Blogging from the Return of the Fantastic Institution at BUDA Kortrijk

In February 2017, BUDA Arts Centre in Kortrijk brought together artists, theorists and directors from all over Europe to discuss the possibility of another artistic institution. One that would be more permeable to it’s own political or socially engaged artistic program and would finally do what she preaches. This symposium was called the Fantastic Institution, a 3 days discussion platform between reality and fiction.

One year later, we are back for The Return of the Fantastic Institution. Are we anywhere more fantastic than before? Or not at all? In any case, it is interesting to ”stay with the trouble” a little bit longer and hammer this question once more.

Day #1 – Mirrors and Mirages

by: Delphine Hesters

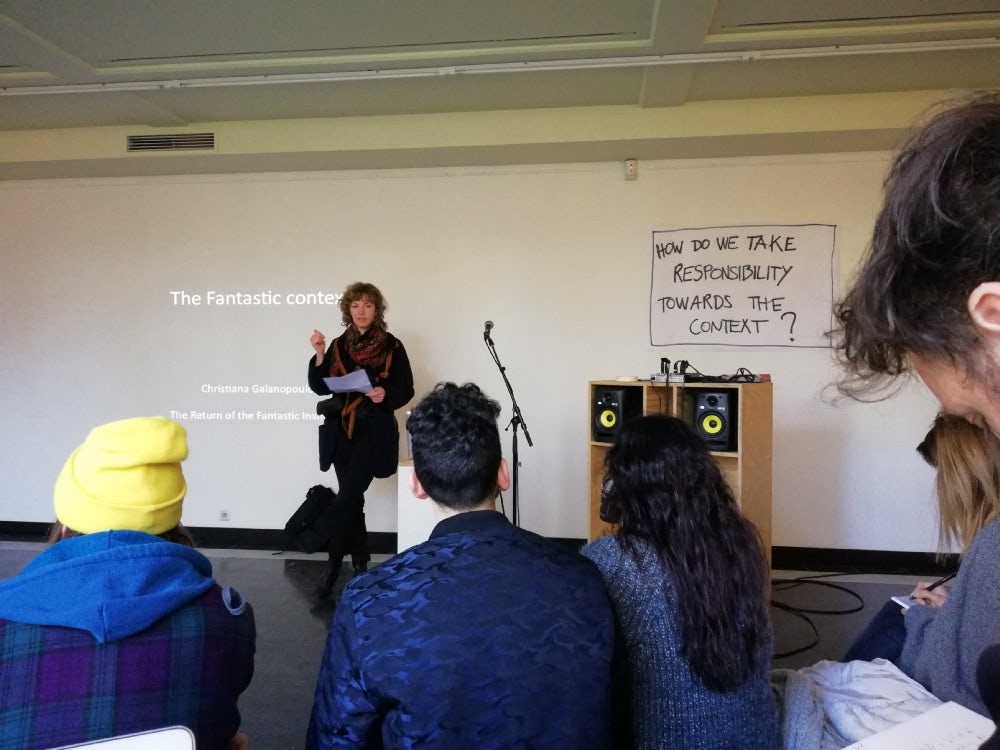

The first day of the gathering at BUDA aimed at tackling the question: “how do we take responsibility towards the context?” Here an attempt at drafting the collective answers that we almost formulated, based on selective listening and knitting together stimulating insights of several contributors, in three parts.

Part 1. We are the context

Christiana Galanopoulou from MIR festival in Athens kicked-off by stating: “if we want justice, freedom and accessibility in society, we need to work on it within our institutions.” Also realizing that as long “as our institutions are part of a capitalist system, they are funded by it to be used by it.” A statement that can be lifted to a more general level: the parties you get funded by, use you for their own purposes. How to align your values and convictions with the build-up of your institution and the way it operates? ‘How can we walk the talk?’ will be the line most repeated in the days to come. “If you neglect, deny or underestimate the context (local, social, political), it can endanger your thinking about the content of your program or make it untrustworthy. But it also neglects all political, emancipatory potential of your program,” Marta Keil phrased it.

In the discussion about which topics to tackle in the parallel working groups, we decided to keep two zones of questions separate: “how to take responsibility for society and respond in a proper way to the realities of the outside world?” versus how to take responsibility for what the institution set out as a goal, as a contribution to the world, and –related- take responsibility for the people within, for healthy conditions.” We went along with this proposal, while Mai Abu ElDahad from Mophradat already from the outset corrected that “how we build our own institutions is the model for how we build our context, the society.” It mirrors the society and vice versa. Maybe we are not yet ready to fully grasp the meaning and consequences of that statement?

It is simply impossible to take the institution as a neutral ground from which to build a relationship with the context. We are the context.

Part 2. We are all eyes in the same head

The group of participants of the Return of the Fantastic Institution is very diverse. Some work in larger institutions with more or less decent means (financial and other) in countries with long traditions of public funding for the arts. Others are sustaining artistic practices or building organizations on virtually no support or in spite of adversity from political powers. Are we in the same conversation? Isn’t the challenge of changing institutions from within, as they are not (anymore) in line with the values and goals they proclaim, very different than the challenges of setting up smaller institutions built on different grounds? It isn’t a coincidence that the answer of several of the participants somewhere along their personal trajectories has been leaving an institution in order to set up something new, start from scratch. As Christina Galanopoulou put it: “as long as we are waiting for the system to collapse or for the big change, nothing will happen. I would propose to make little independent fantastic institutions in a different space.”

However, the dichotomy between (fighting) inside or outside the system is a false one. There is only the inside of the system.

As artist Sarah Vanhee pointed out: “we are all part of the system. I was able to perform at MIR in Athens, because I was well paid the week before in Sweden. These money flows of the larger system make it happen.” Maria Hlavajova of BAK invited us to think up ways to get out of the position of ‘being against’. We should find ways to not be ‘with it’ nor ‘against it’ — ways of being ‘in spite of’. We should not be ‘hijacking’ the institutions, but we should institute otherwise. (Not being paid for your work is not hijacking the system, it is mostly (self-)exploitation.)

Part 3. On mirages — performing the institution

“We have to create a mirage of scale for the politics. Pretend that we are actually succeeding in ‘being a platform for the local scene’, while in reality, we are a fragile raft.” Alexander Roberts from the Reykjavik Dance Festival created an image that many of his partners in the conversation recognized very well. However, this is not just a moral issue of having to face the gap between the image and reality. This performance of the institution, the mirage, is setting standards. The speculation becomes the condition. Hence, the exhaustion that comes with keeping up the facade becomes the standard. It is exactly this observation, that we can no longer keep up the façade while the back is collapsing, that made Anne Breure and her partners at Veem House for Performance in Amsterdam decide to no longer play along, and to turn Veem into the ‘100day House’. Not as a solution or a model for other institutions, but as a way to reveal the problem and to invite the whole field to look into the mirror.

Next to ‘how to walk the talk’, I expect another question to rise more often today and tomorrow: ‘how to move away from the demands of productivity?’

Being passionate people, all the participants in the room love to work and love to produce art. This is not about not producing. It is about the demands and values put onto ways of producing, the products and productivity in itself. Sarah Vanhee: “as an artist, I want to produce more. But it comes with an apparatus that is super heavy. Which actually makes me want to produce less.” That weight is not just the weight of what it takes, practically, to set up a professional performance. It is also in the kind of valorization which comes with certain kinds of productivity, formats and temporalities that are recognized by institutions; artists and artistic work that is therefore valued and considered credible. Hence, one way to proceed is to start breaking down the values we attach ourselves to participation in certain parts and ways of the system. ‘Demythicizing passion’, for one, has been put on the table several times as a task for all of us.

What a curious picture it is, looking at it from the outside. Peggy Pierrot helps us observing. Art institutions running on an ideology built on engagement, passion, on not counting hours… while inside, there are so many different people. Also people who do count hours, who do take up a regular job from 9 to 5. Some people get paid and some not. Some are protected by a union and some are not. Some are in it for the symbolic capital and some for earning their monthly wage. Curious gaps are running through these institutions, between people sitting next to each other at the lunch table. How do you deal with this? How do you organize that?

The question for today, day 2: “how do we work together?”. Stay tuned.

—————————————

Day #1 – How do we take responsibility towards the context?

by: Marine Thevenet

How does an art institution take responsibility within a specific context and towards a specific community? for how long can you run on enthusiasm? at what point do you need recognition ? what if the socio-economic or political context is undergoing drastic change? how does that influence your responsibility, enthusiasm and recognition? In what ways might those changes pile up over the years, leading to potential and perhaps radical turns in an institution’s life and identity?

Christiana Galanopoulou from MIR festival, Athens, reflected on a Fantastic Context, with the example of the magazine ANTI, created in 1976, 2 years after the end of the dictatorship, when the Greek society was redefining itself. In a context where no big contemporary art institution was existed, Anti became the forum where one could express a new utopia for the arts. It felt the moment, the right context, for the Greeks to define their (utopic) fantastic institution in a political journal: where institution of contemporary arts has to be led by artists, where the moderator can only be the audience, where art will be part of what’s happening in the work, and most of it, with the aim of not becoming a museum…

Taking the example of Pompidou centre building at its opening in 1976 — fruit of the imagination of young architects Rogers and Piano, Ganalopoulou showed how much design and architecture can be the reflection of the behaviour of an institution, and asked whether or not we agree with it. After the renovation in 2000, and the context of a right wing politics in France and the plan vigipirate, changing the relationship with in and out the building, creating a glass wall, trying to have an audience… ‘is that what we wanted and who decided about it?’ she asks.

Today we should fight for freedom and accessibility to all, not just for the arts. Fighting for justice in the arts is fighting for justice in the world, and we could then reach a Fantastic Society.

During the Q&A with Alexander Roberts from Reykjavik Dance Festival, the question of equality of pay in the arts was raised, between artists and art workers. While Ganalopoulou explains her situation in Athens where the staff of MIR festival is all volunteers — even the director, but making a point for the artists to be paid, one questioned how to implement justice and equality even within the team.

To the question ‘are we inside or outside the system’, artist Sarah Vanhee argued that we are all in, whether or not we are an institution, whether or not we are pro or against it. Money flows, and a gig in Sweden may allow a gig in Greece to happen.

Marta Keil is a curator and researcher in Warsaw, Poland. Last year, after 5 years running a festival of international performing arts festival Konfrontacje Treatralne in Lublin with Grzegorz Reske, the city asked them to stop. To stop the activity. In a context of radical turn in the general politics towards the far right, the city that was originally supporting the festival, realised that the work done was trying to unveil the ways it was functioning and was criticizing it.

So the question is ‘how to work on a context’. How to recognize it. How to reproduce it (or not). How to pole a critical position.

Let’s try to show also other modes of the art system, and not reproduce the remaining model where one white middle class man comes with an idea, and an army of (art)workers make it happen.

Where the politics of a city is failing, and institutions are disappearing, or are getting more and more conservative, shall we fight against them? Keil expressed the struggle between willing to support and protect the art institutions but not be also sure these are the institution we want to protect… the example of the far right radicalisation of the art institutions in Poland raised the question of the politics of “not worst”: can we fight for an institution that is not full filing our ambitions but it’s “better than nothing”. If the remaining few art institutions were to disappear, not sure others would exist.

>> how can we work together: trying to reclaim it as a public institution… or find another space to do it ?

Mai Abu ElDahab

We need to think of the arts as an ecology.

How do we share responsibility and how do we not continue the long chain of reproduction of privilege?

Who has the right to speak about what?

Ask yourself what kind of institution do you defend. And defend institution by diversifying it.

In her presentation, Abu ElDahab took the example of the Arts Fellows, one of the support scheme existing at Mophradat: a paid traineeship in different art organisations in Europe, for Arab students. Supporting not only the artists, not only a programme, but mirroring your vision into your own structure is important.

The shift that needs to happen is in our power

To what Peggy Pierrot made a point to say that the heart of the problem of discrimination and privileges is about income and money: who can access money / who can move.

—————————————

Day #1 afternoon session – Questions raised around Take responsibility towards the context

by: Marine Thevenet

- How can institutions be the blueprint for the society?

- Being aware of where we are located

- Mirroring a better society: making a programme accessible to everyone in function of its accessibility.

- Bringing in diversity in the core of the institution, starting from board members or staff.

- What if all staff should change every 5 years?

- Question of power: how it is distributed in different ways.

- Collectiveness can be a way to bring in change

- Do we need a new institution or change the existing one ? opinions diverge on this question.

- Don’t estimate the power of politics made by art: the art create a symbolic that acts beyond the wall of the institution. Power to affect the society by creating / supporting forms of representation. Power of legitimization: example of Ahmet from The Silent University, who got hold of the policemen asking for his refugee status by showing his card with Tate logo on it…

- Cautious with the fantasy of doing something for everyone. Exemple of LIFT Tottenham: work with a dedicated community, in a dedicated area of London. Limit what you can do, and do it well.

- When do you become an institution? Maybe when you’re responsible for others than yourself?

—————————————

Day #2 – How to build a Fantastic Feminist Institution?

by: Delphine Hesters

Take care of the people inside your institution.

Taking care means recognizing them as full persons, not only as the slice which is the role they take up in your institution.

Make the way you organize your institution intersect with the lives of the people.

Model the way you work based on the most vulnerable person in your organization.

Take care of people and allow them to emancipate themselves through your institution.

Have lunch together. Eat healthy food.

Organize childcare for your staff.

Organize childcare for the audiences.

Organize childcare not to get rid of the problem called children, but find a way to incorporate the children into the institution.

Adjust the hours of work and presentations to the diverse schedules of the diverse people’s lives.

Develop a politics of listening. Make listening a core value. Listening to artists, colleagues, audiences, neighbors. Practice.

Having a politics of listening means not only scheduling time for listening when the organization sees it fit. It is about an attitude and about availability.

Begin every meeting with ‘checking in’. Allowing all present to talk about what they have on their minds, potential concerns that might be in the way.

Use oral communication.

Don’t use difficult words when they are not necessary.

Don’t underestimate the intelligence of the audience.

Do not think about the audience in terms of ‘the audience’, as a monolith.

Organize ‘relaxed performances’. (Google that).

If you have power, use it in order to give the voice to other people who usually don’t get a voice.

Be conscious about who is speaking on behalf of your intuition. Don’t speak in a singular voice.

Practice the ability to step aside.

Not all ‘problems’ have to be solved. Start with listening.

Practice, don’t promote. Show, don’t tell.

Take care of your physical environment together. Clean together.

Be transparent towards the people you work with (inside and outside) about your budget and its underlying logics.

Take responsibility for what happens with your money. (Are the artists on your stage paid well with the fee you paid for the show?)

If you invite someone for a meeting, organize to his or her convenience. Propose to go there, rather than invite them over.

If you invite a freelancer for a work meeting and you have a salary and decent funding: pay them a fee for the meeting.

Give credit.

Make work visible. Acknowledging the work done.

Establish long-term relationships with artists.

Invite the artists you build long-term relationships with to your board meetings.

Do not buy products from artists.

Don’t glorify the young and the new.

Trust.

Be kind.

(With thanks to the wonderful participants of the working group discussing what ‘a feminist institution’ could look like this afternoon.)

—————————————

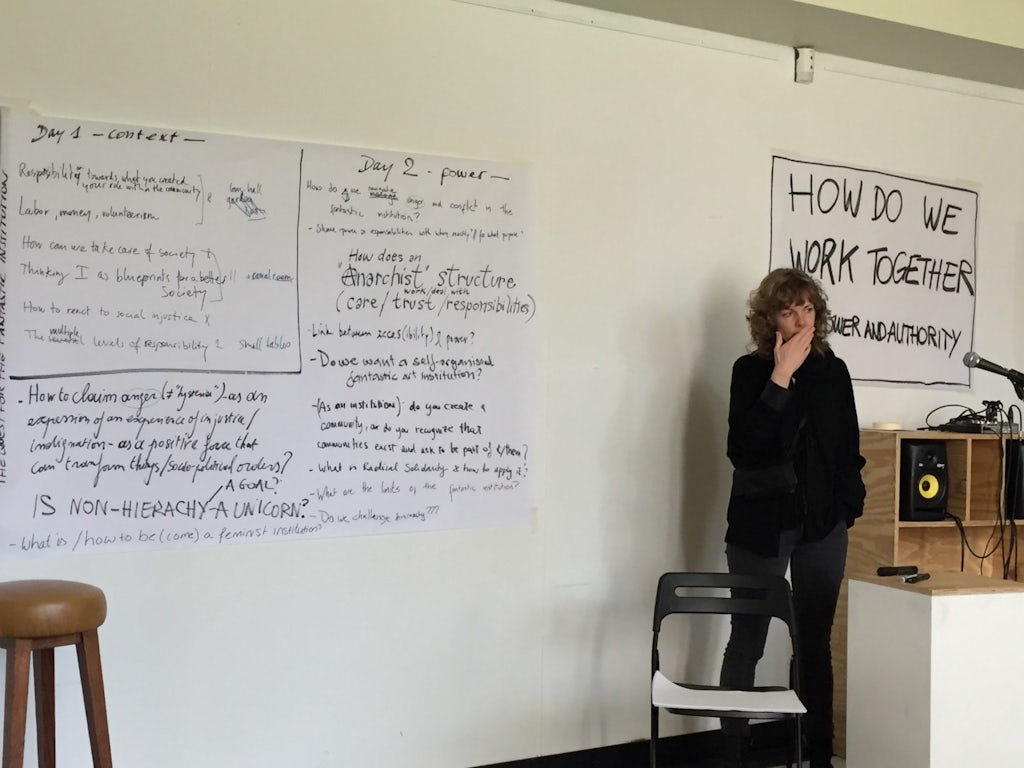

Day #2 – About power, authority and hierarchy

by Marine Thevenet

When it comes to working relationships with artists, with audience members, and with colleagues within the arts institutions, who is speaking? Who is making the decisions? How do we work together? The arts sector has been well recognised for its tendency to publicly display desires for radical socio-political change, and for addressing issues of power and authority, but without that so far leading to any visible effect in its own working. Should we simply conclude, once and all, that art institutions are simply reproducing the current power system without ever being able to affect it? Or are we able to take a closer look and identify places and ways where change is actually taking place?

Lecture by Georg Doecker

researcher at University of Giessen

Johan Forsman, Skogen

About self-organised school of Skogen, Gothenburg, that opened last October 2017.

25% of the total budget is put in the school, trying to respond to the questions:

> What else can be learnt together?

> How can a self-organised school be used by everyone?

> How common resources are linked to possible radicalism and solidarity?

> How to organize knowledge without turning resource into manageable

Examples of courses:

. newstherapy : newspaper reading group in the morning

. printing technology

. shift analogue to digital

. dancing on techno music in the morning

…

Forest Fringe is an organisation run collaboratively by three artists based in the UK. Together, they create festivals, host residencies and occasionally commission new work as a way of helping support a large and diverse community of independent artists working across and between theatre, dance and live art.

While presenting the 10 years of activity, taking about collectiveness, shared responsibility, independence, constant reinvention, diversity, question of passing the torch, how to mess about hierarchy, Andy Field cleverly shared his speech with his friends and colleagues Deborah Pearson and Ira Brand (and Brian Lobel) through the text itself. As he was reading it, his presentation was screened showing constant comments, revisions and additions by his peers. By the nature of this speech’s structure, Forest Fringe (via Field’s voice) managed not to talk about sharing power, but attempted to give up power within the essence itself of the performative lecture (see image). It also, within the lines, showed how easy is to take power over others, how one’s voice can be heard more if you don’t take into account the voice of the others.

It felt like a real achievement of take on action, instead of commenting them. And joined there the point Peggy Pierrot made, as an central element of the all day conversations: you need to take action in the system itself, and practice the values you defend.

Ilse Ghekiere

Artist Ilse Ghekiere presented on research and activism about sexism in the dance field: setting up a residency at Rosa, a feminist gallery. The question today, after the development of #makemovement and #wetoo, is how to broaden the conversation to other fields in the arts.

—————————————

Day #2 afternoon working group session – Bullet points around the question of HIERARCHY

by: Marine Thevenet

· Problem of accepting the vassality in a feudal relationship, and how can we do it otherwise.

· Bring fluidity and responsiveness

· Defining responsibilities

· Has to do with the content, not the organisation

· Should institutions work with mandates? in order to have the power and sense of hierarchy moving around ?

· Constant process of becoming: ask yourself ‘are we still needed ?’

· Not always a problem of hierarchy but how it is practiced

· Playing around with hierarchy and installed system: existence and acceptance of an ecology : self organisations / artists can be an answer to hierarchical system

· Good leadership brings in prospective, but shall we change the word ‘leadership’ ?

· Good to discussed what’s achieved as a group, and how you share and define responsibilities, which might involves also multiple hierarchies operating at the same time.

· How to take care of the content becoming and the problem when institutions become too institutionalized.

· Hierarchies in the larger ecology : self organisations / artists operating together, and experimenting new ways of shifting the power and the hierarchy of power.

· Leadership: easier to define leadership we don’t not want and we need to name and invent the leadership we want — and maybe it’s not ‘leadership’, and we need to invent a new vocabulary. The idea of having a voice in the society is really important. Fictional leaders.

· Responsiveness: should not be fixed.

· Responsiveness to the outside world, to the community

· Ecology: projects, institutions, organisations: create a unity around that, and it shouldn’t be monolithic. So you shouldn’t need only one institution, but a multitude of different smaller ones, combination of many approaches and diversities. So we are not talking about just a Fantastic Institution but also a Fantastic eco system, or a fantastic ecology.

—————————————

Day #3 – About (not) shutting up and listening

by Delphine Hesters

Day 3 of the Return of the Fantastic Institution has the lead question “How do we define the content of our institutions?” As Daniel Blanga Gubbay introduced the Saturday meetings: usually institutions know well what they do, but would be less specific about what they don’t do. Or, more precisely, about where the limit lies of what they are dealing with. This question is closely connected with the one about ‘who is in and who is out’. Saturday morning was filled with powerful observations, statements and stories – by Rachida Aziz of Le Space in Brussels, Anne Breure of Veem House for Performance in Amsterdam and Aaron Wright of Fierce Festival in Birmingham. They left one to think, not to speak. Therefore, what follows is a report of one of these presentations, with no need for much selection, reformulation or added commentary. (And a coda).

The story of Le Space – Rachida Aziz

If you want to ‘diversify’ your institution, you should decolonize yourself, change your own patterns. Self inspect. Recognize your own ignorance. Serve instead of command. Listen instead of speak. Come down instead of expecting that they climb your mountain.

(Ignorance lies in phrases such as “we are the organized sector, we should reach out to the unorganized sector.” Ignorance lies in only realizing that already a couple of hundred organizations suffered from razzias when the police is at your own doorstep.)

There are many practices of diversification in the cultural sector, which can have negative or devastating effects.

The risks of co-opting. Co-opting is moving talents from the margin into the mainstream. There are a lot of collectives, people who build a counter power, in a fine-grained network. What often happens with co-opting is talent drain. The collectives take the blow and become more fragile than before. The co-opted artist gets isolated, while meeting with big expectations — that s/he would be able to open doors, will change the system from within etc. Which often leads to burn-out, disenchantment or a sense of betrayal.

Transfering problems from margin to mainstream. Moving people from the margins to the mainstream means transferring their problems from margin to mainstream. However, as institutions are mostly unaware of the realities these often fragile individuals come from, and are themselves operating in highly competitive logics, they are not safe environment, no environments for proper care.

Tokenism. The mechanism of tokenism works as follows: if you are part of a disadvantaged group, you are seen as a specimen of that group. What you say or do will always reflects on the other specimens of that group. In this logics, one person of color on a panel is enough, because s/he is representative for the others of the larger group.

Tokenism combines well with the celebration or the idea of ‘embracing diversity’ by adopting the superficial ‘multicultural’ approach, where people are ethicized, boxed in the category of the country of their grandparents. Another problematic approach at the other end is the one of simplified hybridity, where everyone is considered the combination of many different identities, erasing any recognition of power differences and discriminations.

Setting up projects to diversify, reaching for additional funds, and as a result draining funds away from the underground that actually needs it more.

What Le Space does is trying to be a negation of those practices.

Making a public has been the largest ‘production’ of Le Space. It makes no distinction between the artistic crew and the people working on ‘audience development’. It is seen as a symbiosis. Only 5 to 10% of the programming in Le Space is done by the crew. And this core group already consists of 20 different people. The rest is done by the large network. Also the way in which artists are put on stage offers people in the audience the idea that being an artist is not just for a special group of people. It could be something for them too. What happens in this context is the creation of new artistic expressions, based on the reality of people who have direct needs of expression. New formats that don’t fit in any of the pre-existing boxes.

Offer mental coaching. As Le Space works with marginalized and precarious people, who grow up in a hostile environment and who have to deal with traumas, the artists active in Le Space get mental coaching. This takes a lot of very close mentorship and accompanying the artists on a daily basis.

Constantly developing new strategies, moving between practice and theory and back. Le Space changes according to context, all the time, because the context changes so quickly. The way the larger, older institutions are being run has been defined decades ago, while society has changed drastically. It is impossible to define five years in advance what will be produced in Le Space and how it will be done. It is not only impossible, it is also unfavorable.

Constantly repairing fractures between different disadvantaged groups (think illness, gender, sexuality, race, class…). These fractures or segregation are nurtured in society; disadvantaged groups are set up against each other. Dealing with this, bringing people together across those fractures is hard work on a daily basis. It is about understanding the strategies with which these people are set up against each other, making people from marginalized groups realize how the oppression works and making them realize that they actually support the oppressive system when they fight against each other.

“It is too late to rely on the institutions operating with white people’s strategies to achieve the change we need. The gap between consciousness and practice is too big. The strategies in place now will only allow us to reach gender equality in 500 years. The same with racial discrimination, the ecological reality. As if we have the time!” “I am standing on the side where the suffering, misery, hunger and humiliation is a very real, daily reality. We don’t have time,” Rachida Aziz says. “The people leading the institutions are usually the ones who are the last one in line to receive the violence. (But they will receive it. They tend to believe that the system is there for them, but is not true. If you are not the 1%, it will come for you as well.)”

“Within Le Space, a lot of white people are active. But what we do is ‘post-’ the ancient system of patriarchy, racism. The men in the organization need to understand that they have to deconstruct themselves as the norm. We don’t speak anymore of ‘people who are white or black’, but ‘people who believe they are white’ and ‘people who believe they are black.’”

As closing lecture of The Return of the Fantastic Institution, the wonderful Francis McKee of CCA Glasgow read his ‘The Rainbow Wrasse’, a short story that questions the future of art, institutions and artefacts in a future where climate change and its wide-ranging impact on societies and their infrastructure is resetting all our relationships.

He shared with us his believe in the power of fiction. “I am so fed up with theory. It is predictable and often has nothing to do with practice. In fiction, it is possible to speculate, to think through small steps and see what happens.” Writing a fictional story also was a strong exercise in empathy. “Me, an old white male trying to get into the head of two female characters, one actually being non-binary. It is hard-hard work. It is an attempt to respond to what we have been discussing these three days. It is not just a matter of shutting up.”