The dream collaboration. Possible pitfalls in the creation of collaborative projects with the MENA.

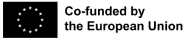

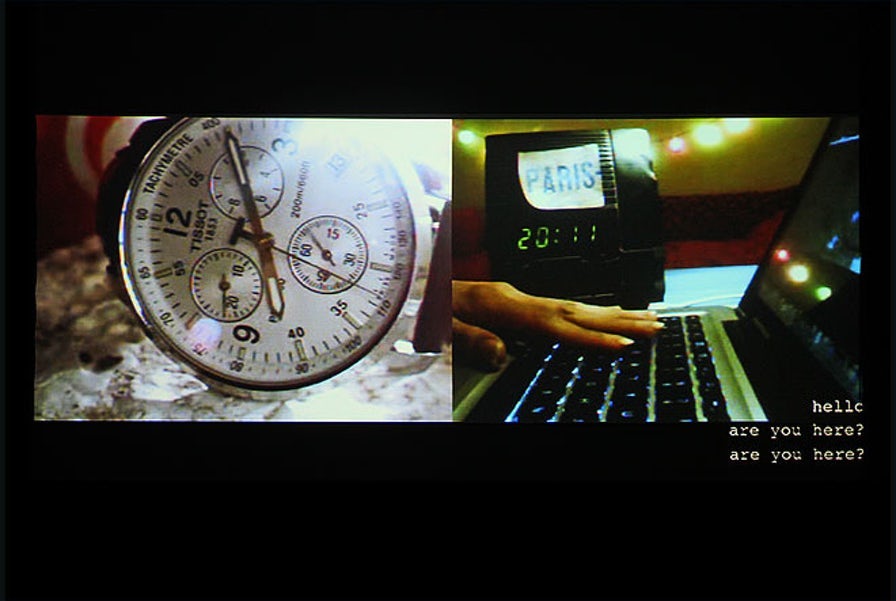

I remember it like it was yesterday. I was standing right in the self-proclaimed centre for art and media ‘Argos’ in Brussels, looking at choreography that was performed simultaneously in Paris and Tunis. By aligning the precise framing of both spaces and by synchronising time in Paris and Tunis, the Sofiane and Selma Ouissi managed bridge any geographic or time-limited restriction to create a third, albeit virtual space, which succeeded in bridging any possible spatial or temporal limitation. Paris and Tunis melted before my eyes into a new third free space in which both dancers pursued their lived – almost symbiotic – choreography.

The online dance performance Here(s) of the inseparable artist duo Selma and Sofiane Ouissi took place during in October 2011 during the opening of the ‘Meeting Points 6’ festival, an initiative of the ‘Young Arab Theatre Fund’. Sister and brother Sofiane en Selma gradually formed from one performance to the next a single body through their shared practice as dancer and choreographer, until Selma moved to Paris and Sofiane was left alone in Tunis. Thanks to real-time video communication applications they managed to bridge the distance between both metropolises and thus found a way to reconstitute their shared practice and reflection. During Here(s) they share this initially rather practical communicative bridging, which gradually grew into a full-fledged choreography.

In what follows we will delve deeper into the question how this performance touches on the essence of current global challenges in a clear, refined manner. Subsequently, the Meeting Points festival, in which this performance took place, will be seized in order to linger on the necessity to review existing practices transnationally, to anchor them sustainably and lastly to interweave them from below with other relevant local diasporic practices. Throughout this exercise I hope to touch in between the lines upon possible pitfalls in setting up collaborative relations with the MENA region from the privileged position that the capital of Europe, at least for now, still enjoys. The main challenge will be to understand the apparent contradiction between different types of global and local dynamics and thus to discern the importance of their inevitable entanglement and to take into account its political implications. A necessary exercise, certainly now Tunisia is included in the Creative Europe programme.

Update the international

As the title Here(s) already suggests, the live performance relates to the virtual embodiment of plural localities. If today we speak about ‘here’, however, we are still speaking about a singular locality that is opposed to another clearly delineated locality, ‘there’. In other words, it is not yet quite grammatical to use ‘here’ in the plural. The trouble with pronouncing the plurality of ‘here-s’ in the title thus refers in itself to a troubled understanding of changing relation to time and space. Moreover, it is important to underline that the proposed recalibration of time and space in the performance, is not taking place in a power vacuum. By connecting Paris with the capital of its former colony Tunis, the ensuing third space, in which the choreography unfolded, fundamentally challenges the way in which we understand and represent our entangled and mutually constitutive but conflictual histories and geographies. The postcolonial border that is crossed digitally back and forth in the course of the choreography is in reality still sharply cutting our humanity today. Let’s just think for a second about the daily horror of the often fatal informal movements on the funerary waves of the Mediterranean Sea.

his is not a normative question nor a judgement, but a question that points to an important pitfall. When partnerships are launched from the European continent with actors, networks and organisations from the MENA region, one often still thinks about what we ‘here’ can contribute to the arts sector ‘there’.

The changing experience of time and space was not only the central subject of the online choreography and the broader Meeting Points festival, it is a phenomenon that more and more people experience in their everyday life. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the final breakthrough of ongoing neoliberal globalisation, more and more people are moving from more and more places to more and more places. In about two hours you can go from ‘here’ in Brussels to ‘there’ in Tunis. Moreover, through video communication technology, it has become possible – as we saw in the performance – to be simultaneously present ‘here’ in Tunis, ‘here’ in Paris and ‘here’ in Brussels. This “plural simultaneity” determines the way in which the globalised world is shaped in practice today – day in day out. Mobility has not only radically increased in terms of quantity, it has also undergone a profound qualitative change. Today, people whose migration has been formalised and regularised, no longer need to choose per se whether they live ‘here’ in Brussels or ‘there’ in Tunis, they can live ‘here’ and ‘there’ simultaneously as new applications. made bridging time and distance increasingly user-friendly. However, this changed mobility remains relative to the legal papers one needs to bridge the euro-centric boundaries that divide the world in nation states.

The choice between both is thus essentially only a matter of historical constructions and their related rusted anachronistic ideas and concepts and thus of political power. What is central in this “plural simultaneity” is the question what ‘Paris’ exactly means in ‘Tunis’ or ‘Tunis’ in ‘Paris’. This question is however difficult to answer without taking into account the concrete geographical imaginary connotation of both cities, their respective political role as floating signifiers and therefore also their function as historical or cultural metaphors in a postcolonial and sometimes enduring colonial context. The same reasoning also holds for perhaps easier examples such as Palestine or, today, Kabul or Damascus. It is of crucial importance – if we want to update our understanding of international relations – to constantly re-iterate the question, what for instance “Palestine” signifies metaphorically in Brussels but also what “Brussels” denotes in Palestine and how both mutually relate. Or what “Damascus” stands for in Brussels and what we insinuate when we speak about “Brussels” in Damascus. How do “Brussels” and “Damascus” mutually relate to each other?

It is of crucial importance – if we want to update our understanding of international relations – to constantly re-iterate the question, what for instance “Palestine” signifies metaphorically in Brussels but also what “Brussels” denotes in Palestine and how both mutually relate.

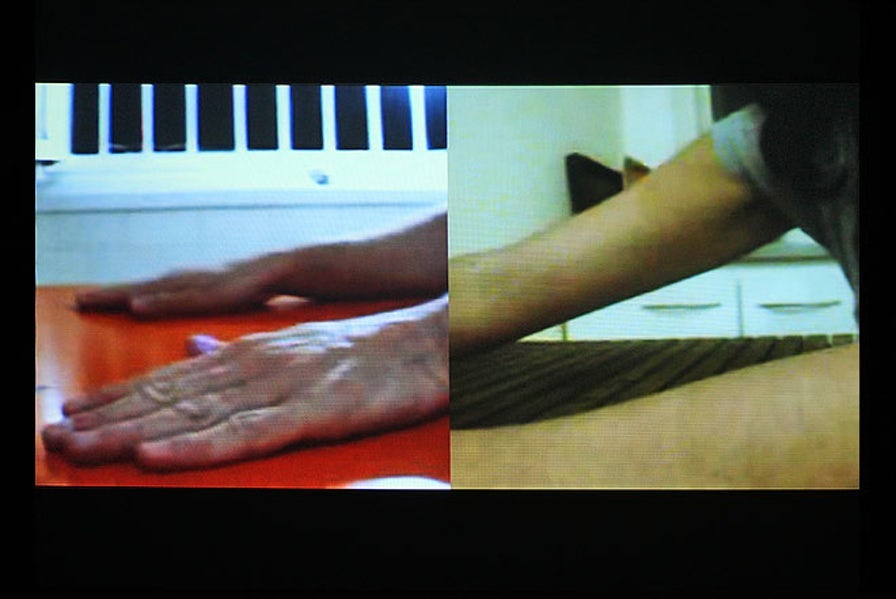

These are essential political questions, as more and more metropolises have become “Majority Minority” cities, cities where the majority of the population is part of a minority in a context of accelerated globalisation, generalised migration and thus of entwined proximity but also of growing inequality and conflict. Although hundreds of people drown each month in the waves of what we can call “The Red Mediterranean”, more and more people live in an urban context that reproduces global dynamics both geographically and historically on a local scale at ever greater speeds and in greater concentrations – a phenomenon that critical geographers such as Doreen Massey conceptualized as “time-space compression”. In these global metropolises the ‘here’ and ‘there’ are fundamentally and completely entangled. I believe that it is in that complex and sometimes conflicting intertwining of what Edouard Glissant aptly named the “Tout-Monde” that all our future challenges lie, not least when wishing to set up new forms of collaboration between the European continent, North Africa and the Middle East.

No matter how familiar Ryan Air, WhatsApp and Skype sound to our ears, that plural simultaneity and relative mobility and time-space compression we just evoked, remain challenging to understand – and the title of the performance of Sofiane and Selma Ouissi – difficult to pronounce. Here(s). The world Edouard Glissant is talking about is no longer only made ‘here and now’; it is the plurality of interwoven localities and temporalities that shapes today’s world. Although both places are geographically and historically almost completely intertwined, we are still convinced that Tunis lies at a safe distance from Paris. When a demonstration is held in Brussels against the ongoing colonisation of Palestine, when an attack takes place in the heart of Paris or when the Turkish diaspora has to vote a Turkish referendum in Brussel, some are accused of importing conflicts from the Middle East. Increased mobility, digitisation and globalisation have not only accelerated the migratory movements, but have also ensured that political ideologies, events and therefore also conflicts ‘abroad’, have a direct impact on the ‘interior’, and vice versa. Moreover, the intractable conviction lives on that that Tunis and other metropolises in the Global South have “to develop” along an imaginary line drawn by the progressive economic, technological but also moral and political evolutions in Paris or other metropolises in the Global North. Self-declared superiority was never a taboo here, on the contrary.

The world Edouard Glissant is talking about is no longer only made ‘here and now’; it is the plurality of interwoven localities and temporalities that shapes today’s world.

Local and global movements are becoming increasingly interwoven and fundamentally challenge our current understanding of artistic work and international cooperation. Global conflicts are intensifying and intruding in the safe environment of the arts centre and are challenging the autonomy and responsibilities of the arts. How must the arts deal with this rapidly changing, conflictual political reality? What at first sight seems to be none of our business appears upon closer inspection to be unfolding on our doorstep. Conflicts are not ‘imported’, but reproduced worldwide – always anew – on a local scale. The increasing conflicts and wars since 9/11 in countries with a Muslim majority are not only bringing about political destabilisation and unprecedented human suffering and destruction ‘there’, but are also a powerful challenge to society ‘here’ in countries with a Muslim minority. Questions about the autonomy of the arts and the creation of international collaborations are thus becoming not only radically more complex, but also ever sharper and more conflictual. What does it mean to be an artist, to facilitate artists or to set up international collaboration projects in this -at times contradictory and disruptive -but challenging contemporary context?

We have almost forgotten, but it was only six years ago that the world shook to its foundations after the Tunisian masses took to the streets to overturn their dictator, then still supported by the international community. This unexpected popular movement consequently triggered a collective ‘awakening’ from Cairo, Barcelona and Athens via Kampala, Istanbul and Tel Aviv to Dakar, Damascus and even Wall Street … of all places! For a moment it seemed as though the dominant identity politics had suffered a fatal blow and that political space finally emerged to expose and alter hegemonic power balances and to annihilate historical relations of exploitation. For a moment it became clear that this was not a clash of civilisations, but of geopolitical and economic interests. Today, alas, our opinions, historical convictions and imaginary geographies, which appeared to have been overturned at the time, seem more than ever to be firmly in place. Like never before, our political representatives are catalysing our fears in the ever sharper delimitation of imaginary borders, enemies and the construction of walls. Not only the notorious wall between America and Mexico, but also the wall in Calais less than 200 kilometres from Brussels, or the wall between Tunisia and Libya, Turkey and Syria or indeed Israel and Palestine, are not only reassuring the alienated mass; they materialise – down to the bone — the inherent contradictions and indignant imbalances of neoliberal globalisation.

The main challenge will be to understand the apparent contradiction between different types of global and local dynamics and thus to discern the importance of their inevitable entanglement and to take into account its political implications.

With both feet on the ground

An update of our political notion of international relations to the pace of our contemporary globalization is urgent. Through a renewed understanding of the internal through the characteristics of relative mobility, time-space compression and plural simultaneity, we will now re-direct our attention to the grounded and concrete challenge of deepening existing collaboration trajectories between Brussels and Flanders on the one hand and the Middle East and North Africa in the broadest sense. Given the seriousness of the challenges we face today, it is necessary, instead of reinventing the wheel, to focus on what has already been achieved in our dynamic arts landscape – starting with the initiatives for which the above political and social context is not a shocking reality check, but a daily practice. For this it is necessary to look at what partnerships have already been established and especially how we can look back on them critically.

We could re-open with a sense of nostalgia the programme leaflets of Masarat in 2008 or Daba Maroc in 2012. Two season-filling cultural initiatives where, among others, the ‘Halles of Schaarbeek’ made the connection between our capital and artistic movements in respectively Palestine and Morocco. Or that of the more recent Moussem Cities, where our beloved nomadic arts centre connects the artistic dynamics in Tunis and Beirut and soon also in Casablanca with a Brussels audience. Or the intensive and sustainable commitment of the former artistic team of the KVS in Ramallah and its surroundings, which brought about effective landslides in the local performing arts and internationally and has now luckily merged into Connection vzw, the organisation that continues the international work of the former team of the KVS. Let’s certainly not forget the pioneering role of the Kunstenfestivaldesarts in this light. And lastly perhaps, we could also dare to open the booklet of less successful stories such as the whole Flemish Daarkom disaster and its painful if existing collaboration with the more or less like-minded French-speaking Espace Magh, which by contrast has managed to set up meaningful projects in collaboration with various players from the Maghreb region and its diaspora here in the capital. A necessary exercise certainly now Daarkom is transforming into the somewhat more humble and hopeful Darna.

Given the seriousness of the challenges we face today, it is necessary, instead of reinventing the wheel, to focus on what has already been achieved in our dynamic arts landscape – starting with the initiatives for which the above political and social context is not a shocking reality check, but a daily practice.

Unclassified Tunis

This contribution will however limit itselve to the critical reading of one story, which ties in nicely with the introductory virtual performance. ‘Here(s)’ took place during the vernissage of Meeting Points, a contemporary transnational arts festival initiated by the Brussels Young Arab Theatre Fund, recently renamed Mophradat aisbl. Argos and the KVS opened in the aftermath of the promising spring of 2011 their doors in Brussels to the sixth edition of the multidisciplinary festival, curated at the time by Okwui Enwezor. The programme of the festival was caught up by the global protest movements that had broken out that year. From the Arab Revolutions over the Indignados to the Occupy movement, not only were authoritarian regimes and their allied corrupted economy of the 1 per cent radically questioned, but also rusted orientalist concepts and other imaginary geographies took a terrible knock. The works on show revolved around the given theme, ‘Locus Agonistes’. Caught up by radical political events, Meeting Points became an exploration of various aesthetic strategies to represent the meeting points between agonistic localities through three distinct ‘Flash Points’. The Middle East, North Africa and Europe, the three areas where the festival took place locally, were thus no longer conceived as geographically distinct entities, but as three fleeting constellations or ‘Flash Points’ for well-reasoned and motivated disagreement. The meeting points between these three randomly connected constellations are put forward as sites for potential societal productions.

Meeting Points is a recurring biennale and is always curated in and across seven different cities: Amman, Athens, Damascus, Beirut, Berlin, Ramallah, Cairo, Tangiers, Tunis and Brussels. It is systematically organised in cooperation with local partners, working in close collaboration with independent spaces, artists, organisations and networks. It fully incorporates its transnational character in its structure and deliberately chooses not to have a central city where all activities take place, but generates a simultaneous artistic discourse and practice across multiple centres and cities. The festival is already in its eighth and last edition, but it is on the fifth edition, curated by Frie Leysens and Maha Maamoun, the present argument will be further elaborated. It is after all during this fifth edition that the ‘Unclassified programme’ was launched.

‘Unclassified’ was an initiative of the Meeting Points festival organized by the Young Arab Theatre Fund that challenged curators from six different cities to curate an artistic programme with and for the city in which they lived. The idea was to set up a well-balanced dialogue between the travelling programme of Meeting Points and the various local artistic realities in Alexandria, Amman, Beirut, Cairo, Damascus and Tunis. The resulting projects were very diverse both formally and in the way they related to the local urban contexts. Together they formed a profound reflection on the position of artists and place-bound artistic productions not only in the direct relation with their audiences, but also in relation to the inhabitants of the various cities and the specific urban and cultural landscapes in the MENA region.

Unclassified was announced with a healthy dose of doubt about its sustainable character. I do not know what the consequences were of the Unclassified call in Alexandria, Beirut, Cairo or Amman. This contribution is limited to what the call of Meeting Points, at the time still under the direction of Tarek Abou El Fetouh, has brought about in Tunis. As, what began as an answer to the project call in 2007 has today grown into Dream City, a biennale of contemporary art in public space that speaks to the imagination.

With the Unclassified program, artist duo Selma & Sofiane Ouissi found the means to finally launch their long-dreamed urban interventions. In Mai 2006, Selma Oussi was invited to present live the performance “STOP . . . BOOM” on RTCI (Radio Tunis Chaîne Internationale). On the spot she decided to conclude the interview by spontaneously calling artists to march in the streets to defend the arts in Tunisia. The red lights in the studio interrupted her statement, signaling the live stream was cut. A stripe of music abruptly ended the interview. As the following day the radio host was fired, both Selma and Soufiane were afraid this incident would also have repercussions on their safety. However there was no space for doubt when in the summer 2006 curator of Meeting Point festival Frie Leysens invited the duo to answer her “Unclassified Call”. The spontaneous call on life radio was translated in an intention note proposing a choreographic protocol in public space that would materialize in the the first edition of Dream City. What was initially conceived as a reflective artwork in the public space of the medina, as a choreography to make artists walk in the streets to defend art, eventually grew out to become an unstoppable artistic movement.

From the start it was conceived as a space-time to rethink artistic practices from a post-disciplinary perspective in an authentic dialogue with blind spots in the old medina in Tunis. Through a collective and participatory artistic practice, the festival dreams from below of a possible and lasting future for and with the city, its inhabitants, users and passers-by. It was set up and produced without any official application or permit. Which in itself was particularly brave in the context of a dictatorial regime where it was forbidden by law to move in the intensely controlled public space in groups of more than three. The strong gesture initiated by Sofiane and Selma brought too many artists in movement to be stopped by the police. The festival was welcomed by many as a respite in the suffocating routine of autocratic conformity, but also as a clear opening and a breakthrough in an otherwise also relatively obedient and closed artistic landscape. Even Though it was never conceived as a festival, but as an artwork, a second “edition” imposed itself by a growing demand of artists for a federating and reflective platform.

With the second edition in November 2010, the festival deepened its initial principles and objectives. The programme elaborated on the theme of the dream city, but added to the whole some subversivity by making its intentions explicit to reclaim the street as a symbolic space, to divert its symbols and question its limits. By hindsight, the festival seemed to be permeated by an accurate premonition about what the country and the world were to expect. Through both the artistic practices facilitated in public space and the discourses sent into the world, they emphasised the need for an ‘individual and collective awakening’ and this long before the start of the revolution.

The festival was welcomed by many as a respite in the suffocating routine of autocratic conformity, but also as a clear opening and a breakthrough in an otherwise also relatively obedient and closed artistic landscape.

The first edition of the festival since the start of the revolution, only took place in 2012. After mobilising revolts had managed to jointly wipe the rusted dictator off the map, various controversies related to the newly acquired freedoms and the unanswered urge for dignity imposed themselves. The festival was therefore compelled to formulate the question whether artists can still dream up their world in an age when their freedom is being threatened in the depths of their existence.

Since 2011 some artists have indeed been threatened by various violent attacks by Islamist activists in Tunisia.. The high point was the iconoclastic attack on the exhibition Le printemps des arts in El Abdellia Palace in Tunis, where various artworks were destroyed and burned, after which a number of violent demonstrations in the country left one dead and hundreds of injured. In the wake of these attacks, the binary division between secularism and Islamism settled as the main frame in which the political situation was understood. Artists were moreover a priori pigeonholed in the secular cubicle, which only seemed to confirm the supposed incompatibility between art and Islam, modernity and tradition.

By contrast, the third edition of the Dream City festival comprised a well-balanced programme in the public space of the medina of Tunis. It managed to intelligently divert the polarising secular-Islamist pitfall and brought forward a new critical and poetic third space in which the social and political causes and consequences of the revolution and their relation to freedom could be broadly reconsidered. Artistic interventions were once more explored and redefined as driven by a combative but reconciliatory force in a polarised society. To preserve its autonomy in public space and to avoid any form of political exploitation, the participatory and inclusive character of the interventions was even further deepened.

For the last edition in 2015, the revolutionary storm had largely subsided, law and order had more or less been restored. It was the ideal opportunity to raise future-oriented and promising questions about the role of art in maintaining, questioning and manipulating social relations. For this last edition, artistic directors Selma and Sofiane Ouissi were assisted by Jan Goossens as guest curator. Dream City further oriented is international facet in the direction of the African continent and the Middle East rather than towards the ‘West’ or the ‘North’. For the first time in a long time, the discussion emerged again about the possibility of a continental bob marley aesthetic. The question as to how the urban aspect of the proposed artistic interventions can mutually connect local and global issues was further explored.

Dream City further oriented is international facet in the direction of the African continent and the Middle East rather than towards the ‘West’ or the ‘North’.

Unclassified Brussels?

Besides ‘Unclassified Tunis’, the Meeting Points festival also stimulated artistic impulses in Alexandria, Amman, Beirut, Cairo and Damascus. In Athens, Berlin and Brussels, however, the work of artists from North Africa and the Middle East was only shown from a receptive point of view. When we recall our updated understanding of the international, the question indeed imposes itself why no ‘Unclassified Athens’, ‘Unclassified Berlin’ or ‘Unclassified Brussels’ was set up? This is not a normative question nor a judgement, but a question that points to an important pitfall. When partnerships are launched from the European continent with actors, networks and organisations from the MENA region, one often still thinks about what we ‘here’ can contribute to the arts sector ‘there’. It is rare that both geographic poles that distinguish ‘us here’ from ‘them there’ are seen as mutually constitutive.

On the contrary, the presence of various international cultural institutes and NGOs ‘there’ is hardly ever problematized. Just think of the innumerable initiatives of the ‘Institut Français’, ‘British Council’ or ‘Goethe Institut’. While the opposite is perhaps even unthinkable. So no, this is not a plea for the establishment of a Flemish Council in the MENA region, on the contrary. Convincing you to set up a MENA Council here in Brussels will probably require more than the arguments that could be brought up within the limits of this contribution. This final remark wants to let the question linger as to why no curator or curatorial collective was challenged in for instance Brussels to compose, outside the existing policy structures and the regular arts field, an artistic programme with and for the city, with and for diasporic artists from inter alia the Middle East and the Maghreb?

The resulting dialogue between the central programme of Meeting Points and the artworks that would have emerged out of an artistic engagement with the various informal local urban networks in Brussels, would certainly have appealed to the imagination. That is surely beyond any doubt, right? Brussels is brimming with talent ‘here’, and yet these creative ‘raw materials’ apparently are not as easily welcomed as the artistic – maybe more exotic and less familiar and demanding – potential ‘there’ in the Middle East and North Africa. Although Brussels is a global metropolis where the ‘here’ and ‘there’ are fundamentally interwoven, artistic talent growing on our doorstep remains unnoticed – under the radar of the most important players in the arts sector. The main blind spot in the whole dream international collaboration lies therefore in the meeting points, intersections and connections that we can make between, on the one hand, the MENA ‘here’ and the MENA ‘there’. After all, it is in this interwovenness that lies the potential to go beyond the advancing bifurcation that is imposed on us today on both sides with catastrophic conflictuous even deadly consequences.

When partnerships are launched from the European continent with actors, networks and organisations from the MENA region, one often still thinks about what we ‘here’ can contribute to the arts sector ‘there’.

Artists without borders

The trajectory of Dream City biennale informs us that a generous but thoughtful impetus of a transnational organization “here” in Brussels can have a structural impact “there” in North Africa, if at least it can quickly make itself redundant. When we take into account the plural simultaneity, relative mobility and time-space compression so characteristic of our globalised world today, the local anchoring of a transnational arts festival emerges as a sine qua non not to become an object of political instrumentalization.

With the ‘Unclassified’ programme, Meeting Points has been able to give an impulse, beyond the formal policy structures, to the right collective to develop from below an artistic platform that managed to change the arts sector in Tunisia profoundly. Moreover, this has all been possible in a context of a deeply rooted autocratic regime. With an enduring flow of different and diverse artistic interventions in public space, Dream City managed to challenge a dictatorship in a powerful manner. As it was not tied to any policy framework, it could also adapt quickly to the rapidly changing post-revolutionary situation and grow into what it has become today. To what extent the collaboration between Meeting Points and Dream City remained limited to the initial impulse or whether a more systematic collaboration occurred is something I unfortunately do not know and which can be the subject of further research.

It is thus certainly worth further exploring the archives of the ‘Unclassified’ programme with the question how ‘The Young Arab Theatre Fund’ set to work in order to make itself redundant. Further research in this direction will proof productive in answering the question how organisations can facilitate international cooperation from below. However, the genesis of DC in itself tells us already enough about how we can deepen existing transnational collaboration trajectories between artists and cultural workers “here” and “there” in the current political context.

The dream collaboration thus goes beyond the alleged need to set up the right initiative ‘here’ or ‘there’, but starts out with the mission of reinforcing the various existing initiatives and especially the meeting points, intersections and connections between the various existing initiatives simultaneously ‘here’ and ‘there’ .

Just as theatre company ‘Action Zoo Humain’ made clear during its latest performance, Join The Revolution, the question cannot be raised as to what we can do ‘here’ for the arts sector ‘there’ in Tunisia without challenging ourselves ‘here’ to occupy the stage ‘here’ too and thus without becoming an ‘artist without borders’ and converging into the worldwide revolution that is tearing down the walls maintaining our colonial histories and their related imaginary an real conflicting geographies. That destroys the political difference that remains between the world “here” and “there”, and creates space again for difference, justice and equality.

The dream collaboration thus goes beyond the alleged need to set up the right initiative ‘here’ or ‘there’, but starts out with the mission of reinforcing the various existing initiatives and especially the meeting points, intersections and connections between the various existing initiatives simultaneously ‘here’ and ‘there’ . In the hope that the Mediterranean Sea will soon be able to be crossed from both sides on an equal footing.