The right to fly: Discourse analysis of a sustainability discussion

We live in a small country. A great potential of audiences, artists and organisations beckons beyond our borders. However, working internationally has been a hot topic within the arts sector for quite some time.

On the one hand, to be able to work internationally, you must be given the necessary opportunities and access to the needed resources. On the other hand, the speed and amount of travel can put a strain on your personal well-being and intercultural dialogue. And then there’s the problem of the large ecological footprint …

Climate neutral travel is a challenge that leads to shared uncertainty about how to tackle it. Different views exist, in which facts are intertwined with opinions. The use of language can also add to the confusion or misunderstanding. To structure this complex reality, we will examine a scientific analysis of the discourse on the question: “is frequent flying still OK?”.

Sustainable international collaboration in the arts

Flanders Arts Institute worked for two years on the development process around the arts practice (Re)framing the international [1], which linked the ecological, artistic, human, social and economic meanings of working internationally.

Inspired by A Fair New Idea?!, we tackled the time-out confronting the arts sector in the wake of the corona crisis. An international group of artists and art workers examined these three questions:

- How do we find a balance between working internationally and care for the planet, people and meaningful relationships in the artistic ecosystem?

- How can we tackle the unequal distribution of opportunities and resources for working internationally between and within specific countries and regions?

- How to support international relationships between individuals and collectives wishing to think and act together?

Which conceptual frameworks and arguments can nurture the work of this group? The remainder of this article summarises the controversy around aviation based on the general conclusions of a research report by Ghent University and Université libre de Bruxelles about the sustainability story. The sidebar sketches the context of the study. It closes with a personal response.

Analysis of the controversy: “Is frequent flying still ok?”

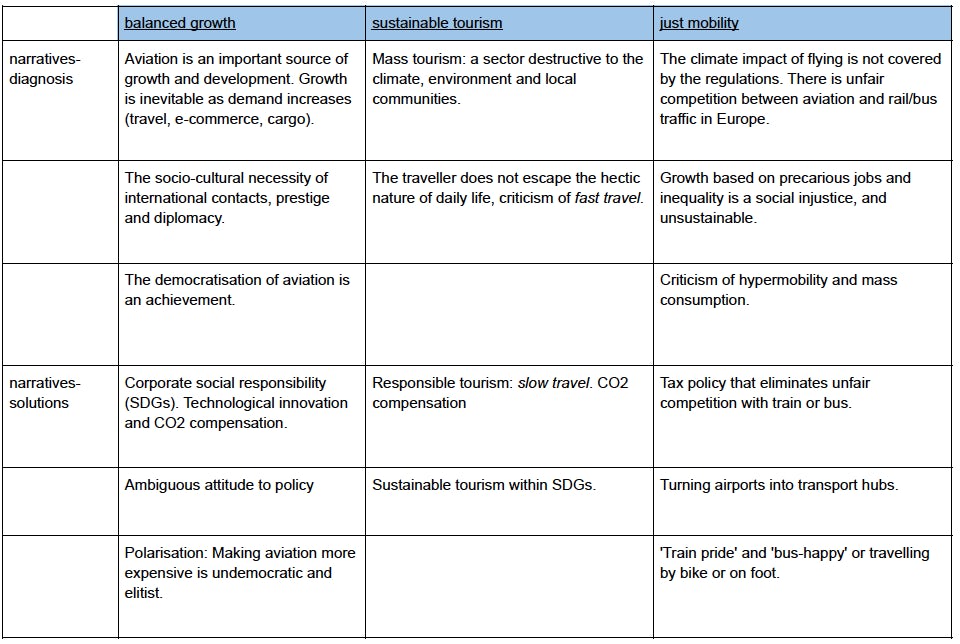

The dataset for this discourse analysis on aviation [4] consisted of 285 public text sources (158 NL and 127 FR) and 5 online interviews. After analysing these sources, the researchers describe three discourses about aviation in Belgium:

- Balanced growth: a growth scenario for the aviation sector is inevitable due to rising demand. Corporate social responsibility and technological innovation offer sustainable solutions to make that growth possible.

- Sustainable tourism: is aware of the negative impact of air travel on the climate, environment and local communities. New travel behaviour can make tourism an engine for sustainable development around the world. This discourse is more present in the Dutch-language sources than in the French-language ones.

- Just mobility: further growth of aviation is unsustainable. A policy promoting a degrowth scenario for aviation and better appreciation of sustainable transport is needed. Travellers can apply the principles of slow travel to discover a new freedom.

The impact of the aviation sector on climate is not denied in any of the three discourses. Summarising, the most important building blocks of these three discourses:

General conclusions

In the end, it turns out that, in general, three discourses appear in the analysis of any controversy, which align with international scientific research:

- A status-quo discourse

- A reformative discourse

- A transformative discourse.

The status-quo discourse recognises sustainability challenges and seeks solutions within existing political, economic and social structures. A reformative discourse starts from a more critical attitude and demands social adjustments in the form of increasingly small changes within the existing system. In the transformative discourse, the aim is to eliminate inequality through radical transformation of the existing system, and social justice is most strongly elaborated.

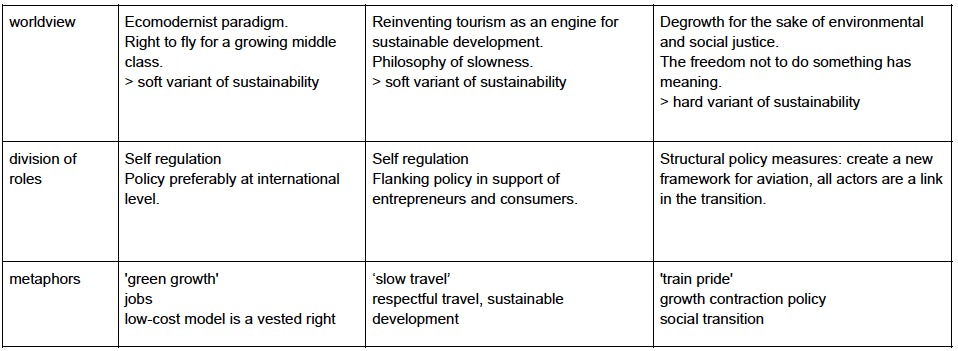

Change always creates friction. In each of the discourses and their narratives, dynamics appear that repeat and perpetuate business as usual. The authors identify four limiting strategies:

- Surrender: TINA, there is no alternative, change is impossible …

- Shifting responsibility: other sectors have an even greater climate impact, unfair international competition, individual action instead of collective action …

- Proposing non-transformative solutions: technological optimism, words without deeds, encouraging voluntary action …

- Highlighting the disadvantages of climate action: importance of jobs, don’t jeopardise acquired freedoms with far-reaching policy measures (see visualisation).

The aim of the report is to stimulate democratic debate and to arrive at inclusive communication. Knowledge of the three discourses increases the insight into one’s own assumptions as well as the possible perspectives of discussion partners.

Narratives or strategies that present observations as immutable or inevitable limit thinking and narrow the discussion. Between opposing narratives in the analyses, points of contact regarding worldview or values do appear. According to the authors, these worldviews offer opportunities.

In both balanced growth (status-quo discourse) and just mobility (transformative discourse), justice emerges in the worldview. This could have a connecting effect as a central value. The authors propose using this material in workshops as a starting point for an open and instructive discussion to avoid deadlocks.

Personal response

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt offers insights that shed a different light on the overall conclusions of this report [5]. According to his research, humans are primarily intuitive beings: instinctive feelings have the upper hand over strategic reasoning. What’s more: arguments are adapted to the intuitions. Connecting with people who hold different opinions is difficult.

“You can use traditional techniques of persuasion when talking to your friends. People will be less inclined to do so publicly, because they’re not prepared to betray their team.”

Jonathan Haidt (social psychologist)

Worth noting: his research showed that people interpret the notion of fairness in two different ways. One sees in fairness a ground for equality, while the other understands proportionality by it. The two views are very different.

Equal rights advocates align with the psychology of freedom and have compassion for victims of oppression. Proportionality supporters related to the psychology of reciprocity and find punishment or retaliation for unfairness legitimate. [6]

These different interpretations of fairness lead to a different understanding of discourses on aviation. Where the report’s authors see a value in justice that the various discourses share, we should heed Jonathan Haidt’s warning.

The right to fly takes on a different meaning in each worldview. The status-quo discourse of balanced growth wants to preserve the democratic character of aviation, because charging for CO2 emissions would make flying elitist.

The notion of social justice is implicit in the reformative discourse on sustainable tourism: the travel industry brings income and therefore development to communities worldwide. In the transformative discourse of just mobility, our individual freedom to fly has been curtailed, for the benefit of people and planet, today and in the future.

In short, these differing views on the right to fly are at the heart of this controversy. Let’s talk about that together.

Footnotes

[1] See also: Do the locomotion, duurzaam internationaal reizen met de trein [Do the locomotion, sustainable international travel by train]

[2] F. De Roeck, Lugen, M. and Block, T. Duurzaamheidscontroverses in België: een discoursanalyse [Sustainability controversies in Belgium: A discourse analysis]. 2021. Brussels. King Baudouin Foundation.

[3] Based on the work of John S. Dryzek.

[4] The other two controversies (meat production/consumption and hydrogen) are not covered in this article.

[5] J. Haidt. Het rechtvaardigheidsgevoel. Waarom we niet allemaal hetzelfde denken over politiek en moraal. [The Righteous Mind. Why good people are divided by politics and religion]. Utrecht. Ten Have. 2021.

[6] This must be distinguished from the political concept of “freedom” as, among others, political historian Annelien De Dijn has described it.

Colophon

authorr: Nikol Wellens

feedback: Tom Ruette, Simon Leenknegt, Dirk De Wit

translation: Dan Frett

thanks to: Ruben Arnaerts, Pulse Transitienetwerk cultuur jeugd media