Nothing ventured nothing gained

(c) Anton Coene

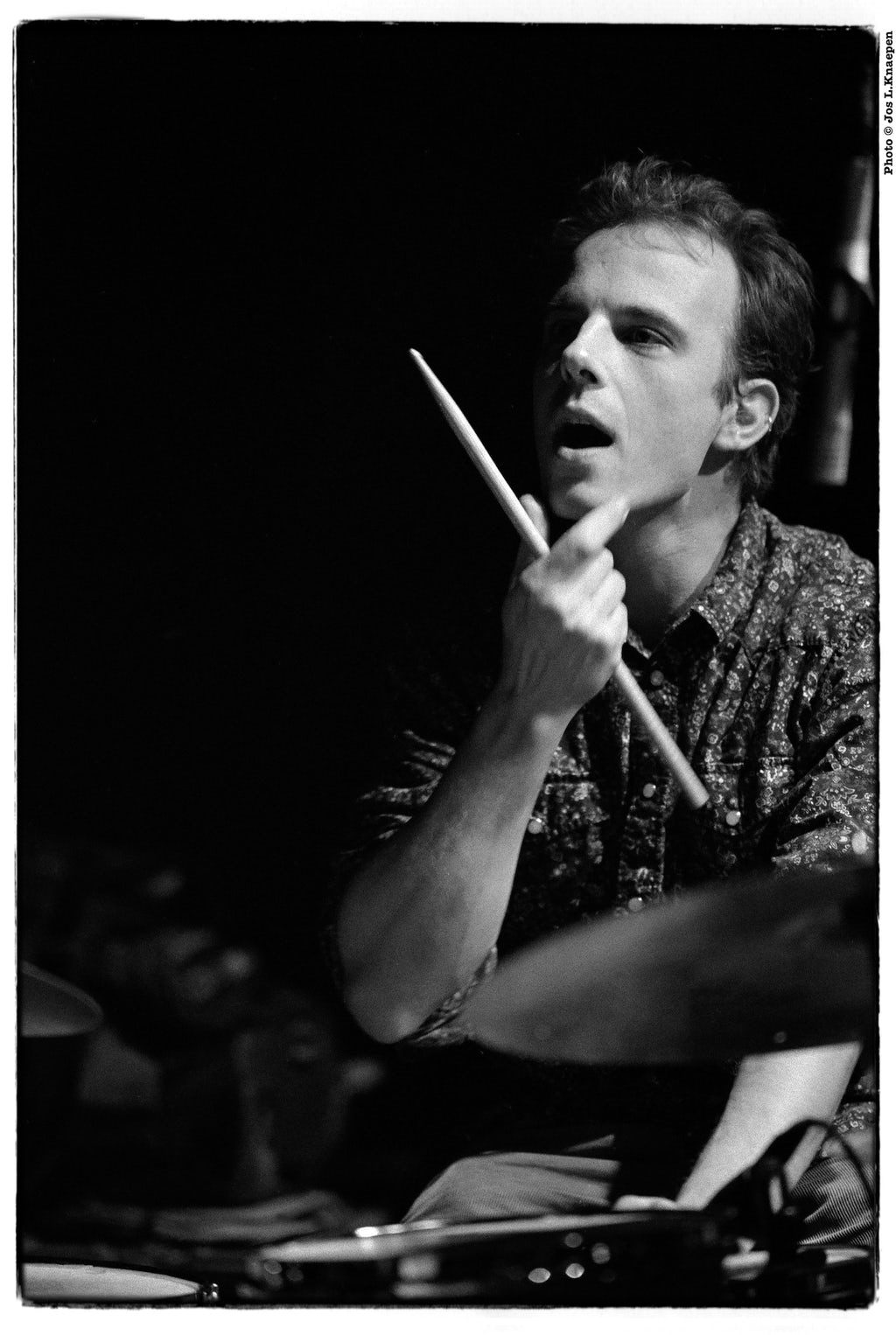

Since first picking up the drum sticks at the age of eight, Teun Verbruggen has had an impressive international career. As one of the most sought-after drummers in jazz and far beyond, he has performed with Alexi Tuomarila, Jef Neve, Melanie de Biasio and Toots Thielemans, to name but a few. Verbruggen is not only a welcome guest at live shows extending from Scandinavia, through Mexico and Australia, to Japan: The “international” is also intertwined in many other ways in his work as a musician. Take his latest project, Walter for example: a workshop for musicians, video makers, visual artists and the like in an old textile factory in Anderlecht. All of which makes him one of the ideal partners for our interview series following the analysis Have Love, Will Travel, published earlier this year by Flanders Arts Institute. Below, we find out what working internationally means for one of the most respected jazz drummers in Belgium.

You notice that the world soon becomes very small. New bands are constantly being put together, with people from totally different countries. For example: I just returned from a tour with a Norwegian, a Parisian, an Englishman and a New Yorker. We come together for a week to tour, and then each go our separate ways.

You’ve played with many different talented musicians throughout your career. How important is it for you to be active outside Belgium?

I’ve been playing abroad a lot, in many different bands, since 2001. To really pursue an international career – by which I don’t necessarily mean that you must become really famous, but rather that you play a lot abroad – you have to persevere. If you tour with only one band, your international career will stop if that group splits. And that doesn’t have to be a bad thing. But if you want to build up something in the long term, you have to maintain your contacts. I always make it a point to chat with the organisers of the performances I play abroad, and with the musicians in other groups. In this way you build a network on which you can fall back later. And it’s very important that you maintain and expand that network.

You must try to ensure that the dynamic within your network is one of give and take. Unlike in pop music, jazz musicians like me often organise concerts themselves. In this way I can do a return a favour to those who once booked one of my bands: by inviting them to come and play in Brussels, for example.

In this regard, it is perhaps easier to build connections in the jazz scene: if you’re a pop act, then it’s primarily the manager who develops his or her network. The musicians benefit from this only indirectly. If you play a concert with a number of musicians in Berlin, of course you will come into direct contact with them. Jazz musicians tend to be freelance musicians: we play in many groups. And thus you notice that the world soon becomes very small. New bands are constantly being put together, with people from totally different countries. For example: I just returned from a tour with a Norwegian, a Parisian, an Englishman and a New Yorker. We come together for a week to tour, and then each go our separate ways. One of these musicians even flew specially from Austin, Texas. And the following week he went to Chicago.

That’s a lot of travelling.

Yes, but that’s how it goes. I’ve also known periods in which I regularly flew to Mexico to play, and then flew on to Canada. I once even toured Canada with two bands at the same time: I played a concert one night in Vancouver with one band, the next evening a show in Montreal with the other group, then back to Vancouver to accompany the first band to the next gig.

Isn’t that extremely tiring?

Of course it is. But personally I get a kick out of it: it keeps me focused. My favourite thing is travelling alone and touring with different groups at the same time. I think it’s great to be alone on the plane, to play, and go somewhere else the next morning. But the hours of jet lag do accumulate.

Many of my friends have already warned me: ‘Teun, you’re going to pay for this one day, it’s inevitable!’ But they’ve been saying that for fifteen years, and I’m still on my feet. Last month I read somewhere that burnouts apparently arise mainly when you don’t like what you’re doing. If you are stuck in a situation that you want to leave, your stress limit would be a lot lower and you’ll burn out more quickly.

I actually just heard the opposite: that burnouts mainly occur in people who are very passionate about their job, and always want to do more and better. Eventually you can’t keep up. But maybe both are right?

It is indeed a double-edged sword. In any case, I notice that as I grow older, I’ve become a bit more relaxed in what I do. I used to go out quite often, drank quite a few beers after a performance, smoked a lot, and my diet was unhealthy. Nowadays I live reasonably straight: I try to eat healthy, exercise a lot and crawl into my bed on time. Which is possible: a concert usually finishes at 11 or 12 in the evening. It’s possible to simply go to bed right away. I’m not able to stay up late like I used to.

You may be taking a calmer approach to partying, but you’re still fully engaged in your work. Actually, you’re lucky to have that drive?

When I graduated, I had a much less of an entrepreneurial attitude. Only when someone called me did I spring into action. I immediately said ‘yes’ to each cool offer that was presented. I did have constant work, but mainly because people appreciated my energy on stage. Not so much because I was looking for it so hard. But I have to add: when I was young, there weren’t so many skilled jazz drummers. Now many good drummers from all over the country are finishing their studies. In our time there were a lot less. Today, young musicians are also much more on top of their business. They know much better where they want to go. In the beginning I just wanted to play with good musicians. I didn’t really have a plan.

But at a certain point I no longer felt comfortable being so dependent on what other people offered me. I noticed that I was constantly playing music that I liked, but it was not really my own thing. And then I realised that – if I really wanted to do my own thing artistically – I would have to take matters into my own hands.

From then on, I always looked for new challenges. That was difficult in the beginning. But gradually I became addicted to it: I started a label, founded several new bands, and even now – with Walter – a bunch of new collaborations have been added.

Usually these are projects that people think are totally impossible. And sometimes they are: it happens, for example, that you call a musician who has just decided not to accept any new projects. I recently encountered this with a guitarist. But sometimes the reverse happens: someone you look up to and whom you hardly dare to ask to collaborate on your project, suddenly joins. Which is why I always kept in touch with Mike Patton: he is really my hero, in many respects. I know him a bit because we once joined him on tour with Flat Earth Society and because I often play together with his bass player. I also always send him the new music I make, to which he always reacts very positively. And at one point I told him that I wouldn’t forgive myself if I never told him that I would really like to drum with him. He appreciated that and said he would keep it in mind. Of course you know that he plays with the best musicians in the world. But if you don’t say something, you’ll never know. It’s like meeting a beautiful woman: if you don’t talk to her, you’ll feel sorry afterwards.

A career is never ‘won’. A real ‘star’ does not actually exist.

Nothing ventured nothing gained.

Voilà. And that’s not easy. But nowadays I do it all the time. You have nothing to lose. So you might as well try. And sometimes you’re really amazed by what happens next. I recently experienced that with a trumpet player with whom I wanted to work for a long time. I had already asked him a few times, but something always came up: sometimes he had too much work, other times he was in the middle of a divorce or had to take care of his children. But I kept asking, every so often, without it becoming pushy. And after six years he finally said ‘yes’. The result: the two coolest records of my career!

And if people say ‘no’, you shouldn’t take it personally. Not if they do it correctly.

For many musicians, ‘international work’ today is still mainly export oriented: “Belgium is too small, we have to go abroad to expand our market”. But you work internationally in very different ways: by playing together with musicians from all over the world, by inviting them to Walter, by performing abroad, and so on.

I simply find it all incredibly fun to do. However, there’s a lot of hassle is involved as well: you have to call people all the time to keep your schedule on track. I spend at least four hours a day behind my desk. But I’m happy to include this part of the job. And I even think that I finally found the way of working that suits me best.. Having a manager doesn’t necessarily make things easier. Because even then you still have to keep pushing for things yourself. Your entourage thinks in a different way. And they don’t always have a network of musicians.

I certainly don’t want to say that management offices and booking agencies don’t have their place. But I think that organisers in the jazz world are still more inclined to work with musicians directly. Because many of these people hold their personal relations with musicians in high regard. For Wim Wabbes, for example, the personal contact with Marc Ribot was the motivation to continue in his job. He also works with management agencies, but without personal contact there will never be a long-term relationship. And I notice this myself: when I write to people personally, it comes across differently than if a manager does it for you.

Part of that will also have to do with the career you’ve built up so far and the professional development you went through. A similar request from a newly graduated jazz drummer probably has a higher chance of being ignored. Did you experience a moment when you gained momentum and suddenly were considered a professional?

A career in music always has ups and downs. But at times when I felt that less work was coming in, I tried to compensate by intensely looking for projects myself. I always made sure to keep myself busy.

But being busy doesn’t always mean being paid. Financially, my career has had even more ups and downs. When I played with Jef Neve, for example, I was paid very well. Since I no longer play with him, that translates into my bank account. But is my career going downhill because of it? I don’t think so. It was simply a very nice experience. And now other things take its place, which in turn have their value. I think the trick is to continually weigh things up for yourself during the course of your career.

How do you choose today which projects to accept and which not?

There is a generation full of young jazz talent that gets most of the attention and exposure. Naturally, most concert promoters want to book these young, hip bands. And that’s great for them. But as a musician who has greater difficulty gaining attention due to this, you have to take that into account. You then have to look for ways to deal with it: ‘how can I solve this? How can I continue to innovate?’ In fact I find it all quite challenging. There are people who get frustrated because of this. But that will get you nowhere. You simply have to keep moving and devise things that continue to give people a reason to book your band. No one wants to see a plain Jane or average Joe on stage. And fortunately, these young artists are there to keep us awake.

Even now you continue to reinvent yourself?

A career is never ‘won’. It can end in a snap. Even a world star like Madonna must continue to reinvent herself. Which is exactly the challenge. A real ‘star’ does not actually exist.

The difference of course is that the Madonnas and Justin Biebers of this world are surrounded by a team of people who come up with the ‘product’. And they have to present it. But most other musicians have to do it themselves. No one is going to take you by the hand.

And certainly not in the niche in which I work. Here, a manager would have to have a lot of motivation to work with a musician like me. You’re aiming for a niche audience within a small scene. It’s not easy to reach the right people. It’s a lot of work, with very little to show for it. For me, that’s okay: I do my own thing, and I also play in other people’s bands. So I don’t need to live off my own music.

Do you then accept these other projects purely for financial reasons?

No, I like all the projects I accept. There is no band that I don’t like playing with. But I don’t always have to be completely on board with the aesthetics of a band to like it. I can function perfectly in a band without the aesthetics of that band corresponding to mine.

My own projects usually involve a lot of musical research. And sometimes it happens that I listen to it five years later and ask myself: ‘Wow, what’s that all about?’ But output is not always the most important thing for me. A record is just a snapshot. I’m very proud of most of my records, but not all. But that’s not a problem. It’s good that I made them. You learn from it and move on. It’s all part of a bigger picture, of one great exploration of sounds and expression. It really is super fun that I’m able to spend my time doing what I like. Actually, I live a privileged life.

Long-haul flights have an ecological footprint that is actually not okay. So if you do something like that, you should make sure that the tour fits within a long-term vision. Firstly, make sure that it fits within your artistic story, and secondly that you give something back to the local community.

Do you incorporate (the results of) this musical exploration into your other projects afterwards?

I keep challenging myself, so I never get tired of what I do. Therefore I never feel that I’ve reached the end point with a band. So basically, I am a very loyal musician. I can’t quit a band. If I ever quit a band, it was probably because our paths happened to diverge, or because the band needed someone with a different style. But really saying ‘I quit’, that has not happened often. Which does not change the fact that sometimes you can play together with people for so long that you no longer reinforce one another. Maybe it’s then time for the band to play with a different drummer. But that doesn’t mean that the relationship will stop. In the case of Jef Neve, for example, the feeling was mutual: we both felt that we needed to do something fresh. Which is quite normal.

But I’ve been playing with most people since I started studying in 1994. That creates a bond of trust that only makes the music better. Over time, the whole will transcend the sum of the parts. And sometimes there’s a project of which I think: ‘I really could have done without that’. But because it belongs to the path that the band is following, I’m happy to go along with it.

That’s a very open vision.

Yes, but I wouldn’t be able to function if I refused everything that is not entirely my thing. I tried that once, and it didn’t work out well. When you play in a band like Flat Earth Society, you actually have to participate in everything, even though they work on a project basis. It’s all or nothing. Compare it to a trip you make with a bunch of friends. Suppose everyone goes for a walk on the third day, but you don’t join: then there’s a piece of that journey that you haven’t experienced. So you’ll be unable to talk about it with the rest. Which is very strange. It destroys the balance in the group.

To come back to the international aspect of your career: you talked earlier about performing in Chicago. Do you mainly perform with European musicians outside of Europe, or do you play with local people on the spot?

At the beginning of my career – let’s say roughly the first 10 years – I always played with Belgian musicians when abroad. But in recent years, it’s mainly foreign bands that ask me to come play abroad. So I’m in two French bands and two Finnish bands at the moment. And we play throughout the world.

What matters when accepting or not accepting a show on the other side of the world?

We travel a lot. Sometimes it’s a bit too much of a good thing. For example, I often play in Mexico. It’s exotic, it’s great to play a festival there, then play two club shows and give an interview. And then you travel to Yucatán in the north to play a concert there. Too often we musicians see this as a bonus. I think we have to assume a certain level of responsibility. Such long-haul flights have an ecological footprint that is actually not okay. So if you do something like that, you should make sure that the tour fits within a long-term vision. What do I mean by that? That you invite the right press, that you ensure that there are other relevant organisers in the room, that your record is in stores when you play somewhere. Actually, it comes down to doing everything that is not just playing around a bit for five days: ensuring that people see you, that you are making contacts, that you expand your network, that you give a workshop in a disadvantaged neighbourhood, for example. Firstly, make sure that it fits within your artistic story, and secondly that you give something back to the local community.

A kind of sustainability, both career-based and ecological.

Voilà. Which also applies to Walter. I want to involve the neighbourhood as much as possible. I not only want to present a high-quality international programme, but also to organise local workshops.

International and hyperlocal at the same time.

Exactly. I learned that from Jef Neve: if you play somewhere, you have to make sure that it’s an investment for the next time. Playing for the sake of playing doesn’t make much sense. I try to take that into account now. For example, if I’m asked to go to Australia, I always try to combine that with interviews, a solo concert, or a session with local people. I always try to make more of it than it is: to use my time optimally. I must add, however, that it’s okay to relax every now and then. It’s alright to visit the pyramids. But it’s important to ensure that you don’t just play anywhere, without it being an investment in the future.

Which is something few musicians think about. Somewhere I understand that: in the first place, you just want to play, to discover the world. It’s to your credit you that you reflect on the impact that has. Perhaps that’s something you learn over time?

Whenever I receive an offer, it’s very tempting to accept it. I find it very difficult to say ‘no’. I’ve been to Japan ten times, Mexico fifteen times, Australia four times. I find the flying and travelling itself fantastic. In any case, I set a very bad example in the area of ecology: I do not sort waste properly, and I drive a car every day, while I could organise myself differently and get about more by train and by bike. There are many things I don’t do well. But I still try to do my part: by eating less meat, for example, and by not flying back and forth to Mexico to play two shows. You simply can no longer justify that: it’s irresponsible. I think that we should all reflect a bit more on this. Because in fact, things are not really going so well.

That’s right. Now then, in addition to your career as an (ecology-conscious) jazz drummer, you also have a life outside of music. How do you combine your hectic existence with the home front?

Spending so much time abroad is usually not easy on your home situation is. Although I have to say that both my ex and my current girlfriend are very tolerant in that respect. Of course it’s never pleasant when someone is far away from home. But I have to say that things are currently in balance. When I’m abroad, it’s usually for a week, after which I’m back home for a week. I used to be away for ten days, then home for one day, and then away for another ten days. That’s difficult, because then you really grow apart as a couple. That’s also one of the reasons why my previous relationship ran aground. It’s just not easy to stay at the same wavelength that way.

Also, I don’t have children, because I’m afraid I’m away so much that … [interrupts himself]. But on the other hand: should there suddenly be children, I will perhaps just organise my life in a different way. I think it’s all possible, as long as you’re together with the right person, who gives you the space to do your own thing. Provided that you also do your best to invest in your relationship from your end at the times you can.

I actually lose money with my label. I invest a lot in it. And in the past even more than now. Only after live performances do sales go well.

In addition to your relationship, there is also your workshop/concert hall Walter. How does this fit into your already busy schedule?

It’s going to be intense. Actually, it already is quite intense. That is partly because I’m going to organise a lot of things that I want to be a part of. That will necessarily mean making choices. For example, I received a very interesting offer to play with a group of really nice, young, musicians from Amsterdam, but that conflicted with one of the concerts I was organising here. And I chose Walter. While I thought: “Jeez, I would’ve liked to have done that.” But I feel I now need be present at Walter, I need to invest myself there, because I’m a bit of a signboard for Walter Which is the way I want it to be. Moreover, I like watching other people play as much as I like to play myself. If I have to refuse an offer because something is planned at Walter, I try to view it as one of my own concerts. It happens quite often. It’s just a part of what I do. You simply can’t do everything. But as a result, I’m strengthening my network so that other things that I find equally important will eventually come my way.

It’s a progressive process, it seems. I have the impression that you are quite flexible and are patiently working on your career?

I’m very organic, in any case. I’ve already had to refuse so many nice offers because something else was already planned. But that doesn’t necessarily mean the opportunity is gone for good. Often such an opportunity presents itself again: so if it’s not for now, it’s for another time. For example, I was asked to play at Gent Jazz with one of the bands I like to play with most, on a day with a fantastic programme. And there was another festival linked to it. But two of my musicians couldn’t make it. And you just have to accept that. You’re looking forward to something for so long, and once the offer comes, you have to refuse it. That was painful: but so be it.

Didn’t you have a tendency to think: I want to do this so much, I’ll just do it with other musicians?

Well, the musicians who were unable to play said the same thing: ‘if you want to do it so bad, do it with other musicians’. But I couldn’t. And I wouldn’t want to either. If you were to pick one musician out of the band and replace him with someone else, the entire group would change. Then I’d rather say ‘no’. That contributes to the long existence of a band. Look at my trio with Mauro: we now play once or twice a year, but it’s been going on like that for ten years already. It continues to be fun, but it doesn’t need to be more. In the beginning, I thought being in a band with Mauro would be my ticket to Pukkelpop. I found it a fantastic band, which I liked to play in. And I thought: we’re going to make it internationally with this band!

But of course that was not the case. Who wants to hear an avant garde band like that at a big festival? Moreover, Mauro was unable to accept most concert offers because he was then playing with dEUS. In the beginning I found that super frustrating. But in the end, I felt like: ‘that’s a sign that it wasn’t meant to be’. That happens when you get older: you learn better to accept things as they are: ‘if not now, then some other time’.

I also have the impression that if you keep pushing for something all the time, you turn people off. Occasionally I push a bit: if it concerns a doubtful situation that otherwise would not happen. But usually I tend to easily let things to. I’m becoming more and more convinced that you can’t actually force anything. If you’re positive and open in life, opportunities will present themselves. If you have an idea of where you want to go – in an open way – a lot will happen along the way that will take you in that direction. But you must also be able to let that go, because in any case your goal will shift over the years. Your ambitions will evolve with you. At this moment I just want to make good music, gain new experiences and play with nice people. If I were to set myself the ambition to become a real star, I would only feel inhibited by the pressure to continually prove myself.

We’ve not dealt with one more aspect of ‘working internationally’. How important are physical and digital releases for you, outside of Belgium? It’s probably different than with a pop & rock act.

That’s a good question. Since I grew up in a graphic environment, an album cover as an object is very important to me. Just like I much prefer to hold a book than an e-reader.

I recently released another new album, a limited edition. And almost 50% of journalists refuse to write a review if they don’t receive a physical copy of the record. But I no longer want to send out vinyls because it costs me too much. Young journalists tend to be more open to a download or streaming link though. But for me, the artwork is inextricably linked to the music.

At the same time, pressing vinyl is actually an ecological disaster. Which is why I’m now thinking about how I can use artwork without having to press vinyl. A USB flash drive with a painting for example: that might be the middle way?

I’ve got nothing against downloading music. But those purely digital releases – streaming one song and then listening to something completely different – are often so volatile. I think it’s fantastic that you can listen to everything at the touch of a button. But it’s a shame that you as a musician get back so little for it. You put so much time and money into it, but the streaming services barely pay anything to the musicians, while they become rich themselves. That’s not okay. On the other hand: if you’re not present on the streaming services, you reach fewer people. I think we’re at a crossroads. I hope that in the near future artists will be paid correctly.

The opaque and often limited compensation by streaming services are a source of frustration for many musicians. On the other hand, you can hardly stay behind: because physical sales continue to fall.

Yet I think that people who really like your music will still buy a physical copy. Especially in my niche. Moreover: by being present online, new people will come in contact with your music, so hopefully in turn you can play more live. So indirectly it translates into income again. It’s a double-edged sword: I’m not against it, I’m not in favour of it. But I think it should be arranged a bit more elegantly.

So you’re present on the streaming services with your own projects?

I am present on the streaming platforms with all my projects. And I believe it does not hurt the sale of CDs. Although CD sales of my label are abominable at the moment. But I think that has more to do with the fact that our niche music is inaccessible to the general public. I don’t lose any sleep over the sales. I don’t worry about those kind of things. I make the record, and if people want to buy it, I’m super happy.

It must be very relaxing not to have to worry about recouping your investment because you have other ways to earn revenue.

I actually lose money with my label. I invest a lot in it. And in the past even more than now. Only after live performances do sales go well: I’ve just sold 60 CDs in one week. Which is great. But as soon as you stop playing, that that number drops considerably. I sell about 25 items per year online. I get my income from playing, playing and more playing. And occasionally by receiving a small subsidie for a specific project.

And how many pieces do you usually press?

250, so I have a big stock at home. I view physical albums as a luxury business card. When I meet interesting organisers or musicians, I give away all my CDs. As far as I’m concerned, they weren’t made to make a lot of money. That’s not going to happen anyway.