than play somewhere yourself and surtitle your show. In particular, an intimate, individual and interactive play like ‘A Game of You’ works less well with a public that doesn’t speak good English. The language gap will be in the way of the experience and the involvement. Moreover I find it a greater challenge for myself to teach a play of ours to new people in Russia or Turkey than to go on tour with it ourselves.

Concept repertoire

Where do you get your inspiration? What is the starting point for a new show?

Devriendt: Ever since ‘Audience’, which dates from 2011, solid research in terms of content precedes all our shows. Non-fiction books about science and society inspire us more than fiction. I can really enjoy reading a good work of fiction, but in doing so I don’t feel the need to adapt it for the stage. A novel has often reached its ultimate form already, I find.

The blackboard on which Koba Ryckewaert writes down all her problems with the world in ‘All That Is Wrong’ functions as a point of reference for me. Every show that we made since then with Ontroerend Goed zooms in on one of the areas: ‘Sirens’ was about feminism, ‘Fight Night’ about democracy, our next show, ‘£¥€$’, about the economy, etc.

De Bruyne: That is also the reason why I wanted to join Ontroerend Goed. Our shows raise questions that keep me awake. When Trump gets elected president and that same evening I get to play ‘Fight Night’ in Canada, it feels like my way of reflecting on the world and of sharing this with an audience.

In doing so I hope that we can bring some beauty and hope with Ontroerend Goed. The world is getting increasingly pessimistic, and politicians are leaning further and further to the right. We’re currently living on a dark cloud. As an individual you often get the feeling that you don’t have much of an impact on the bigger picture. Your political voice makes no difference, so to speak. What you do for the climate seems meaningless, but it’s not. I hope that with our shows we can provide a beacon of light and prove that you’re not powerless as an individual.

That is also the reason why I wanted to join Ontroerend Goed. Our shows raise questions that keep me awake. When Trump gets elected president and that same evening I get to play ‘Fight Night’ in Canada, it feels like my way of reflecting on the world and of sharing this with an audience.

Is that why you often let the audience itself take control during your shows?

Tijssens: Indeed. When, as now with ‘£¥€$’, we’re making something about the economy, we won’t write a play in which four bankers are sitting in a café. We find it more interesting to let the public itself play a role as a banker and in that way to involve them in the theme.

Devriendt: The same goes for ‘Fight Night’. For a long time I’d had this idea that the public could vote someone off, but it remained shelved all that time. Until I began to feel frustrated about our political situation. How can a country like Belgium spend 541 days without a government? How is it possible that Bart De Wever, after taking part in the TV show ‘De Slimste Mens ter Wereld’, can become the most popular politician in the country? It’s only when form and content coincide that we decide to really make a show.