Photography in Flanders: A multifaceted and full-fledged artistic medium

Photography has been subject to technological developments since its origins, but rarely have these changes been so profound and far-reaching as in the past twenty years. The effects and consequences of the evolution to digital are significant with respect to production, distribution, presentation and consumption. [1]

Photos are ubiquitous today, exist in a wide variety of forms, carriers and applications, and move (sometimes too) freely across the apparently limitless internet.

The impact of the worldwide web on photography manifests itself not only in the more obvious areas. For example, the internet is also at the root of the recent hype surrounding the photo book, which emerged as a kind of tangible counter-reaction. [2] At the same time, the internet and social media resulted in new ways of book distribution.

Photography has always been a medium that was difficult to grasp, but since the 2000s it seems to have transformed into something very slippery. At least when we look at the medium from above and try (in vain) to allocate it a well-defined, permanent place within society, within journalism, within art and culture.

On the ground, however, among the many practitioners of photography in all its functions and dimensions, things are in constant flux. They embrace this multiplicity of forms and applications – they see little need for categorisation except when it comes to support from above – and it becomes an unruly struggle to know as a photographer in which box one best fits.

Within the many initiatives, developments and activities that have taken place over the past twenty years, some tendencies can nevertheless be noted, with the overarching conclusion that photography is increasingly self-willed and determined to take its own, particularly varied path, and that in the process the medium is unafraid of encounters with other sectors, branches of art and industries: quite the contrary. This tendency manifests itself not only in general and worldwide, but also here in Flanders and Brussels.

Historical context

The aim of this text is to map out the photography landscape in Flanders and prepare an up-to-date balance sheet of what appears more than ever to be a broad and dynamic sector. In 1999, just before we entered the new millennium, Erik Eelbode wrote two essays on the state of photography in Flanders that – together with a third field text from 2005 in which he revised the framework and the main lines of the previous two – form the historical context from which this argument emerges. [3]

Central to Eelbode’s overviews is the question from when and to what extent photography was taken seriously as an artistic medium within public art institutions and museums. As a publicist, photo critic and curator, Eelbode primarily referred to the development of well-considered photography collections, but also to the development of a historical and theoretical discourse on the photographic image, including through academic research and education. Finally, he examined which institutions and instruments arose in the wake of this evolution with the explicit desire to draw attention to photography, and how effective they were in doing so.

Based on his great commitment to and ambition for the medium, Eelbode’s conclusion sounds stern: photography here “never entered a wider institutional network”; he calls the interaction between galleries, museums, archives, universities and art schools “particularly poor”; publishers and magazines cannot count on government support; and consequently there is hardly mention of “a broadly informed public and a critical photographic ‘culture’.”

“Slightly hesitant from the 1970s on,” writes Eelbode, “but in the following decades beyond any doubt, photography is recognised and cultivated as a full-fledged artistic means of expression within the contemporary art circuit.” [4] That was at the international level. Flanders, and by extension Belgium, has always lagged behind compared to other countries: here it is mainly the 1980s that count.

For Eelbode, the Provincial Museum of Photography in Antwerp – better known today as FOMU – was a beacon of light in an otherwise fragmented photographic landscape. The establishment of an Antwerp department for the history of photography – which grew out of Gevaert’s publishing department and the merger with the Agfa collection, and located in the then Provincial Museum Sterckshof – was way ahead of its time, even for Europe.

Not that the museum – which set itself the goal of collecting, preserving and studying the objects of the photographic medium (both photos and cameras) – was free of worries at the time. [5] The museum lacked the appropriate resources and people to develop and grow; there was no recognition at national level, and greater involvement on the part of the Flemish Community was lacking, but seemed necessary.

In 2003, the Provincial Museum of Photography in Antwerp became Fotomuseum Antwerp or FOMU. With a young director and a new museum team, the museum pursued a heterogeneous and attractive exhibition policy that featured both young talent and established (international) names. With a view to the future, the museum’s in-house collection and the historical aspect of photography faded more into the background.

Eelbode criticised the fact that no museum for modern art in Flanders had a noteworthy photography collection, despite the fact that these museums regularly present strong monographic or thematic exhibitions. In contrast to the MoMA in New York or the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, for example, they do not treat visual art and photography equally. Eelbode finds the way in which we deal with contemporary photography problematic because of the fragmentary approach and lack of knowledge of photography and its history. The result is an impoverishment, both in the historical discourse and in the medium’s contemporary literature. Fortunately, in the 1970s and 1980s there were still small galleries that kept their finger on the pulse of contemporary photography. [6]

There was only a fragmentary policy on commissioning issued by the government, with the 1994 Documentaire Foto-opdrachten Vlaanderen Provincie Antwerpen as the sole long-term project. The theme was the continuous transformation of open space and the landscape. However, since the territory of these assignments is limited to the Province of Antwerp, which does not always benefit the quality of the work, Eelbode notes that as a Flemish initiative, it “for the time being has not emerged from the shadows, or in any case pales in comparison to the international examples.” [7]

Eelbode’s conclusion, based on his great involvement in and ambition for the medium, is stern: here, photography has “never ended up in a broader institutional network”, the interaction between galleries, museums, archives, universities and art schools he calls “particularly poor”, publishers and magazines cannot count on government support and “there is hardly any question of a broadly informed public and a critical photographic ‘culture'”. [8]

Need for autonomy

But where are we now, fifteen years later? Can we say that photography as an artistic medium is taken seriously enough today? What contributed to this? But also: what recent evolutions have had an impact on the medium, have helped to shape photography or steer it in certain directions? This will be examined and explained in this text.

The conclusion will be that photography today is a full-fledged artistic medium. Thanks in part to the sustained efforts of institutions, large and small venues and initiatives – from above, but certainly also from below – for and around photography, as well as thanks to the extensive attention for the medium from education and research and even in the media. Thus a mood and setting rapidly developed around photography in which the things that Eelbode identified as shortcomings at the time, are now increasingly being addressed. And that in turn has consequences.

Photography today is a full-fledged artistic medium. Thanks in part to the sustained efforts of institutions, large and small venues and initiatives, as well as thanks to the extensive attention for the medium from education and research and even in the media.

Today the many and important roles photography fulfils in society are becoming increasingly clear in the manner in which the medium interacts as well as interferes with different levels and within the different segments. This also entails new responsibilities for the sector, including with regard to visual literacy. What role can the sector play in the necessary effort to make society more aware of the mechanisms inherent in photographic images?

Photography can take the form of a document, of literature, of journalism, of archives, of questions – about the medium itself or about contemporary visual culture. Photography is democratic and accessible. As such, it is also a social medium, which refers to its shared experience as well as to the potential for social engagement and even political activism it carries. It exposes very concrete and factual things, but can also help reveal more abstract issues such as power relations and ideologies. Photography is very directly related to reality, but it seldom expresses it unambiguously.

This enormous stratification and complex richness mean that photography can no longer be reduced to the pure preserve of art or that of journalism/documentary: the dichotomy that photographers all too often find themselves in today when looking for financial and other support. What this text above all aims to demonstrate is the resulting, tangible need for a certain autonomy in the approach to and treatment of photography, within the framework of government support for the sector and in particular for photographers.

The contemporary photobook

The revival of the photobook as an autonomous work, with increased attention from the institutional field as well as among photographers and the audience for photography, contributed strongly to this evolution from 2010 onwards. [9] It shifts the emphasis from the exhibition to the book as a means of displaying and disseminating not only documentary work but also artistic and conceptual work.

Technological changes make photo albums more accessible. They allow especially young photographers to bypass the closed gallery system and get their work out into the world; the publication of books or cheaper zines offers them independence and control. Thus a unique ecosystem of (independent) publishers, book fairs, festivals and prizes soon developed.

Just as the photobook was used as an opportunity to review the history of photography – in general, or per region or country –, the artistic medium itself gradually became the object of research in the arts. In Flanders, Tine Guns (KU Leuven/LUCA School of Arts) wrote a PhD on the border zones between cinema and the photobook, and the Belgian Platform for Photobooks – a website dedicated to the contemporary photobook in Belgium – was founded by Stefan Vanthuyne in the context of artistic research at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp.

In response to the finding that (also in Flanders) the photobook was largely ignored in the history of photography until recently, FOMU in 2019 organised the large-scale exhibition Photobook Belge. [10] In the meantime, the accompanying catalogue was conceived as one of the many books about photobooks and as such became an internationally valued reference work that took its place among similar books from other countries.

Journalism versus art

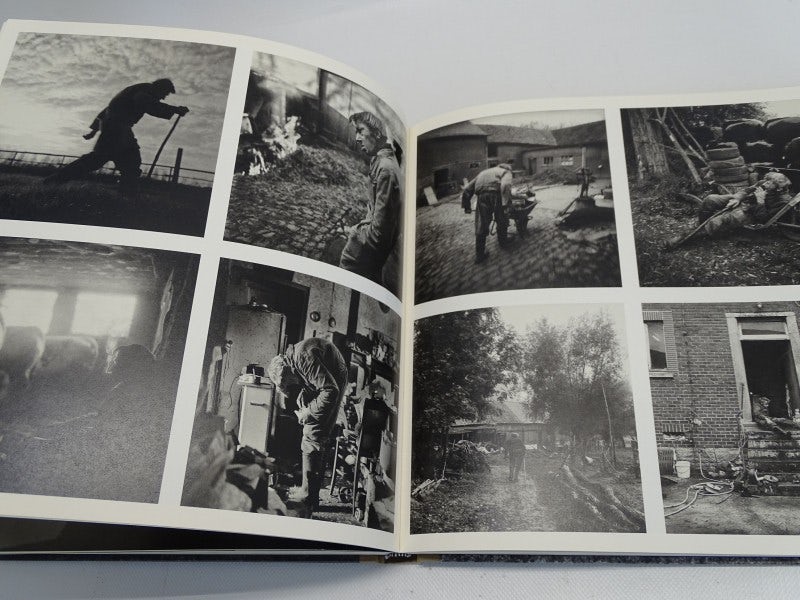

In 2007 it is also a book that, even more than the exhibition of the same name at Fotomuseum Antwerp, gave photography in Flanders a significant boost among the general public: Belgicum by Stephan Vanfleteren, a photographer who works for the press and at that moment managed to distinguish himself from the pack with his own style and signature: slow black-and-white photography. The book was published by Lannoo. Never before has such a wide audience been reached (unless it would be the immediately subsequent exhibition and book Portret) and were so many copies of a Belgian photobook sold. [11]

In this respect, the fact that Vanfleteren was a press photographer who gradually evolved into an art photographer during his extensive career is not unimportant. Flanders has a rich tradition in photojournalism, with a certain peak in the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Leaving aside Dirk Braeckman for a moment, in the early 2000s it was mainly documentary and press photographers who enjoyed some level of name recognition in Flanders, [12] partly cultivated by the media in which they published, exhibitions in museums and cultural centres, as well as books – often also published by Lannoo – that followed in the footsteps of the success story of Belgicum. [13]

Parallel to this shift in which photojournalism is now also appearing in galleries, museums and photobooks, media support for photo reports begins to wane. The market for photojournalism in Flanders is (too) small; [14] for a long time – for economic reasons – the printed press was not sufficiently active in news photography.

In addition, committed photojournalism lost moral authority in an era of compassion fatigue, instant gratification and an oversaturated visual culture. Images of the moment of an event itself, which can be shared immediately thanks to far-reaching digitisation and social media, became more important in the news culture: the importance of the feeling of ‘being there’ exceeded the better image quality or the possibility of reflection on a photo taken after the event.

As a reaction to this digitisation, we see a flourishing of self-reflective experimental artistic practices that often hark back to the (analogue) photographic process and the material characteristics of the medium itself. This had already been visible for a time in the work of artists such as Dirk Braeckman, Marc De Blieck and Aglaia Konrad, but more recently was also the driving force behind makers such as Sine Van Menxel, Tom Callemin, Bruno V. Roels, Dominique Somers and Dries Segers.

In documentary photography we again see a more detached style emerging, [15] but also a more conceptual approach, in which the genre itself is often called into question: think for example of the work of Max Pinckers, Geert Goiris, Jan Kempenaers and Jim Campers.

In addition, we also see a new focus on (for lack of a better word) ‘essayistic’ photography: work in which photographers create longer projects and stories, often combined with an editorial and journalistic practice. In this regard, names such as Sanne De Wilde, Ans Brys, Titus Simoens, Jan Rosseel, Thomas Nolf, Rebecca Fertinel, Frederik Buyckx, Heleen Peeters and Bieke Depoorter come to mind.

Research and education, theory and criticism

Research in the arts has taken off since 2006, and photography too is occupying an increasingly prominent place. Today, all Flemish art colleges have one or more research groups within which projects closely related to photography can be pursued. On the basis of lectures, symposia, publications and exhibitions, whether or not in collaboration with institutions and museums, these research groups continue to construct a relevant and up-to-date theoretical discourse on photography.

A recent example of this is the exhibition The Photographic I – Other Pictures from 2017, for which the S.M.A.K. and the Thinking Tools research group (with Bert Danckaert, Inge Henneman, Geert Goiris, Charlotte Lybeer and Steven Humblet [16]) of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp joined forces.

This research in photography often has to do with the self-reflective, artistic practices of photographers and visual artists who consciously work from a philosophical-conceptual angle around the photographic image, the photographic process and the specific characteristics of the camera itself.

The documentary genre, the way in which photography relates to the world, and the photo as a document also become the subject of artistic research, including in the work of Mashid Mohadjerin, Max Pinckers and Michiel De Cleene: the latter two co-founded the School of Speculative Documentary at the Ghent Royal Academy of Fine Arts (KASK).

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

The Photography Expanded research group at the LUCA School of Arts in Brussels reveals that artistic research into photography often touches on so much more than just the photographic aspect, where among others Hana Miletić, Els Opsomer and Maarten Vanvolsem are working on or have completed doctoral projects.

An important aspect of arts research is the transition to education, and photography is no different. Researchers are often linked as (guest) lecturers to the institution in which they conduct their research, and research projects are regularly discussed in regular educational activities, either via project weeks or master classes and workshops.

Thanks to the many and different photography courses in Flanders, photography students can now embark on a broad or very focused study, depending on the institution where they are enrolled, while also developing their own unique emphasis. The teaching staff consists largely of artists and photographers with solid practice and work experience; they are makers or theorists who enjoy the necessary prestige in the field of art or work, both at home and abroad. Alumni are often still involved in the programme, for example as a jury member.

LUCA School of Arts offers photography at various campuses throughout Flanders at different levels ranging from a specialisation within a bachelor’s or master’s degree in Visual Arts to a professional bachelor’s in Audiovisual Techniques, from professional and applied to academic and artistic. The Royal Academies of Fine Arts are located in Ghent and Antwerp: both offer a master’s degree in Visual Arts with a specialisation in Photography.

Like Narafi (LUCA School of Arts Campus Brussels), photography at Sint Lucas Antwerp (Karel de Grote University of Applied Sciences and Arts) is a study specialisation under the professional bachelor’s programme in Audiovisual Techniques, the only course for which no artistic entrance test is required. In Antwerp, students are primarily prepared for a profession in the creative or journalistic sector, but the perspective is also broader. There is the option of following a subsequent, separate master’s degree; this is seen as the first stage in developing a career.

Moreover, virtually all study programmes have a strong link with foreign countries through exchange programmes and international collaborations, visits and participation in cross-border exhibitions and projects, or through the influx of foreign students.

Due in part to the steadfast investment in academic research and education, theoretical discourse on photography in Flanders has continued to develop in a thorough and sustainable manner, with an eye for the history of photography as well as the current issues the medium is confronted with. The Lieven Gevaert Research Centre for Photography, Art and Visual Culture also plays an important role in this.

Founded by Jan Baetens and Hilde Van Gelder in 2004, today it is a collaboration between KU Leuven and its French-speaking counterpart UCLouvain, with which the LUCA School of Arts is also affiliated. In addition to the theoretical books published in the Lieven Gevaert Series, they also run the bilingual, peer-reviewed e-journal Image [&] Narrative.

Critics and publicists such as Eelbode himself, but also Dirk Lauwaert, Inge Henneman, Bert Danckaert and Steven Humblet – who often also have a link with education and research – contribute in magazines such as HART and De Witte Raaf.

FOMU (partly under the impulse of Eelbode and Henneman) also contributed to critical reflection on photography through its magazine. Today the museum continues to do the same, for some time also via Trigger magazine, an online platform and paper magazine that encourages in-depth debate on photography, especially from a social point of view, and which also has a strong international orientation via its English-language texts.

In the regular media, photo criticism is no longer done as it was before by someone like Johan De Vos, for example. Photography exhibitions or photobooks that are not liked by the editors are simply not covered; [17] the reviewer’s role is rather that of a guide who brings interesting work to the attention of the public.

Most critics who regularly write on photography – such as Jozefien Van Beek, Jan Desloover (De Standaard), Rik Van Puymbroeck, Tom Peeters (De Tijd), Sophie Crabbe (HART) – also write about art in general, about literature or other subjects. On the other hand, Stefan Vanthuyne – albeit as a freelancer – writes exclusively about photography, including for De Standaard.

Museums and galleries: Where to view photography?

The period around 2010 again brought major changes for FOMU. The museum gained its national recognition in 2009 after director Christophe Ruys resigned a year earlier and major renovations had taken place in 2006. Elviera Velghe became director in 2010. Curator Inge Henneman, who is also editor-in-chief of the magazine, went freelance after ten years. She was relieved by Rein Deslé as curator and Tamara Berghmans as curator-conservator; two years later, Joachim Naudts would also join the curatorial team.

In 2015, FOMU was given the archives of Agfa-Gevaert and photographer Herman Selleslags for safekeeping. A year later, the museum unveiled the Lieven Gevaert Tower: an extra six hundred square metres plus a climate-friendly warehouse.

Despite minor concerns and criticism here and there, [18] this young team would provide the museum with a solid place on the European contemporary photography stage, thanks to topical temporary monographic and thematic exhibitions, and collaborations with external curators and institutions.

There are three other galleries in Antwerp that deal almost exclusively with photography. [19] Gallery Fifty One mainly treats the more classical art photography, but also has contemporary names in house. IBASHO specialises in Japanese photography, and Stieglitz19 mainly presents up-and-coming Asian talent. [20]

While the M HKA presented another two exhibitions in 2000 in which the photographic image was central, [21] it would only do so four times in the following twenty years. [22]

Photography is also treated sporadically in the other museums for contemporary art. The S.M.A.K. in Ghent only saw the photographic light around 2014; since then, the counter is at three monographic and a two-part thematic group exhibition. [23] We see a similar trend at WIELS in Brussels, with four monographic exhibitions since 2012. [24]

The most striking institution in this contemporary arts field, however, is Museum M in Leuven. With the exception of Roe Ethridge in 2012 and Thomas Demand in 2020, the museum has presented exclusively Flemish names in a solo arrangement: Katrien Vermeire in 2010, Dirk Braeckman in 2011 and 2018 (on the occasion of the Venice Biennale, curated by Eva Wittocx), Geert Goiris in 2013, Aglaia Konrad in 2016 and Jim Campers in 2018.

The many cultural centres in Flanders also regularly organise topical exhibitions with and about photography. To list them all would take us too far astray, but Photo Friction, the successful group exhibition from 2018 in De Garage in Mechelen serves as a good example. Tique Art Space in Antwerp and NO/ Gallery in Ghent are two spaces that offer exhibition opportunities to young photographers and artists – NO/ Gallery is also an artist-run space. Finally, there are a large number of galleries in Flanders that deal in contemporary art, and as such are also home to one or more artists who work with photography in different ways.

Quirky and diverse Brussels

In the 1990s, the Brussels Centre for Fine Arts regularly hosted fine monographic or retrospective exhibitions. Although the house no longer has a permanent photography curator since the name change and change in policy, it has continued to work hard on a varied and cross-border photography programme.

Photography plays an important role in the partnership with the Europalia festival, but also with the Afropolitan platform, which presents work related to Africa and its diaspora. BOZAR is also home base for the biennial Summer of Photography, which since 2008 has presented a variety of visions on a particular theme, the first two editions of which focused on a specific region. The most recent edition – that of 2018 – was broader than ever. It covered photography and related media, was a collaboration between sixteen partners, and was shown at eleven exhibition venues in Brussels.

While Box Galerie exclusively presents (rather classical) photography, larger contemporary art galleries such as Greta Meert, Xavier Hufkens and Rodolphe Janssen mainly represent established international artists working with photography, or photographers embraced by the art world. Cultural Centre Botanique has been presenting photography sporadically since the 1990s (with a small predilection for Magnum and street photography) and the Gallery is also a venue for young and – mainly but not exclusively – French-speaking Belgian makers.

Contretype too has been in existence since 1978, and remains the only venue open to residencies for national and international photographers. Since 1997, the start of the residency programme, artists in residence at the Brussels centre for contemporary photography have included Bernard Plossu, Elina Brotherus and JH Engström.

Fondation A Stichting, located in a former shoe factory in Vorst, is an initiative of collector Astrid Ullens de Schooten, in collaboration with curator Jean-Paul Deridder, who felt that in addition to Antwerp and Charleroi, Brussels also needed its own venue dedicated to photography. The foundation opened its doors in 2012 with an elegant double exhibition by Judith Joy Ross.

Although specialising in American photography, the foundation alternates easily between (mainly) contemporary European and Japanese photography. Young Belgians are also given opportunities. Fondation A Stichting presents three exhibitions a year: the focus is on documentary work. The bizarre year 2020 was seized by Mrs. Ullens de Schooten to reinvent the foundation, however, without Deridder.

The most alternative, even downright rebellious, Brussels player to promote photography over the past five years is the Recyclart arts centre, which was launched in 2000 with the support of both the French and Flemish Communities. Under the impulse of Vincen Beeckman, himself a photographer, photography was used as a social link between the centre and the neighbourhood (at that time the Marolles: Recyclart was later forced to move).

Projects with disposable cameras are set up in collaboration with children and the homeless. Also unique is Le Fusée de la Motographie de Bruxelles, a nomadic project with photos in wooden boxes, and the long-running, informal series artist talks with young photographers from Belgium and abroad, which has been taking place on an occasional basis since 2013 under the name Extra Fort.

Photo festivals and public events

There have been a number of photo festivals in Flanders in the past decade. The 80 Days of Summer photo festival took place in Ghent twice, organized by Historische Huizen Gent, and coordinated and curated by Anke D’Haene. However, the photography had to compete with the context of the festival, namely the special heritage locations where the exhibitions took place.

Photo festivals organised by the city frequently turn into a vehicle for city marketing, and photography – however high the quality may be – is often secondary. [25] It’s a delicate balance, but the impact on audience reach and the perception of the festival should not be underestimated.

When the festival is led by a strong cultural player and is surrounded by the right partners and sponsors, as in Liège with the Biennale de l’Image Possible (BIP) [26], the image usually remains firmly in the foreground. In 2021, the city of Kortrijk will be organising the Track & Trace photo festival, with again Anke D’Haene as coordinator, and Lize Rubens, Dieter Van Caneghem and Lieven Lefere as curators. Here the emphasis was fully on photography, with the (beautiful) exhibition spaces of secondary importance. It’s an approach that pays off in terms of attention from the press and public. Of course, a solid programme, in which both international names and local photo clubs are on display, also helps.

Knokke-Heist has been strongly committed to photography for more than twenty years, first in the form of an international photo festival at various locations at the seaside resort, in recent years also increasingly managed by Cultural Centre Scharpoord. For the photo festival, Christophe De Jaeger (long associated with BOZAR in Brussels as a photography programmer, now involved in the experimental BOZAR LAB) took on the role of curator. Since 2014, Unknown Masterpieces has also been part of the festival, an exhibition with work by young and unknown local talent. In the recent past, photo clubs were also given space. Traditionally, the World Press Photo has its Belgian premiere here.

In Brasschaat, it is also the Cultural Centre, together with Lutgard Heyvaerts and Jeroen Janssens, that is the driving force behind the regional and biennial Photo Forum Brasschaat, which since 2016 has been showcasing well-known and lesser-known talent.

AntwerpPhoto Festival is an international biennial for photography that is not organised by the city but by Kaat Celis, director of the non-profit AntwerpPhoto. During the first edition in 2018, the festival had Anton Corbijn as a major crowd puller, but attention was also paid to international photojournalism (via the Prix Carmignac du photojournalisme) and the festival showed a sample of what Belgium has to offer in the field of photography (Iconobelge I). [27]

Celis is also the driving force behind De Donkere Kamer [The Darkroom], an evening-filled programme about photography before a live audience that was imported from the Netherlands. Since 2016, the event has been held six times a year, each time at a different cultural centre in a different Flemish province. The programme aims at an attractive mix of well-known names, topical themes and young talent from a pool of Flemish, Dutch and international photographers.

Support and visibility of (young) talent

The varied and well-organised photography courses at the Flemish and Brussels art colleges offer young, ambitious photographers a solid development context and a nice springboard, but once they have jumped, one can only hope for a good landing and further growth and development in the artistic field. Especially for the photographer who sees himself in the first place as an autonomous creator or author, it is no easy task to develop further and to connect with the international field. Working hard, holding a second job in addition to photography, and looking for opportunities, (international) contacts and financing is the most common way to get ahead.

In Leuven, the UNEXPOSED platform has been organising PhotoTWENS since 2013, a modest competition that rewards a new generation of photographers each year with a local exhibition. Between 2013 and 2016, BOZAR supported the Belgian photography scene through the BOZAR Nikon Monography Series Award, which again honoured with an exhibition a long-term or in-depth project by a photographer resident in Belgium.

Contests with cash prizes that enable the photographer to start or complete a long-term project are virtually non-existent here. In 2018, as part of the AntwerpPhoto Festival, the Limaphoto Prize was awarded, a private initiative with a sum of 7500 euros attached. And in the context of Track & Trace in Kortrijk, this year a sum of 5000 euros was awarded to the winner of the Grand Prix Roots Advocaten for documentary photography. Both prizes were awarded under the impulse of Jozef Lievens.

Corporate sponsorship is a delicate theme in the world of art and photography; on the other hand, it does represent financial opportunities for makers. De Donkere Kamer also provides modest but important financial support to the young photographers who come to pitch their projects live: part of the entrance fee is distributed to the pitchers by public vote.

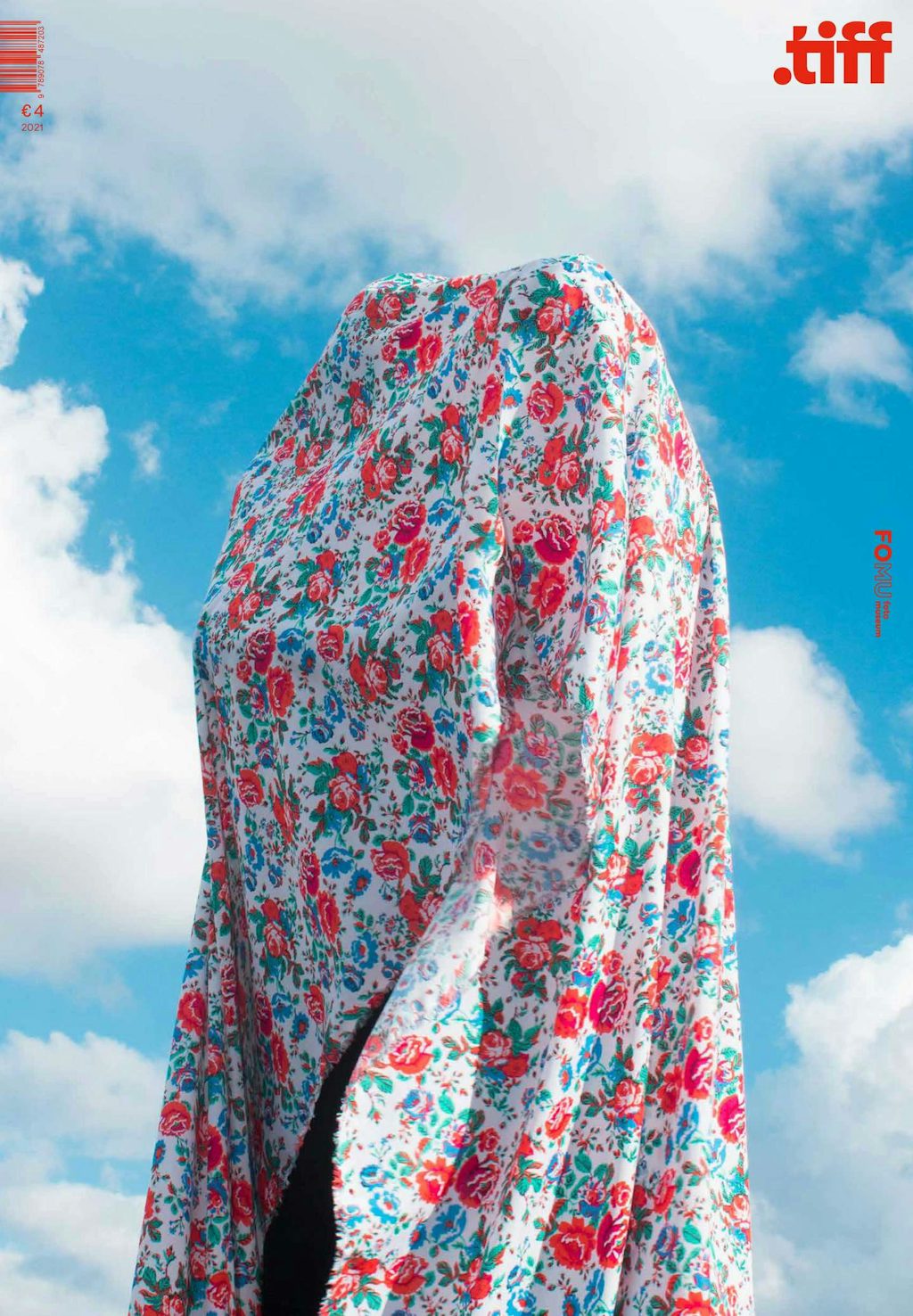

Since 2012, FOMU has been actively targeting young Belgian talent via .tiff, an annual magazine and exhibition featuring ten emerging photographers, selected from a pool of sector-nominated talent. Since 2017, this programme has been part of Futures, a European platform for new talent, which focuses on professional and artistic development through events and online activities. As part of the .tiff programme, those selected are also given the opportunity to meet experts and professionals from the Flemish and Dutch sector.

The Flemish Academies encourage their students to apply for the International Talent Program of the biennial BredaPhoto in the Netherlands. When it comes to specific networking events (outside the context of a festival), Plat(t)form of the Swiss Fotomuseum Winterthur continues to stand out as international meeting place. Each year, experts nominate promising photographers (among them Belgians) to present their work to the public and professionals.

In recent years there have also been solid initiatives by Kunstenpunt / Flanders Arts Institute to make Flemish and even Belgian photography known abroad. On the one hand, since 2019 there has been an annual call to organise an event through a Flemish-Walloon collaboration during the well-attended, annual high mass Les Rencontres d’Arles. On the other hand, there is Turning Photography [28], the internationally oriented website about Belgian photography that was created following the Belgian participation of Dirk Braeckman in the 2017 Venice Biennale.

It is striking today that the gap between the amateur circuit and the professionals (makers as well as experts) has become much smaller thanks to organisations such as mentormentor and BREEDBEELD, resulting in a smooth exchange of knowledge and experience.

Mentormentor was founded in 2015 by Anja Hellebaut and Lisa Van Damme, with the aim of providing professional support to photographers in the form of personal guidance. Through reviews, extended projects, workshops and master classes with reputed contemporary photographers, they offer non-professional photographers the opportunity to continue to develop, after or without prior training. In the past Mentormentor has worked with names such as Max Pinckers, Geert Goiris, Laura El-Tantawy and Bieke Depoorter, and organised collaborations with among others FOMU in Antwerp and S.M.A.K. in Ghent.

BREEDBEELD is the new name of the Centrum voor Beeldexpressie [Centre for Image Expression], resulting from the transformation of the membership organisation into an accessible source of support for the amateur image maker. The young team has succeeded in responding cleverly to the fact that with an up-to-date and unifying range of projects and services, contemporary amateur photography has long outgrown the dusty premises of the classic photo clubs.

Chances and opportunities

Eelbode correctly stated in 2005 that while photography has many facets, it itself is elusive. This is even truer now than then: at that time the digital revolution had only just started and Facebook was only one year old. However, if these different forms of photography – Eelbode calls them fashion, science, document, reportage, studio, publicity, art and family album – each had their own agendas and mutual agreements and their specific technical conventions, then today those categories, partly thanks to far-reaching digitisation, are challenged and mixed together, in the first place by the makers themselves. Art photographers make editorial contributions, fashion photographers make political statements through their work and documentary photographers venture into fiction.

This ‘new’ freedom and fluidity of movement means that more than ever photography is in a constant state of change. Today photography thrives equally well outside the walls of a gallery or museum, and the medium adapts easily to different situations and environments.

In Flanders, too, photography has become noticeably more heterogeneous, more experimental and more versatile, albeit at a slightly slower pace and more laboriously than abroad. This versatility was celebrated in 2017 at FOMU under the title Braakland, a seven-month ‘open festival’, during which the museum transformed its top floor into an experimental space for long and short-term projects. In addition to exhibitions, artist talks, debates, one-night events, portfolio-viewings, screenings and many collaborations, there was also a call for a museum take-over.

More than ever photography is in a constant state of change. Today photography thrives equally well outside the walls of a gallery or museum, and the medium adapts easily to different situations and environments.

For those attempting to survey the Flemish photography field from the outside, it often looks fragmented: initiatives are frequently small, independent and scattered. Yet there is a lot of connection and cooperation, quantitatively as well as qualitatively.

However, within this broad and varied sector, there remain many shared needs that no one understands better than the sector itself. Which is why it is important that there is some form of association. A consultation platform has already been started at Flanders Arts Institute with artists and photographers, curators and critics as well as teachers and researchers, to exchange knowledge and expertise within the sector and to learn what they can do together to support photography in Flanders.

However, more versatile does not mean more diverse. The remarkable finding is that photographers of colour find it very difficult to find their way into the photography field. Here lies one of the biggest challenges for the coming years: how can this attractive and democratic medium be opened up so that the sector becomes more inclusive and accessible? The share of female photographers is gradually increasing, but that too could be much better. At present, contemporary art is more diverse than photography. There is a need for deep introspection at institutions and in education, as well as a need for solutions.

Photography clearly touches on a lot; both the individuality and the idiosyncrasy of the medium are contained in this observation. Rather than seeing this as a weakness, we should see it as a strength. Instead of discussing the place of photography, the question of where exactly the medium belongs and who or what can be attributed to it, instead of considering photography as a subordinate medium and subjecting it to the dynamics of other sectors, it would be better to start from the medium itself.

Which means: granting photography freedom and independence, and from there working in a binding way with the other sectors and media it comes into contact with or in which it plays a role; highlighting its different genres and applications; seeing where and how exactly it can create meaning and add something to our culture, to our society.

In order to achieve this, to give photographers even more opportunities to grow their practice and continue to develop, there are certainly still opportunities for the Flemish government. It would be a good idea, for example, to have more photography experts sitting on the assessment committees of the Arts Decree (there are very few at the moment), as well as to involve them in the purchasing policy of the Flemish government and other public bodies. Another recommendation is to include residencies specifically for photography in the support provided by the Arts Decree. In addition, there is a need for a well-considered policy on commissioning photographers, so that the tasks commissioned not only support them, but also add value to society.

The difference with other countries is particularly great when it comes to visibility – not least in terms of visibility abroad. Online platforms and social media, accessible at all times and worldwide, are underused in the promotion of Belgian photography. Within the policy of the Flemish government, one could look for a venue for photography abroad – Flemish cultural centre de Brakke Grond in Amsterdam can serve as inspiration here.

Inspiration for all of this can be drawn from Flanders Literature, which supports the literature sector in Flanders. There are indeed relevant similarities. On the one hand, because the written word lives and moves in various forms and applications in art, culture and society, and on the other hand, because a significant number of photographers can increasingly be regarded as autonomous author. Following on the new Flemish literature prizes recently created by the government, a Flemish photography prize would therefore not be out of place.

While looking ahead, however, the rich past must not be lost sight of. More attention should therefore be paid to important archives and photo collections. There is a need for government instruments to open these up – think of the fantastic photo archives gathering dust in heritage institutions. In this way, a lasting interaction can arise with the institutes, which through their collections and programmes engagingly put the past in a dynamic relationship with contemporary photography.

Footnotes

- Pijarski, Krzysztof. On Photography’s Liquidity, or, (New) Spaces for (New) Publics? Why exhibit? Positions on Exhibiting Photographies, ed. Sikking, Iris & Rasterberger, Anna-Kaisa, Fw:Books, 2018.

- In this respect, parallels can also be drawn with the music sector, see the mp3 and the revival of vinyl records.

- Eelbode, Erik. ‘Groeten uit pakhuis ‘Vlaanderen’’. Boekman 63, 2005.

- Eelbode, Erik. ‘Van pakhuis Vlaanderen tot Beeldnatie.’ De Witte Raaf, 1999.

- Ibid.

- Eelbode mentions among others Paule Pia in Antwerp, ‘t Pepertje in Diepenbeek, XYZ in Ghent and DB-S in Antwerp – ‘t Pepertje was an initiative of Johnny Steegmans and Johan Swinnen, XYZ of Dirk Braeckman and Carl De Keyzer.

- Eelbode, Erik. ‘Groeten uit pakhuis ‘Vlaanderen’’. Boekman 63, 2005.

- Eelbode, Erik. ‘Van pakhuis Vlaanderen tot Beeldnatie.’ De Witte Raaf, 1999.

- It is striking how much the photo book is absent from Erik Eelbode’s texts, an important indication of how great the impact of this new attention to it was: before that, it was of little or no importance.

- See fomu.be

- At the end of 2018, the counter stood at 14,000 copies. This includes both the edition at Lannoo and later the one at Hannibal.

- Think of Michiel Hendryckx, Jimmy Kets, Filip Claus, Bruno Stevens, Nick Hannes, Gert Jochems and of course Carl De Keyzer.

- At the same time, spurred on by Vanfleteren, the publisher Kannibaal/Hannibal was founded (today Hannibal Books), which positioned itself in the same market as Lannoo, but with an eye on foreign countries. Gautier Platteau, the publisher with whom Vanfleteren had achieved his success at Lannoo, would also join Kannibaal/Hannibal some time later.

- Due to the grouping of media houses and newspapers that are increasingly cooperating across borders, there is a lot of exchange with the Netherlands, where Flemish press photographers also work regularly.

- In this respect, the influence of American photographer Alec Soth on the young generation should not be underestimated.

- Bert Danckaert, Charlotte Lybeer and Geert Goiris all obtained doctorates in the arts at the Antwerp Academy.

- In any case, it is not easy to get non-mainstream artistic photography noticed by editors, due to a lack of space, but ultimately also of targeted expertise in that area.

- De Vos, Johan. Het FotoMuseum: een pleidooi voor meer licht’. Rekto-Verso, 2012.

- In Bruges, 44 Gallery existed until 2020 as a gallery that only showed photography. In 2021, Fragma Gallery was founded in Kortrijk, in the wake of the photography festival there.

- Harry Gruyaert, Bruno V. Roels, Stephan Vanfleteren and Jacques Sonck are the Flemish names with whom Fifty One collaborates. Ibasho also showed work by Sarah Van Marcke and Max Pinckers. Stieglitz 19 also has Thomas Vandenberghe, Vincent Delbrouck and Sybren Vanoverberghe under its roof.

- Exhibitions of Wim Cuyvers & Marc De Blieck and of Maarten Vanden Abeele.

- Craigie Horsfield and Allan Sekula in 2010, David Claerbout & John Gerrard in 2014. In 2021, Mashid Mohadjerin had a modest, but nevertheless full-fledged solo exhibition there.

- Thomas Ruff was there in 2014. Larry Sultan followed a year later (MSK’s opposite neighbour Julia Margaret Cameron) and in 2017 there was James Welling. Group exhibitions The Photographic I and II took place in 2017 and 2018. Note: the SMAK website does not currently contain an archive to search.

- Leigh Ledare in 2012, Robert Heinecken in 2014, Sammy Bajoli & Filip De Boeck in 2016 and Wolfgang Tillmans in 2020.

- At this writing, Tourism Ostend is working on an ‘International Photo Festival’, but little else is known about it.

- Since 2016, BIP also has a photo book festival as a satellite: Liège Photobook Festival.

- AntwerpPhoto could not go full steam ahead in 2020 because of the coronavirus. The festival limited itself to an Iconobelge II, this time in the Handelsbeurs, with a focus on Belgian fashion photography.

- This platform presented a wide selection of Belgian photographers and artists working with the medium of photography, and also included essays and interviews