To consider and to commemorate. From ancient tradition to a lively look at the future

The importance that Flanders attaches to music is as old as the region itself. In historical retrospect, it is remarkable how, over the years, knowing and practicing music has gained as prominent a place in Flemish society as listening to it. Since time immemorial, music has not only been used, created and savoured; it has also been developed, considered and studied.

How this came about is a far-reaching question. It may well be related to geographical conditions. Flanders is flat and centrally located, with a fairly mild climate. So it is no coincidence that it has seen its share of conflict. People live close together, enjoy the good life and have to suffer rather drizzly weather now and then: excellent reasons for a thriving social life.

The region’s historic function as a crossroads brought in a wide range of different influences and a sort of genetic wanderlust.

Having to deal with several languages and significant traffic encouraged inventiveness and an unmistakable feeling for what state-of-the-art might mean, either literally or figuratively. The crossroads function facilitated an early humanistic disposition, a tendency toward intellectual curiosity and contemplation.

It is not too far fetched to assume that this historical-geological-sociological cocktail lay at the basis of the evolution and status of classical music in Flanders. The long tradition of gathering together, eating, drinking, and communicating, seriously or otherwise, and ‒ thus ‒ making music continues to leave its traces in what is, however you look at it, a remarkable preoccupation with music that still exists in Flanders today.

Bart De Baere, the curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) and a progressive voice where we might not expect to find one, once said the following about the visual arts in Flanders:

“In our country, we make art the way other countries make wine. It is something we have done for centuries. […] The story began in the late Middle Ages, when well-organised workshops exported illuminated manuscripts, altar pieces and tapestries from our cities to all corners of Europe. Artists such as Van Eyck and later Rubens and Van Dyck worked for the most powerful courts of their time. Much of this history remains preserved in our churches, castles and museums. Young people growing up in historic cities such as Bruges, Ghent, Antwerp, Mechelen, Leuven or Brussels see testimonies to a rich artistic tradition everywhere. That can put ideas into the heads of young people who are sensitive to them.“

These words apply perfectly to music in Flanders as well. It was specifically in the late Middle Ages that the Flemish polyphonists (from Dufay to Josquin and Obrecht to Willaert and Ockeghem) trained as vocalists and composers at our cathedral schools. They went to work at the powerful courts of Italy, in particular, thus establishing the formal framework within which southern talent and inspiration was able to develop in subsequent generations.

Later, from the Baroque to the classical and Romantic periods and even until the Second World War, Flanders was known more for its performing musicians than its composers – or, one might say, more for its craftsmanship than its inspiration.

From the 1950s onward, Flanders once again experienced highly regarded compositional activity, albeit, as would thereafter prove the fate of the avant-garde everywhere, with limited resonance and with more attention to art itself than to its users and witnesses. The music was seldom flamboyant, with its almost scientific, progressive ethic. It was with good reason that popular music emerged during that time ‒ a laudable genre that generated great publicity and willingness to listen, but is not the topic of this text.

In any case, it does not seem illogical that Flemish musicians, ensembles and composers have earned high esteem in the most diverse disciplines of the realm of classical music. Nor does it seem coincidental that this applies all the more to the extremes of the musical realm: ‘early’ music and ‘new’ music, the very domains in which careful study and structured thinking are the order of the day.

Early music

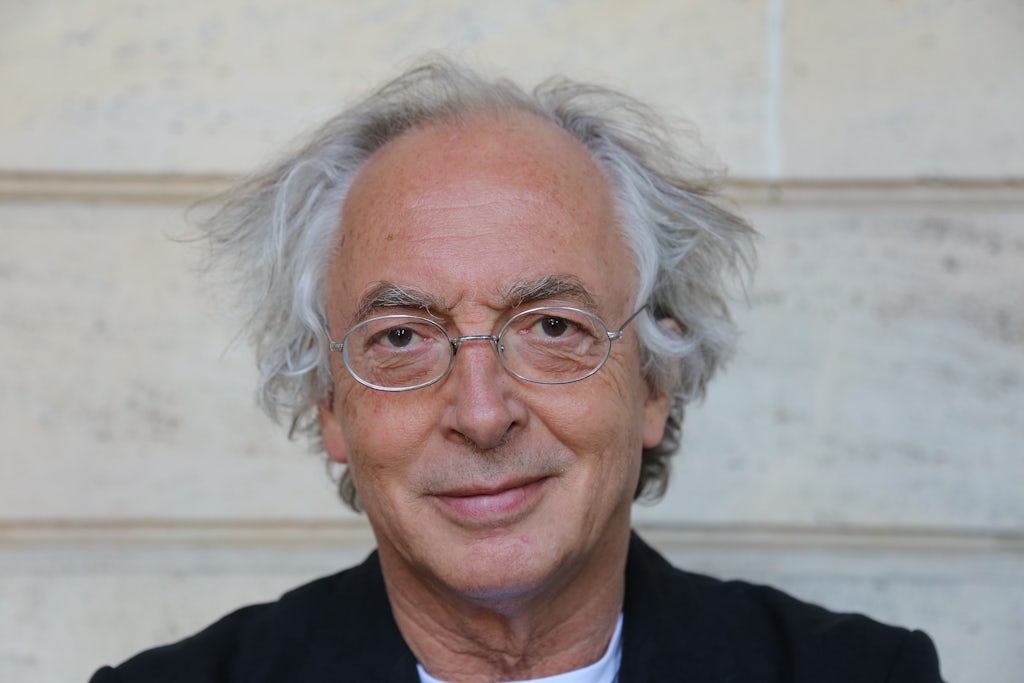

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the movement known as ‘early music’ arose, promoting authentic performance practice ‒ today referred to somewhat more modestly as Historically Informed Practice (HIP). It is no exaggeration to state that Flanders produced significant pioneers in this field who have continued their work to this day. A clear example is the role of the conductor Philippe Herreweghe. In 1970, he founded the Ghent choir Collegium Vocale, thus helping determine the sound of Bach in the 20th and 21st centuries. In recent decades, Herreweghe has also focused his research efforts on more modern repertoire and instruments: as well as being a guest conductor with international orchestras, he is also the honorary conductor of Antwerp Symphony Orchestra). Even earlier pioneers were the Kuijken brothers (violinist Sigiswald, viol player Wieland and flautist Barthold), who are still courageously leading their ensemble La Petite Bande, originally established at the request of Gustav Leonhardt.

René Jacobs, who began his career as countertenor and is now one of the most lauded conductors of opera and other vocal work, comes from the same artistic lineage. Oboist Marcel Ponseele and flautist Jan De Winne, also worked in various groups before establishing their ensemble Il Gardellino in the mid-1980s. Over the last fifteen years, it has been B’Rock Orchestra in particular that has ushered in a new generation: besides being a top quality period orchestra, it is also regularly involved in productions focusing on new music. Its founding member Frank Agsteribbe is no stranger to such versatility: besides his work as a harpsichordist and conductor, he is also a composer.

Agsteribbe’s teacher, the renowned harpsichordist, pianist and conductor Jos van Immerseel founded the orchestra Anima Eterna (now Anima Eterna Brugge) – the name is a playful translation of his own surname – in 1987, to play concertos by Bach. It has since expanded and begun dusting off classical, Romantic and modern repertoire, which is to say: performing them as far as possible with original instruments and stylistic features.

In the time before Anima Eterna was founded, the cellist Roel Dieltiens was a valued partner for Van Immerseel. He remains one of Flanders’ leading soloists and chamber musicians. Incidentally, the Flemish school of early harpsichordists, of which Van Immereseel might rightfully be called the founding father (although we must not forget the early, pioneering work of the choir music icon Raymond Schroyens), is still producing many richly talented musicians: Korneel Bernolet, Bart Naessens, Wouter Dekoninck and Bart Jacobs, to name but a few, are keeping up the good work.

From Jos van Immerseel, it is only a small step to his good friend and fellow traveller Paul Van Nevel, the founder of the famous Huelgas Ensemble. Given Van Nevel’s field of study, the ensemble has a strong vocal orientation and continues to be one of the world’s leading specialists in Mediaeval and Renaissance repertoire.

In the vocal realm, we also encounter the much younger, more holistic and experimentally-minded ‒ and thus more flamboyant ‒ Graindelavoix, directed by the vocalist, musicologist and anthropologist Björn Schmelzer. They mainly focus on the still fairly undeveloped field of what was once Flanders’ most famous export product: mediaeval music. The fact that Schmelzer’s interests are anthropological and phenomenological as well as musicological means that Graindelavoix regularly engages with other traditions and styles.

Likewise focusing on the Middle Ages, the Ostend-based viola da gamba or mediaeval viol player Thomas Baeté is a regular musical partner of Graindelavoix, and a member of ensembles such as Mala Punica and La Rosa Enflorese. Since 2010, he has led his own highly international ensemble, ClubMediéval.

Equally open-minded is the vocal and instrumental ensemble Zefiro Torna, formed in 1996 on the basis of HIP principles, but now grown into a highly interdisciplinary and poly-stylistic group for which making music is a more of a humanist and socially conscious act than a purely artistic one. Dialogue with other cultures and collaboration with contemporary groups plays an important role in its work and philosophy.

New music

All early music was once new, and no artistic discipline stays alive without new forms of expression. Péter Eötvös once made the astute observation that HIP is also ‘a sort of avant-garde’. In this sense, it is not surprising that Flanders is also represented in the artistic vanguard.

A good starting point for an exploration of present-day performance practice is the legendary group Maximalist!, founded in the eighties in Brussels as a reaction to minimalism. The group was inspired by just about everything, but not least by Arte Povera, and its brief but powerful lifespan laid the groundwork for those who are still Flanders’ best known ambassadors of new music.

For example, the choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and her company Rosas come from this scene ‒ although they are not musicians, they have brought forth a great deal of music in co-productions. Maximalist! was also a forerunner of the no longer existing but nonetheless legendary group X-Legged Sally, with clarinettist and composer Peter Vermeersch; today he directs the Flat Earth Society, a wonderfully ‘meta’ brass band that cannot absolutely be categorised as classical music, but that does not matter, since it is difficult to fit it into any category at all.

Bl!ndman ‒ the exclamation mark is a tribute to Maximalist! ‒ was founded as a saxophone quartet by Eric Sleichim in 1988. Its path has taken it from pure avant-gardism, via crossover productions (around improvised film soundtracks for example), to remarkable projects involving Baroque (Bach’s organ music), Renaissance (with Paul Van Nevel) or mediaeval music (with Pedro Memelsdorff). Today, Bl!ndman is a music lab consisting of four quartets: sax, strings, brass and drums, with a hybrid line-up to boot.

Another offshoot of Maximalist! is the renowned Ictus ensemble, led, since its conception in the late 1980s by George-Elie Octors. It maintains a privileged relationship with many leading composers (including Reich, Aperghis, Romitelli…), foreign musicians and concert halls.

Quite a few of the Ictus musicians should also be mentioned in this summary in their own right. Big names include the oboist Piet Van Bockstal, a soloist with Antwerp Symphony Orchestra until recently and a sought-after soloist and ensemble player, and Tom Pauwels, a gifted guitarist with great conceptual and programming talents.

Also from Brussels, but of an entirely different nature, is Het Collectief. This group emerged from a chamber music quintet that took the Second Viennese School as a starting point in 1998. Since then, it has become a more flexible ‒ expandable ‒ ensemble of absolute world class. Thanks to the leading French magazine Diapason, its recording of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire – already a somewhat older project – has been rediscovered and praised as a recording that sets an absolute standard.

Contemporary music is also well represented in Antwerp. ChampdAction was founded in 1988 by the strongly electronics-oriented composer Serge Verstockt. While the ensemble initially focused exclusively on contemporary music, today it calls itself a ‘production company for new music, multidisciplinary music projects and audio art.’ ChampdAction maintains the strong bond formed at its creation with the cultural centre deSingel, the company’s literal and figurative home base.

Still in Antwerp, the pianist and conductor Koen Kessels has directed the HERMESensemble since 1999. Over the years, it has considerably expanded its field of work from what one might call the classic avant-garde of the 1950s and 1960s to crossover productions with other styles, genres and disciplines. Kessels combines the HERMESensemble with a hectic international career as the musical director of the Birmingham and Covent Garden ballets and a guest conductor at the Opéra national de Paris.

Het Nadar Ensemble was founded in 2006: its name is a tribute to the legendary 19th century caricaturist whose multidisciplinary, adventurous mindset inspires the ensemble. One of its artistic directors (alongside the cellist Pieter Matthynssens) is the engineer and composer Stefan Prins, which immediately gives an idea of the ensemble’s state-of-the-art inclinations. Nadar Ensemble has performed countless world premieres, and it has co-produced a Summer Academy for young musicians in Sint-Niklaas since 2010, in partnership with Matrix centre for new music in Leuven, whose documentation centre and educational activities are focused on art music since 1950, in Flanders and beyond.

Somewhere between Antwerp, Ghent and the Netherlands, we find the courageous and frankly incomparable guitar quartet Zwerm, which worked under the auspices of ChampdAction for its first few years. This is the avant-garde in its most light-hearted, spirited and inclusive form. Zwerm has worked with a very wide range of musicians, from intellectual newcomers like Serge Verstockt and Stefan Prins to the guitar legend Fred Frith and rockers Mauro Pawlowski and Rudy Trouvé.

Another very important figure in the Flemish new music scene is the cellist Arne Deforce. Once linked to both Ictus and ChampdAction ‒ not only as a performer but also as a developer of artistic trends ‒ he took off on a more distinctive solo course many years ago. Various composers have written for him, including Richard Barrett, Alvin Curran and Phil Niblock.

One of Deforce’s regular musical partners is Daan Vandewalle, taught by such people as the pianist, composer and professional intellectual Claude Coppens and Alvin Curran. His work in contemporary music has been a fixed feature for over 20 years. This applies no less to his fellow pianist Jan Michiels, a professor at the Brussels Conservatory who, however, rather than being dedicated to the latest contemporary music, focuses on the avant-garde that is now gradually becoming classical repertoire (including Ligeti, Kurtág and Boulez). Incidentally, Michiels is also very active in traditional repertoire, from Bach to Bartók.

In Ghent, we find the Spectra ensemble, founded by the pianist, conductor and composer Filip Rathé and the late Alvaro Guimaraes and led by Rathé. The ensemble is named after the Spectra Group, which shaped the electronic avant-garde in Ghent from the 1960s onwards along with the IPEM (Institute for Psycho-Acoustics and Electronic Music). Both institutions are closely linked to the illustrious names of deceased masters such as Karel Goeyvaerts, Norbert Rosseau, Louis De Meester and Lucien Goethals, as well as Philippe Boesmans, today the in-house composer at De Munt/La Monnaie in Brussels, the musicologist Herman Sabbe and Claude Coppens.

Ghent always has room for more when it comes to originality, contrariness and downright obstinacy, which is one reason why it is the home of the Logos Foundation, founded by the composer Godfried-Willem Raes, an ingenious builder of musical automata and unconditional musical progressive thinker, constantly engaged in a relentless struggle for the emancipation of music from virtuoso performers. The description that Logos gives of his mission, as precise as it is assertive, needs no explanation:

“The Logos Foundation is Flanders’ unique professional organisation for the promotion of new music and audio-related arts by means of new music production, concerts, performances, composition, technological research and other activities related to contemporary music”.

Composers

‘New music’ must be written before it can be performed. Here we will list the most prominent composers in Flanders, from established names and old hands to somewhat younger faces.

Luc Brewaeys died in December 2015, but we cannot fail to include his name here by way of tribute. He was a student of such masters as André Laporte, Iannis Xenakis and Franco Donatoni and our greatest symphonic composer, with nine symphonies, unforgettable ensemble pieces and brilliant orchestrations of Debussy’s Préludes for piano to his name. Among his students, Annelies van Parys should certainly be mentioned here as a highly original voice who couples mastery with fine intuition.

Raphaël D’Haene, a former professor of music theory and retired head of Brussels Conservatory, is more traditional in outlook but without doubt a prominent member of the Brussels cohort.

A radically different figure is the doyen of the Limburg scene, Frans Geysen, with a history of composing in both serial music and minimalism. He came up with a highly original variant of the latter, independently of developments in America.

Luc Van Hove, a long-serving teacher of composition at the Antwerp Conservatory, is still an established name: a constructivist holding the professional banner high. His colleague Wim Henderickx, a percussionist in a former life, made a name for himself with his ragas inspired by Hindustani music for orchestra and musical theatre, among other works. He has worked closely with HERMESensemble and Antwerp Symphony Orchestra, also devoting much time to music education.

A Ghent resident and professor at Ghent Conservatory, Lucien Posman cannot be compared to anything or anyone. He studied with Roland Coryn, the doyen of modern Flemish choral music, who is also still active. Posman is a self-proclaimed pos(t)-mannerist and a great fan and connoisseur of William Blake, to whose texts he has often composed, with an unmistakable emphasis on and love for vocal music.

Whilst in Ghent we must also mention the guitarist and composer Petra Vermote. She studied with masters such as the aforementioned Roland Coryn and Luc van Hove, as well as Frank Nuyts ‒ another invincible magician with notes who has certainly earned a place on this list. Vermote has written in virtually all genres for ensemble, but choral music holds a special place in her heart.

Speaking of choral music, we cannot ignore Kurt Bikkembergs. He is first and foremost a choir conductor, professor at the Lemmens Institute in Leuven and a great connoisseur of choral repertoire throughout history, but he also regularly makes contributions that are as clever as they are heartfelt.

The much younger pianist, conductor, singer and composer Maarten Van Ingelgem is particularly fond of vocal music. He is the son of the composer Kristiaan van Ingelgem, who has long been one of Flanders’ leading organists.

Kris Defoort comes from a completely different direction. He was once a classical recorder player, but became a celebrated jazz pianist and composer (in the artistic lineage of Gil Evans). He was later initiated into ‘classical’ composition and orchestration by Philippe Boesmans. Today, he is one of our leading composers, his most outstanding achievements to date being the opera The Woman Who Walked into Doors and the cycle Conservations / Conversations. After a period of forced inactivity, we are looking forward to his opera based on Richard Powers’ novel The Time of our Singing.

Interesting soundsmiths regularly emerge from ChampdAction, whose founder and inspirer Serge Verstockt was mentioned above. Two more names immediately spring to mind: Stefan Prins, also mentioned above, an engineer, pianist, composer, technologist and improviser with live electronics who is as universal as a contemporary musician can be, and Stefan Van Eycken, a musicologist and composer with a strongly phenomenological approach and interest, who has lived and worked in Tokyo since 2000 – and is incidentally an authority on fine whisky.

Last but not least – and fully aware that this list cannot be exhaustive – we would like to mention the pianist and composer Frederik Neyrinck, who recently returned to Ghent after many years living and working in Vienna. As a composer, he uses somewhat more traditional means and instrumentation than his colleagues mentioned above. With a great deal of success, as witnessed by the many collaborations and commissions he has in the pipeline.

Repertoire

Between ancient and brand new music is of course the regular, more traditional repertoire. Flanders has plenty to offer in that area as well. Partly supported by a widespread and highly accessible part-time artistic education system (DKO), well-trained musicians regularly make their way to professional stages at home and abroad. At the risk of not mentioning every one of them, here is a bird’s-eye view.

Flanders has a rich tradition of chamber music. This is represented at the highest level by the aforementioned quintet Het Collectief. Likewise from Brussels, and historically associated with Het Collectief, is the larger ensemble Oxalys (incidentally founded in 1993, a rather magical cultural year for Flanders, when Antwerp was the Cultural Capital of Europe). In terms of its spirit and the music it plays, Oxalys started out with the French chamber repertoire of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but has considerably expanded its range.

A very recent ensemble whose members are nonetheless old hands is the Taurus String Quartet: four seasoned chamber musicians who, after having played almost all other repertoires, decided to explore the royal genre of chamber music extensively.

The Goeyvaerts String Trio, based in Sint-Niklaas, has charted an impressive course in recent years. It focuses on the great repertoire of the late 20th century in particular.

I Solisti, the brainchild of top bassoonist Francis Pollet, was originally a woodwind formation that is at home in virtually every style. It has many premieres to its name and has been intensely involved with musical theatre in recent years. Most Flemish woodwind players of any significance have worked with I Solisti one way or another. Among them are the excellent soloists Piet Van Bockstal (oboe; see also Ictus, Antwerp Symphony Orchestra and many other ensembles) and clarinettist Vlad Weverbergh ‒ founder of the Antwerp ensemble Terra Nova and more recently often found in the company of the Prague Collegium 1704.

An exception to that rule is Benjamin Dieltjens, once a founding member of Het Collectief and one of the most well-rounded musicians in his discipline: he plays everything from baroque music on the basset horn to avant-garde on the modern clarinet, from concertos to orchestral pieces (at deFilharmonie) and chamber music. He forms a duo with his brother Thomas Dieltjens, and is without a doubt one of the most remarkable and respected pianists of his generation.

When it comes to wind players, we must surely mention the clarinettist Roeland Hendrikx, who enjoys widespread respect as an orchestral soloist (De Munt/La Monnaie, Belgian National Orchestra). He is also a teacher and chamber musician, and has led his own Roeland Hendrikx Ensemble for several years.

When it comes to the piano, we will certainly mention Julien Libeer, one of those rare musicians who are successful pianists without participating in competitions. He can call himself a protege of the great Maria João Pires. Another very talented near-contemporary is Yannick Vandevelde, who has even been praised by the living piano legend Elisso Virsaladze.

A few years older are Nicolas Callot and Lucas Blondeel, who, incidentally, form the aptly named Pianoduo Callot-Blondeel. Both pianists are also fervent accompanists and have been increasingly interested in historic pianos in recent years.

Another representative of this ‘Antwerp vibe’, as we might call it, is Nikolaas Kende, the son of the Hungarian-Belgian doyen Levente Kende and a professor at Antwerp Conservatory. He forms a chamber music duo with the excellent violinist Jolente De Maeyer.

With all this emphasis on exponents of the younger generation, we must not forget the more established names, who have frequently taught the former: we have already mentioned Jan Michiels; Piet Kuijken is above all interested in historic pianos, in keeping with the rest of his family, and Jozef de Beenhouwer is an international authority on Schumann and Brahms and a fantastic accompanist.

This brings us to Flemish vocalists of some renown. First, we must certainly name the soprano Ilse Eerens (for many years the protégée of the late Dutch contralto Jard van Nes), who is slowly and wisely working on a great career. Also much in demand is the soprano Liesbeth Devos, a very versatile singer in terms of styles and genres, who furthermore teaches at the Antwerp Conservatory. Let us also mention the especially exquisite and popular soprano Hendrickje van Kerckhove, the laureate of the International Opera Academy (IOA) in Ghent that is headed by the international opera director Guy Joosten.

There are male vocal soloists who deserve a mention as well. It would be difficult to ignore the career of the tenor Reinoud Van Mechelen, who is omnipresent on the international baroque scene. Respectively a little less and a little more than a generation earlier, we find the tenor Yves Saelens and the still active international bass-baritone Werner van Mechelen. Both are dedicated opera, concert and lieder singers.

The ‘vocal instrumental’ ensemble Revue Blanche, around the formidable soprano Lore Binon and a somewhat Debussian trio of the viola, harp and flute are also of a vocal bent.

Incidentally, singing is not the sole purview of famous soloists: the Vlaams Radiokoor has a cast-iron reputation. Historically it was a product of the national broadcasting service, with the premiering and promoting Flemish music as one of its tasks, but over the years it has taken on an increasingly traditional repertoire. Its recently appointed director is Bart Van Reyn.

A regular partner of Jan Michiels, Jozef De Beenhouwer and others is the violinist Guido De Neve, for decades an unconventional but significant figure on the Flemish music scene. The multitude of international violin soloists includes Yossif Ivanov, who in 2005 took second place in the Queen Elisabeth International Music Competition and in 2010 was the youngest violin teacher ever at the Royal Conservatory of Brussels.

Quite a few of our great musicians are somewhat hidden in orchestras. We have already mentioned the clarinettist Benjamin Dieltjens. His fellow clarinettist Jaan Bossier is a founding member of the renowned Mahler Chamber Orchestra and a member of Ensemble Modern. Apparently the Flemish air is particularly good for clarinettists: Annelien Van Wauwe’s early career with many major German and British orchestras is downright impressive.

The harpist Anneleen Lenaerts has become a permanent member of the Vienna Philharmonic, and also often plays in the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. We must not forget to mention the unforgettable trumpet player Manu Mellaerts, a soloist in La Monnaie Symphony Orchestra since as far back as we can remember. Here, he represents an entire school of excellent Flemish brass players, who usually do their excellent work somewhat in the background.

This brings us to the Flemish orchestras. Besides the National Orchestra of Belgium and La Monnaie Symphony Orchestra, there is of course Antwerp Symphony Orchestra led by Elim Chan, based at the recently completely renovated Queen Elisabeth Hall in central Antwerp; the Brussels Philharmonic under Stéphane Denève ‒ the former radio orchestra that is still linked to the former radio choir VRK (Vlaams Radiokoor), housed in the legendary boat-shaped Flagey building in Ixelles in Brussels; the Flanders Symphony Orchestra led by Kristiina Poska, resident at Muziekcentrum De Bijloke, which plays major venues such as deSingel in Antwerp and Concertgebouw Brugge as well as serving the Flemish hinterland; the strictly historically inspired Anima Eterna Brugge under Jos van Immerseel, in permanent residence at Concertgebouw Brugge; the chamber orchestra Le Concert Olympique under Jan Caeyers and the smaller Casco Philharmonic under Benjamin Haemhouts.

The conductor and composer Dirk Brossé must be mentioned here; he is a professor at Ghent Conservatory, musical director of the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia and a much sought-after guest conductor, not least for recordings of film music.

Organisers

All that musical beauty must also be properly organised and ideally be given a suitable place to resound.

The largest concert halls in Flanders generally do their own programming: Bozar at the Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels led by Paul Dujardin; Flagey, led by Gilles Ledure, also in Brussels, that houses the legendary Studio 4, world famous for its flawless acoustics; deSingel (Blauwe Zaal) in Antwerp, now led by Hendrik Storme; De Bijloke in Ghent, led by Geert Riem and Concertgebouw Brugge, with Jeroen Vanacker still at the helm. An exception is Queen Elisabeth Hall, mentioned above, in the new Elisabeth Center congress hall in Antwerp, which houses the Antwerp Symphony Orchestra but does not organise its own programme.

Flanders has a relatively high number of festivals, which also organise concerts. Many these are bundled under the name Flanders Festival, still a strong brand far beyond the national borders. Flanders Festival International and the Klara Festival, led by Joost Fonteyne, offer a programme of international favourites in collaboration with Bozar and Klara, the public classical radio station. Incidentally, Fonteyne put the Kortrijk edition of the festival on the map, called Wilde Westen and now led by Tom Vangheluwe.

Laus Polyphoniae in Antwerp is a well-regarded festival of early music. It is organised by AMUZ and led by Bart Demuyt, with a relatively small but ambitious seasonal programme in the prestigious St Augustine’s Church ‒ with HIP as the standard approach to its seasonal programme as well.

MA Festival, under the artistic leadership of Tomas Bisschop (also known as the manager of the vocal group Vox Luminis), is the Bruges branch of Flanders Festival and also a renowned early music festival. The festival is especially well known for the competition associated with it, which has brought many a future international star into the spotlight in recent decades.

In Leuven, we find Festival 20/21 (programmed by Pieter Bergé), a festival of standard repertoire that does not, however, go back beyond the year 1900 and Transit, a three-day event led by Maarten Beirens which is comprised almost exclusively of premieres.

In Ghent, Flanders Festival Ghent led by Veerle Simoens traditionally begins with the slightly wacky Odegand – or how else should we characterise an event comprising 60 concerts in one day at different venues in the historic city centre?

Another form of exalted insanity reigns in the Mechelen edition of Flanders Festival, under the name Lunalia. Maybe the city whose inhabitants once tried to extinguish the moon – as legend has it – have something to do with that, although the festival director Jelle Dierickx may also play a role.

In Limburg there are the perennially impressive season concerts at the CCHA (Hasselt Cultural Centre), programmed by Riet Jaeken for the last five years. The Basilica Concerts, a modest little festival originating in Tongeren, have grown under the artistic management of Bob Permentier (also a bassoonist with the Belgian National Orchestra) into the more ambitious, much acclaimed B-Classic, which also aims to be a lab and artistic breeding-ground, as befits a contemporary festival. With that explicit intention, it includes the Pressure Cooking Festival, the name of which speaks for itself.

The particularly glorious one-day festival Day of Early Music in the beautiful setting of the Landcommanderij Alden Biezen, also in Limburg, was reinvented and rechristened Alba Nova in 2014 by the director of Musica at the time, the composer, conceptualist, pianist and musicologist Paul Craenen, who now teaches at the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague. Alba Nova is still a one-day festival and still inspired by early music, but the reinvented festival focuses explicitly on the future and new music.

Alba Nova is an initiative run by Musica, the Limburg-based organisation for music education now directed by Esther Ursem. Whereas Musica is mainly – but not exclusively – focused on children, we find the Orpheus Institute at the other end of the educational spectrum. It is based in Ghent city centre and directed by the conductor and lawyer Peter Dejans and by Luc Vaes, a musicologist and pianist in the style and spirit of Claude Coppens. The Orpheus Institute is home to the very unique docARTES, a veritable doctoral programme for musical performers in collaboration with universities in Flanders and the Netherlands.

In relation to educational projects, we must also mention Zonzo Compagnie, the production company that creates shows for children. It is the brainchild of music theatre director Wouter Van Looy, whose highly original, interactive, child-sized festival that invariably presents outstanding artists, BIG BANG is certainly the best known.

Van Looy is also co-director of Muziektheater Transparant, a production company that provides a smaller, more agile counterpoint to the great vocal productions of Opera Vlaanderen ‒ with opera houses in Ghent and Antwerp ‒ and De Munt/La Monnaie ‒ the internationally renowned Brussels opera house under intendant Peter de Caluwe.

Last but not least, the Flemish do not programme and organise classical music in Flanders alone. Our expertise is also sought after abroad. In that context, we might mention Serge Dorny, who leads the Opéra de Lyon and will be leading the Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich from 2021 onwards; Xavier Vandamme, who manages the Utrecht Early Music Festival; and Lieven Bertels, who after his fourth Sydney Festival in 2016 and his stint as the artistic director of Leeuwarden 2018 ‒ the festivities celebrating the Frisian city as the cultural capital of Europe in that year – became the director of The Momentary, a new arts space in Bentonville, Arkansas, opening in 2020.

This last, somewhat brusque turn brings us full circle: contrary to the subject of this text, we have returned to the visual arts. And this is where we will have to leave things, dear reader, but rest assured that this is definitely not all. We still suffer from a delightful embarras de choix.